William Gilbert (physicist)

[3] After gaining his MD from Cambridge in 1569, and a short spell as bursar of St John's College, he left to practice medicine in London, and he travelled on the continent.

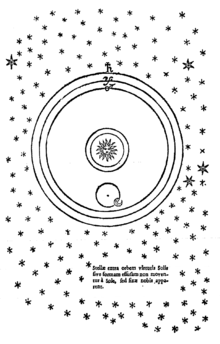

He states that, situated "in thinnest aether, or in the most subtle fifth essence, or in vacuity – how shall the stars keep their places in the mighty swirl of these enormous spheres composed of a substance of which no one knows aught?"

[11] Besides Gilbert's De Magnete, there appeared at Amsterdam in 1651 a quarto volume of 316 pages entitled De Mundo Nostro Sublunari Philosophia Nova (New Philosophy about our Sublunary World), edited – some say by his brother William Gilbert Junior, and others say, by the eminent English scholar and critic John Gruter – from two manuscripts found in the library of Sir William Boswell.

According to John Davy, "this work of Gilbert's, which is so little known, is a very remarkable one both in style and matter; and there is a vigor and energy of expression belonging to it very suitable to its originality.

In the opinion of Prof. John Robison, De Mundo consists of an attempt to establish a new system of natural philosophy upon the ruins of the Aristotelian doctrine.

[13] Gilbert died in 1603, and in his posthumous work (De Mundo nostro Sublunari Philosophia nova, 1631) we have already a more distinct statement of the attraction of one body by another.

[18] Francis Bacon never accepted Copernican heliocentrism, and was critical of Gilbert's philosophical work in support of the diurnal motion of Earth.

Historian Henry Hallam wrote of Gilbert in his Introduction to the Literature of Europe in the Fifteenth, Sixteenth, and Seventeenth Centuries (1848):[22] The year 1600 was the first in which England produced a remarkable work in physical science; but this was one sufficient to raise a lasting reputation to its author.

Gilbert, a physician, in his Latin treatise on the magnet, not only collected all the knowledge which others had possessed on that subject, but became at once the father of experimental philosophy in this island, and by a singular felicity and acuteness of genius, the founder of theories which have been revived after the lapse of ages, and are almost universally received into the creed of the science.

The magnetism of the earth itself, his own original hypothesis, nova illa nostra et inaudita de tellure sententia [our new and unprecedented view of the planet]... was by no means one of those vague conjectures that are sometimes unduly applauded...

...Gilbert was also one of our earliest Copernicans, at least as to the rotation of the earth; and with his usual sagacity inferred, before the invention of the telescope, that there are a multitude of fixed stars beyond the reach of our vision.

This so-called philosophical method was, in fact, very generally applied, and Kepler, who shared Galileo’s admiration for Gilbert’s work, adopted it in his own attempt to extend the idea of magnetic attraction to the planets.