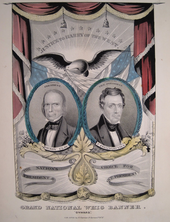

William Henry Harrison 1840 presidential campaign

Harrison, who had served as a general and as United States Senator from Ohio, defeated the incumbent president, Democrat Martin Van Buren, in a campaign that broke new ground in American politics.

A month after taking office, Harrison died and his running mate John Tyler served the remainder of his term, but broke from the Whig agenda, and was expelled from the party.

After a decade as governor of Indiana Territory, Harrison made his reputation fighting the Native Americans, notably at the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe and, once the War of 1812 began, the British.

Harrison rallies grew to unprecedented size, and the candidate delivered speeches at some of them, breaking the usual custom that the office should seek the man and presidential hopefuls should not campaign.

Harrison was sent to Hampden-Sydney College in 1787, where he developed a lifelong interest in Roman history, and then to Philadelphia to learn medicine from Dr. Benjamin Rush,[2] including study at the University of Pennsylvania.

Harrison remained in the West (resigning as governor to accept a military commission in 1812), but was unable to make much headway against the alliance due to British naval superiority on Lake Erie.

[12][13] Harrison wrote a letter to the newspapers that won over many Whigs, assuring them of his fidelity to party principles, such as the limited power of the executive and federal subsidies for roads, canals and railroads.

Former senator John Tyler of Virginia, a onetime Democrat who had broken with Jackson over states' rights, had been a regional Whig candidate for vice president in 1836, and had supported Clay at the convention.

The magnanimous tone of the letter contrasted with Clay's reaction when on December 8, the day after the convention closed, he became the first Whig presidential hopeful to learn the outcome: "My [political] friends are not worth the powder and shot it would take to kill them.

The origins of how this came to be are uncertain, though the most commonly rendered version of events has, in January 1840, Pennsylvania Whig operative Thomas Elder coming up with the idea of making log cabins a symbol of the Harrison/Tyler campaign.

[33] Robert Gray Gunderson, in his account of the 1840 election, described how one was displayed at a Harrisburg ratification meeting on January 20, and "within the month, cabins, [rac]coons, and cider became symbols of resurgent Whiggery.

Tens of thousands of delegates and spectators filled the streets as a mile-long parade featured log cabins on wheels, with the builders drinking hard cider on the roof, and giant wooden canoes with the image of Old Tippecanoe, though General Harrison was not in attendance.

This inspired a Harrison supporter from Zanesville, Ohio, Alexander Coffman Ross to write new lyrics to an old minstrel song called "Little Pigs", which immediately became a huge hit.

Greeley, by then editor of the widely circulated Harrison campaign journal, The Log Cabin, worried that the constant demands for money would drive the wealthy from politics; this did not occur.

Charles Ogle of Pennsylvania, a law student and political disciple of Thaddeus Stevens, utilized a debate on White House renovations to spend three days accusing Van Buren of living in luxury at considerable public expense:[45] "If he is vain enough to spend his money in the purchase of rubies for his neck, diamond rings for his fingers, Brussels lace for his breast, filet gloves for his hands, and fabrique de broderies de bougram à Nancy handkerchiefs for his pocket—if he chooses to lay out hundreds of dollars in supplying his toilet with 'Double Extract of Queen Victoria', Eau de Cologne, Corinthian Oil of Cream ... if, I say, Mr. Van Buren sees fit to spend his cash in buying these and other perfumes and cosmetics for his toilet, it can constitute no valid reason for charging the farmers, laborers and mechanics of this country with bills for HEMMING HIS DISH RAGS, FOR HIS LARDING NEEDLES, LIQUOR STANDS, AND FOREIGN CUT WINE COOLERS.

A subdued affair, it was greatly overshadowed by a huge "Whig Young Men" gathering that took place in Baltimore at the same time, featuring speeches by Senators Clay and Webster.

[53] As the log cabin theme took hold, alternative nicknames for Harrison such as "Old Buckeye" were dropped, and Whigs, heretofore more associated with the wealthier classes, sought to appeal to the humbly-born.

Harrison, however, felt the need to speak out and accepted an invitation to make an address at the June 13 commemoration of the 1813 Siege of Fort Meigs, where he and his troops had held out against British and Native American forces.

En route to Perrysburg, when leaving his hotel in Columbus, he made what Shafer called "the first presidential campaign speech in history", speaking to a small crowd of supporters, and defending his record against what he deemed personal attacks.

[59] Lines had been hardening on the matter of slavery, and Democrats accused Harrison of being an abolitionist because of his membership, a half century earlier, in the Richmond Humane Society, an anti-slavery group; he had posted a mixed record on the issue while in Congress.

[41] The economy continued to be poor in 1840, a fact the Whigs never ceased to press, arguing that Van Buren had done little and Harrison's inauguration was needed to put a stop to the hard times.

The aristocratic South Carolina former congressman, Hugh Legare also spoke widely, and took to wearing a coonskin cap on the campaign trail, drinking hard cider as he partied with the "Log Cabin Boys".

After making a hit in his first speech outside his home town at the February Columbus rally, the Whigs sent him on the road as a person who could appeal to the tradesmen and farmers who made up much of the electorate.

[67] The Democrats had seen the Whigs build log cabins, drink huge amounts of hard cider, hold outsized conventions and publish subsidized newspapers; they asked where the money was coming from to provide such expensive operations.

[70] On October 14, Jackson weighed in on the race, with a public letter published, "it is my serious belief that if General Harrison should be elected President it will tend to the destruction of our glorious Union and Republican system.

Twelve of the Van Buren electors did not vote for Johnson: eleven (all from South Carolina) chose Littleton W. Tazewell for vice president and one (from Virginia) favored Governor James K. Polk of Tennessee.

Noted New York Congressman Millard Fillmore, a future Whig president: "I understand they have come down upon General Harrison like a pack of famished wolves, and he has been literally driven from his CASTLE and forced to take refuge in Kentucky.

He made a very public progress from Ohio to Washington, getting little rest along the way: even those Whigs who were not seeking government employment wanted to see and meet the President-elect and celebrations often surrounded his hotel all night.

After consultation with Whig politicians, he filled his cabinet, to the disappointment of some, like Henry Clay, who saw his nominees passed over,[83] and Thaddeus Stevens, who believed he had been promised the position of Postmaster General.

[84] Harrison allowed Secretary of State-designate Daniel Webster to edit his inauguration speech, but he nevertheless spoke for an hour and 45 minutes, setting a record for verbosity that still stands.