William the Silent

A wealthy nobleman, William originally served the Habsburgs as a member of the court of Margaret of Parma, governor of the Spanish Netherlands.

William was born on 24 April 1533 at Dillenburg Castle in the County of Nassau-Dillenburg, in the Holy Roman Empire (now in Hesse, German Federal Republic).

In his testament, René of Chalon named William the heir to all his estates and titles, including that of Prince of Orange, on the condition that he receive a Roman Catholic education.

Besides the Principality of Orange (located today in France) and significant lands in Germany, William also inherited vast estates in the Low Countries (present-day Netherlands and Belgium) from his cousin.

William received his Catholic education in the Low Countries, first at his family's estate in Breda and later in Brussels under the supervision of the Emperor's sister Mary of Hungary, governor of the Habsburg Netherlands (Seventeen Provinces).

[7] It was in November of the same year (1555) that the gout-afflicted Emperor Charles leaned on William's shoulder during the ceremony when he abdicated the Low Countries in favour of his son, Philip II of Spain.

[5] In 1559, Philip II appointed William stadtholder (governor) of the provinces of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht, thereby greatly increasing his political power.

According to the Apology, William's letter of justification, which was published and read to the States General in December 1580, his resolve to expel the Spaniards from the Netherlands had originated when, in the summer of 1559, he and the Duke of Alba had been sent to France as hostages for the proper fulfilment of the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis following the Hispano-French war.

At the time, William did not contradict the king's assumption, but he had decided for himself that he would not allow the slaughter of "so many honourable people", especially in the Netherlands, for which he felt a strong compassion.

Philip made him councillor of state, knight of the Golden Fleece, and stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht, but there was a latent antagonism between the natures of the two men.

[5] But, in an iconic speech to the Council of State, William to the shock of his audience justified his conflict with Philip by saying that, even though he had decided for himself to keep to the Catholic faith (at the time), he could not agree that monarchs should rule over the souls of their subjects and take from them their freedom of belief and religion.

In late 1566, and early 1567, it became clear that she would not be allowed to fulfill her promises, and when several minor rebellions failed, many Calvinists and Lutherans fled the country.

He financed the Watergeuzen, refugee Protestants who formed bands of corsairs and raided the coastal cities of the Netherlands (often killing Spanish and Dutch alike).

Alba countered by killing a number of convicted noblemen (including the Counts of Egmont and Hoorn on 6 June), and then by leading an expedition to Groningen.

Their decisive victory in the Battle of Mookerheyde in the south east, on the Meuse embankment, on 14 April cost the lives of two of William's brothers, Louis and Henry.

While the new governor, Don Juan of Austria, was en route, William of Orange got most of the provinces and cities to sign the Pacification of Ghent, in which they declared themselves ready to fight for the expulsion of Spanish troops together.

When Don Juan signed the Perpetual Edict in February 1577, promising to comply with the conditions of the Pacification of Ghent, it seemed that the war had been decided in favour of the rebels.

On 6 January 1579, several southern provinces, unhappy with William's radical following, signed the Treaty of Arras, in which they agreed to accept their Catholic governor, Alessandro Farnese, Duke of Parma (who had succeeded Don Juan).

Because he had agreed to remove the Spanish troops from the provinces under the Treaty of Arras, and because Philip II needed them elsewhere subsequently, the Duke of Parma was unable to advance any further until the end of 1581.

In March 1580 Philip issued a royal ban of outlawry against the Prince of Orange, promising a reward of 25,000 crowns to any man who would succeed in killing him.

William responded with his Apology, a document (in fact written by Villiers) in which his course of actions was defended, the person of the Spanish king viciously attacked,[24] and his own Protestant allegiance restated.

The prince had already sought French assistance on several occasions, and this time he managed to gain the support of Francis, Duke of Anjou, brother of King Henry III of France.

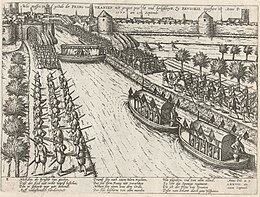

When Anjou's French troops arrived in late 1582, William's plan seemed to pay off, as even the Duke of Parma feared that the Dutch would now gain the upper hand.

His great-grandson William III and II, King of England, Scotland and Ireland, and Stadtholder in the Netherlands, was buried in Westminster Abbey.

However, as Philip William was a hostage in Spain and had been for most of his life, his brother Maurice of Nassau was appointed Stadholder and Captain-General at the suggestion of Johan van Oldenbarneveldt, and as a counterpoise to the Earl of Leicester.

So, Frederick Henry, Maurice's half-brother (and William's youngest son from his fourth marriage, to Louise de Coligny) inherited the title of Prince of Orange.

As the chief financer and political and military leader of the early years of the Dutch revolt, William is considered a national hero in the Netherlands, even though he was born in Germany, and usually spoke French.

His conscience, said the King, would not be easy nor his realm secure until he could see it purged of the "accursed vermin," who would one day overthrow his government, under the cover of religion, if they were allowed to get the upper hand.

The King talked on thus to Orange in the full conviction that he was aware of the secret agreement recently made with the Duke of Alba for the extirpation of heresy.

Besides being ruler over the principality of Orange and a Knight of the Golden Fleece, William possessed other estates, mostly enfeoffed to some other sovereign, either the King of France or the imperial Habsburgs.