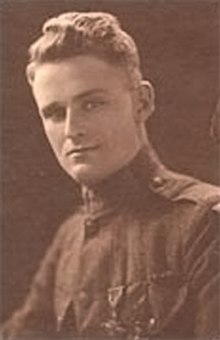

William March

His father worked as a "timber cruiser", estimating which stands of trees were big enough to warrant lumber companies investing in a saw mill in the area.

[4] His mother, whose maiden name was Susan March, was probably better educated and taught the children to read and write; in the eyes of her family, she had married beneath herself.

[5] Neither parent seemed to have supported young March's literary efforts; he later stated he had composed a 10,000 line poem at the age of 12 but had burned the manuscript.

There he lived in a small boarding house in Brooklyn, found work as a clerk in the Manhattan law firm of Nevins, Brett and Kellog, and attended plays.

[10] Along with two other future World War I literary figures, John W. Thomason and Laurence Stallings),[citation needed] March embarked on USS Von Steuben at Philadelphia.

As a member of the 5th Marines, March saw his first action on the old Verdun battlefield near Les Éparges and shortly afterwards at Belleau Wood, where he was wounded in the head and shoulder.

The next day, "during a counterattack, the enemy having advanced to within 300 meters of the first aid station, he immediately entered the engagement and though wounded refused to be evacuated until the Germans were thrown back".

An experience March told a number of times included his jumping into a bomb crater to take shelter and coming face to face with a young German soldier, whom he instantly bayoneted; this anecdote also found its way into Company K.[16] The official citation to the Croix de Guerre reads as follows: During the operations in Blanc Mont region, October 3–4, 1918, he left a shelter to rescue the wounded.

On October 5, during a counter-attack, the enemy having advanced to within 300 meters of the first aid station, he immediately entered the engagement and though wounded refused to be evacuated until the Germans were thrown back.

[citation needed] The aforementioned experience, of having bayoneted a young, blond German soldier, is recounted in Company K and is there attributed to Private Manuel Burt; March suffered hysterical attacks at different moments in his life related to the throat and the eyes.

Also in Hamburg he witnessed the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime and wrote a prophetic short story, "Personal Letter", which expressed anxiety over the political future of Germany and the world.

March was fearful of publishing the story, as he was already well-established as an anti-militarist author and was afraid to place his German friends and associates in undue peril.

[26] Psychological problems that had already bothered him in Germany worsened in London, and he became a patient of psychoanalyst Edward Glover, who was able to cure March's throat paralysis, diagnosing it as a hysterical condition.

[30] 1937, Simmonds notes, was an important year: it marked the high point of his productivity as a short-story writer, and the magazine The American Mercury took up Company K for a reprinting.

[31] In 1943, he completed his most ambitious and critically acclaimed novel, The Looking-Glass, the final book in his "Pearl County" series;[32] Bert Hitchcock, literature professor at Auburn, called it March's "finest literary achievement".

"[34] This critical acclaim notwithstanding, in 1947, after years of depression from his experiences in the war and a continuing bout of writer's block, March suffered a nervous breakdown.

March returned Perls' friendship with a steady acquisition of works by Soutine, Joseph Glasco, Picasso, and Georges Rouault.

[37] In late 1950, March permanently left Mobile and purchased a Creole cottage on Dumaine Street in the French Quarter of New Orleans.

March's novels are psychological character studies that intertwine his own personal torment—deriving presumably from childhood trauma as well as from his war experiences—with the conflicts spawned by class, family, sexual, and racial matters.

Company K, published in 1933, was hailed as a masterpiece by critics and writers alike and has often been compared to Erich Maria Remarque's classic anti-war novel All Quiet on the Western Front for its hopeless view of war.

University of Alabama professor of American literature and author Philip Beidler wrote, in his introduction to a republication of the book in 1989, that March's "act of writing Company K, in effect reliving his very painful memories, was itself an act of tremendous courage, equal to or greater than whatever it was that earned him the Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross and French Croix de Guerre.

"[53] The Bad Seed, published in April 1954, was a critical and commercial success, and introduced Rhoda Penmark, an eight-year-old sociopath and burgeoning serial killer.

[54] James Kelley writes, for The New York Times Book Review, "The Bad Seed scores a direct hit, either as exposition of a problem or as a work of art.

Referring to the author's repressed homosexuality, cultural historian Foster Hirsch opines that in this novel's "incendiary melodrama, March transferred his own hidden sexuality into the story of the bad seed...a child who kills and who has inherited her evil nature from her grandmother, a serial murderer."

Hirsch goes on to observe that March's story raises the question--in the mid-1950s: "is homosexuality determined at birth, or is it caused by environmental conditions such as an overbearing mother and an absent father?

The Filipino poet and critic José García Villa regarded March as "the greatest short story writer America has produced.

A little book with a March story, "The First Sunset", was printed in a limited edition of 150 copies by Cincinnati printer and writer Robert Lowry's Little Man Press.

[65] Although March had intimated that he wished for no biography to be written,[58] the Campbell family, after having read the completed manuscript, gave their approval, though grudgingly, it seems.

[66] The biography received positive reviews, with one reviewer calling it "a critical study that is a judicious record of March's life and a fine tribute to his literary achievement",[45] and closes on a note of praise: The cruel irony of his death, coming at the moment it did, deprived him of the immense satisfaction of the worldwide recognition he would have enjoyed following the success of The Bad Seed.

Those of us who know, love, and admire his work live in the belief that one day March will be recognized as one of the most remarkable, talented, and shamefully neglected writers that America has produced in this or in any other century.