William McKinley 1896 presidential campaign

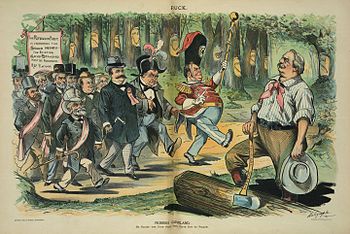

Hanna raised millions for a campaign of education with trainloads of pamphlets to convince the voters that free silver would be harmful, and once that had its effect, even more were printed on protectionism.

McKinley stayed at home in Canton, running a front porch campaign and reaching millions through newspaper coverage of the speeches he gave to organized groups of people.

[2] In the latter part of the 19th century, Ohio was deemed a crucial battleground state; taking its electoral votes was thought essential for a Republican to win the White House.

McKinley's tariff proved unpopular among many people who had to pay the increased prices, and was seen as a reason not only for his defeat for re-election to Congress in 1890, but also for the Republicans losing control of both House and Senate in that year's midterm elections.

Foraker's ambition then was the Senate—he planned to challenge Sherman in the legislative election to be held in January 1892[a]—and he agreed to nominate McKinley for governor at the state convention in Columbus.

[13] McKinley's name was not offered in nomination at the 1892 Republican National Convention, where he served as permanent chairman, but some delegates voted for him anyway, and he finished third behind Harrison (who won a first ballot victory) and Blaine.

President Harrison left office proclaiming the nation's prosperity, but in May, amid economic uncertainty that caused many people to convert assets into gold, the stock market crashed, and many firms went bankrupt.

Many Democrats, and some Republicans, felt that the gold standard limited economic growth, and supported bimetallism, making silver legal tender, as it had been until the passage of the Coinage Act of 1873.

Many farmers, faced with the long decline in agricultural prices that persisted through the first half of the 1890s, felt that bimetallism would expand the money supply and make it easier to pay their debts.

[23] Cleveland was a firm supporter of the gold standard, and believed the massive amounts of silver-backed currency issued pursuant to the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 had helped crash the economy.

Campaigning throughout the eastern half of the country on behalf of Republican candidates, and venturing even to New Orleans in the Democratic Solid South, McKinley spoke to large, enthusiastic crowds as often as 23 times in a day.

[29] At the time, unless there was an incumbent elected Republican president, the nomination was generally not decided until the convention, with state political bosses and delegates exacting a price for their support.

McKinley and Hanna decided on a systematic nationwide effort to gain the nomination, employing what onetime presidential adviser Karl Rove—author of a 2015 book on the 1896 race—called "the first modern primary campaign".

[b][30] To devote himself full-time to McKinley's presidential campaign, Hanna in 1895 turned over management of his companies to his brother Leonard, and rented a house in Thomasville, Georgia, expressing a dislike for Cleveland's winters.

[32] By the time he left Thomasville, he had gained the support of the majority of likely southern delegates;[33] Platt wrote mournfully in his autobiography that Hanna "had the South practically solid before some of us awakened".

[35] McKinley realized that it would be risky to have a faction hostile to the presidential candidate within his home state, and sought an alliance, campaigning for Bushnell and for a Republican legislature that would send Foraker to Washington.

He returned to report that the bosses were willing to assure McKinley's nomination in exchange for a pledge to give them control over patronage in their states and a promise in writing that Platt would be Treasury Secretary.

[53] As McKinley awaited his opponent, he privately commented on the nationwide debate over silver, stating to his Canton crony, Judge William R. Day, "This money matter is unduly prominent.

The final speaker during the debate on the platform was former congressman Bryan, who with Dawes in the gallery delivered a speech decrying the gold standard that to Democrats, according to Phillips, was "messianic—a call to arms".

[57] Dawes deemed his friend's Cross of Gold speech magnificent, though with "pitiably weak" logic, but it won Bryan the presidential nomination, and Phillips noted that the address "unnerved Midwestern Republicans, mindful of their own distrust of the East, and threw a weighty stone into the quiet pool of June GOP electoral assumptions".

The Republicans were caught by surprise by the wave of enthusiasm that Bryan's speech and nomination caused, and scuttled these plans; as Hanna wrote to McKinley on July 16, "the Chicago convention has changed everything".

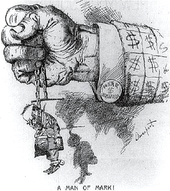

[60] Hanna quickly realized that the currency issue struck an emotional chord in many Americans, and decided on a campaign to persuade the voter that "sound money", the gold standard unless modified by international agreement, was much preferable to bimetallism.

Such propaganda would not be cheap, as before the age of television and radio, the most effective way of reaching the electorate was through the written word, and through public speakers who would address meetings on behalf of the candidate.

He faced resistance at first, both because he was not yet widely known on the national scene, and because some moneymen, although appalled at the Democratic position on the currency issue, felt Bryan was so extreme that McKinley was sure to win.

Reports of Bryan support in the crucial Midwest, and intervention by Hanna's old schoolmate, John D. Rockefeller (his Standard Oil gave $250,000), made executives more willing to listen.

A popular source of keepsakes was the wood of McKinley's front porch or fence, whittled as supporters listened, and the blades of his lawn, when not trampled underfoot, made later appearances in scrapbooks.

In between delegations, McKinley entertained visitors; future Secretary of State John Hay, a major backer, came to Canton reluctantly, not relishing the crowds, but wrote "he met me at the [railroad] station, gave me meat & took me upstairs and talked for two hours as calmly & serenely as if we were summer boarders in Bethlehem, at a loss for means to kill time.

[83] McKinley, on the urgent advice of his advisers, by the middle of that month had decided that the currency question must be addressed immediately, and the campaign machine began the process of generating millions of publications and sending hundreds of speakers into the field.

[84] Theodore Roosevelt, then a member of the New York City Police Commission, recalled seeing boxcars full of paper being dispatched when he visited the Chicago headquarters in August.

He helped to run the New York office, gave some speeches from his own front porch in Paterson, and in October went on a short campaign tour of New Jersey, though he was a reluctant public speaker.