William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

From an early age O'Brien's political ideas, like most of his contemporaries, were shaped by the Fenian movement and the plight of the Irish tenant farmers, his elder brother having participated in the rebellion of 1867.

It resulted in O'Brien himself becoming actively involved with the Fenian brotherhood, resigning in the mid-1870s, because of what he described in 'Evening Memories' (p. 443–4) as "the gloom of inevitable failure and horrible punishment inseparable from any attempt at separation by force of arms".

With this action, he first displayed his belief that only through parliamentary reform and with the new power of the press that public opinion could be influenced to pursue Irish issues constitutionally through open political activity and the ballot box.

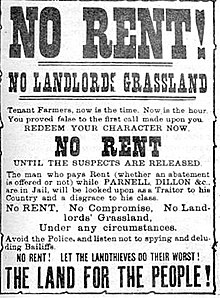

[3] In 1887 O'Brien helped to organise a rent strike with John Mandeville during the Plan of Campaign at the estate of Lady Kingston near Mitchelstown, County Cork.

On 9 September, after an 8,000-strong demonstration led by John Dillon MP, three estate tenants were shot dead, and others wounded, by police at the town's courthouse where O'Brien had been brought for trial with Mandeville on charges of incitement under a new Coercion Act.

Later that year, thousands of demonstrators marched in London to demand his release from prison and clashed with police at Trafalgar Square on Bloody Sunday (13 November).

[7] After six sittings all eight tenants' demands were conceded (one with compromise),[8] O’Brien having guided the official nationalist movement into endorsement of a new policy of "conference plus business".

[11] Together with Thomas Sexton editor of the party's Freeman's Journal, all three campaigned against O’Brien, fiercely attacking him for putting Land Purchase and Conciliation before Home Rule.

Declaring that he was making no headway with his policy, he resigned his Parliamentary seat in November 1903, closed down his paper the Irish People and left the party for the next five years.

During 1904 O'Brien had already embarked on advancing full-scale implementation of the Act in alliance with D. D. Sheehan MP and his Irish Land and Labour Association (ILLA) when they formed the Cork Advisory Committee to help tenants in their negotiations.

Determined to destroy both of them "before they poison the whole country",[15] Dillon and the party published regular denunciations in the Freeman's Journal, then coupéd O'Brien's UIL with the appointment of its new secretary, Dillon's chief lieutenant, Joseph Devlin MP, Grandmaster of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, Devlin eventually gaining organisational control over the entire UIL and IPP organisations.

O'Brien had in the meantime engaged with the Irish Reform Association, together with Sir Anthony MacDonnell, a Mayo Catholic originally appointed by Wyndham, and head of the Civil Service in Dublin Castle, anxious to do something for Ireland.

The next issue was to provide extensive rural housing for the tens of thousands of migrant farm labourers struggling to survive in stone cabins, barns or mud hovels.

[24] The labourer-owned cottages erected by the Local County Councils brought about a major socio-economic transformation, by simultaneously erasing the previous inhuman habitations.

The programme financed and produced during the course of the next five years, the erection of over 40,000 working-class cottages, each on an acre of land, a complete 'municipalisation' of commodious dwellings dotting the rural Irish countryside.

This unique social housing programme unparalleled anywhere else in Europe brought about an unsurpassed agrarian revolution, changing the face of the Irish landscape, much to O'Brien's expressed delight.

[23] Renewed publication of O'Brien's newspaper The Irish People (1905–1909) exalting the cottage building, its editorials equally countermanding the IPPs' "Dublin bosses" attempts to curtail the programme, fearing settled rural communities would no longer be dependent on Party and Church.

O’Brien saw it opportune for a cooperative understanding with Arthur Griffith's moderate Sinn Féin movement, having in common – attaining objectives through "moral protest" – political resistance and agitation rather than militant physical-force.

[32] On 2 November 1911 O'Brien proposed full Dominion status similar to that enjoyed by Canada, in an exchange of views with Asquith,[33] as the only viable solution to the "Irish Question".

During the 1913–14 Parliamentary debates on the Third Home Rule Bill, O'Brien, alarmed by Unionist resistance to the bill, opposed the IPP's coercive "Ulster must follow" policy, and published in the Cork Free Press end of January 1914 specific concession, including a suspensory veto right,[34] which would enable Ulster join a Dublin Parliament "any price for an United Ireland, but never partition".

William O'Brien resigned his seat as MP again for a fourth time in January and re-stood to test local support for his policies after the All-for-Ireland League suffered heavy defeats in the Cork City municipal elections.

Towards the end of August, he had an interview with Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State for War, and laid before him a scheme for raising an Irish Army Corps embracing all classes and creeds, South and North.

And in fighting England's battle in the particular circumstance of this war, I am convinced to the heart's core that we are fighting the most effective battle in all the ages for Ireland's liberty (cheers) as well as to save our towns and our homes and our women and children from the grip of the most appalling horde of brutes in human shape that ever cursed this earth since Atilla met his doom at the hands of eternal justice (cheers).

[41]O'Brien later wrote: "Whether Home Rule is to have a future will depend upon the extent to which the Nationalists in combination with Ulster Covenanters, do their part in the firing line on the fields of France".

[42] He stood on recruiting platforms with the other National leaders and spoke out encouragingly in favour of voluntary enlistment in the Royal Munster Fusiliers and other Irish regiments.

During the anti-conscription crisis in April 1918 O'Brien and his AFIL left the House of Commons and joined Sinn Féin and other prominentaries in the mass protests in Dublin.

He and the other members of his All-for-Ireland League party stood aside putting their seats at the disposal of Sinn Féin, whose candidates returned unopposed in the December 1918 general elections.

"[46]O'Brien disagreed with the establishment of a southern Irish Free State under the Treaty, still believing that Partition of Ireland was too high a price to pay for partial independence.

"[47] Retiring from political life, he contented himself with writing and declined Éamon de Valera's offer to stand for Fianna Fáil in the 1927 general election.

These are: Patrick Guiney ( North Cork ), James Gilhooly ( West Cork ), Maurice Healy ( North-east Cork ), D. D. Sheehan ( Mid Cork ), and Eugene Crean ( South-east Cork ).

The other MPs elected in January 1910 were: William O'Brien ( Cork city ), John O'Donnell ( South Mayo ) and Timothy Michael Healy ( North Louth ).