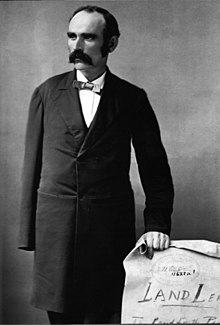

Michael Davitt

Davitt travelled widely, giving lectures around the world, supported himself through journalism, and served as Member of Parliament (MP) for the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) during the 1890s.

His Georgist views on the land question put him on the left wing of Irish nationalism, and he was a vociferous advocate of alliance between the Radical faction of the Liberal Party and the IPP.

[3] In 1868, he left Cockcroft's printing firm to work full-time for the IRB, as an organising secretary and arms agent for England and Scotland, posing as a travelling salesman as cover.

[1] Imprisoned at Millbank, Dartmoor, and Portsmouth,[1] Davitt was held for months in solitary confinement and endured hard labour and poor rations that permanently damaged his health.

In July 1878, Davitt made a trip to visit them and raise money through a lecture tour to bring his mother and youngest sister back to Ireland (his father had since died).

[8] In meetings with Irish-American Fenians, Davitt developed the strategy called the "New Departure", an informal collaboration between the physical force and parliamentary wings of Irish nationalism focusing on the land reform campaign.

[10][11] This collaboration was cemented during a meeting on 1 June 1879 in Dublin between Davitt, Devoy, and Charles Stewart Parnell, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), which advocated Home Rule achieved via Parliament.

[12][a] Agrarian unrest in the west of Ireland was sparked by the 1879 famine, a combination of heavy rains, poor yields and low prices that brought widespread hunger and deprivation.

[17] In May 1880, following Parnell's tour of the United States, Davitt travelled there to raise funds for the Land League,[18] specifically for political action to free Irish peasants "from the humiliation of a beggar's position".

For the thirteen weeks that Davitt was in the United States, he and Lawrence Walsh were effectively the only national leaders; they worked closely with Anna Parnell, who provided assistance.

[25] In April, the government introduced the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881, which Liberal minister Joseph Chamberlain described as removing "the chief grievance" of the agitators by granting many of their demands:[28] fair rent, free sale, and fixity of tenure.

[1] He also read many liberal thinkers, such as John Stuart Mill, Adolphe Thiers, Augustin Thierry, François Guizot, William Edward Hartpole Lecky, and Thomas Babington Macaulay.

Davitt worked closely with John Ferguson, the Irish leader in Glasgow who had been involved in the Crofters' War agitation by Highland tenant farmers in the early 1880s and later in the Irish-Radical political alliance that was the forerunner of the Scottish Labour Party.

Although it was initially a success and sold 60,000 copies of its second edition, the Labour World stopped publishing the following year due to Davitt's illness, lack of funds, and other problems.

He stood unopposed for North East Cork at a by-election in February 1893, making his maiden speech in favour of the Home Rule Bill in April, which passed the House of Commons but was defeated in the Lords in September.

[57] The trip resulted in his second book, Life and Progress in Australasia (1896), with particular attention to governance and the situation of minorities such as Indigenous Australians and the Kanakas, Pacific Islanders brought in to work at very poor conditions in the colonies.

[63] Obtaining commissions from William Randolph Hearst's New York American and the Irish paper Freeman's Journal, he travelled to South Africa to report on the war and lend support to the Boer cause.

Later in 1906, after the Liberal Party came to power, his open support for their policy of state control of schooling, rather than denominational education, merged into a conflict between Davitt and the Catholic Church.

[70] Davitt's estate was valued at £151;[1] in his will, he wrote "To all my friends I leave kind thoughts, to my enemies the fullest possible forgiveness and to Ireland the undying prayer for absolute freedom and independence, which it was my life's ambition to try and obtain for her.

Davitt foresaw that public funds spent on land purchases would never benefit landless labourers, and believed that the resulting smallholdings would eventually be consolidated into estates.

For example, his 1878 manifesto had three main planks, the right to bear arms, self-government, and land reform to bring about "a system of small proprietorship similar to what at present obtains in France, Belgium, and Prussia".

[82] According to English historian Michael Kelly, Davitt's public renunciation of political violence made him "the Irish Republican Brotherhood's greatest apostate".

[92][93] In 1898 at a meeting in Tonypandy, Davitt launched what Biagini (2007) called an "anti-Semitic tirade" against George Goschen, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, arguing that he "represented that class of bond-holders, and usurers, and mostly money-lenders for whom that infamous Egyptian war was waged".

[95][96] While opposing "cowardly racial warfare" such as the Kishinev pogrom, Davitt announced that he was "resolutely in line with... [the] spirit and programme" of antisemitism when it stood "against the engineers of a sordid war in South Africa, or as the assailant of the economic evils of unscrupulous capitalism anywhere".

[98] According to Stanford University historian Steven Zipperstein, Davitt "emerged as a folk hero among Jews" following his writings on Kishinev, with plays written about him in English and Yiddish.

[100] Political scientist Eugenio Biagini views Davitt as "a social radical in the Tom Paine tradition" who was the "chief inspirer of the Land League and the greatest hero of popular nationalism".

[101] Freeman's Journal lead writer James Winder Good hailed Davitt as the man whose "hammer strokes destroyed a system of land tenure, which for over three centuries had been the most powerful instrument in encompassing the economic degradation of the Irish people, and ensuring their subjugation to alien rule.

"[102] James Connolly considered Davitt "an unselfish idealist, who in his enthusiasm for a cause gave his name, and his services freely at the beck and call of men who despised his ideals".

[83] Moody wrote that Davitt's habit of "reinterpreting his past actions and attitudes in accordance with altered conditions was partly the outcome of a longing for integrity in his political conduct".

[108] In his obituary, The Times wrote that, "Anything more misleading than his presentation of what he calls The Boer Fight for Freedom cannot be imagined, unless it be his still wilder travesty of history, grotesquely named The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland.