Willie Mays

In 1954, he won the NL Most Valuable Player (MVP) Award, leading the Giants to their last World Series title before their move to the West Coast.

[11] Cat exposed Willie to baseball at an early age, playing catch with him at five and allowing him to sit on the bench with his Birmingham Industrial League team at ten.

[16] Mays's professional baseball career began in 1948 when he played briefly during the summer with the Chattanooga Choo-Choos, a Negro minor league team.

[23] Mays spent the rest of 1950 with the Class B Trenton Giants of the Interstate League, batting .353 with 20 doubles, eight triples, four home runs and 55 RBI in 81 games.

Although his .274 average, 68 RBIs, and 20 home runs (in 121 games) would rank among the lowest totals of his career, he still won the National League (NL) Rookie of the Year Award.

Mays was in the on-deck circle on October 3 when Bobby Thomson hit a three-run homer to win the three-game NL tie-breaker series 2–1.

Mays' time playing for the Wheels ended on July 28, 1953, after he chipped a bone in his left foot while sliding into third base, necessitating a six-week stint in a cast.

[66] The 1954 series is perhaps best remembered for "The Catch", an over-the-shoulder running grab by Mays of a long drive off the bat of Vic Wertz about 425 feet (130 m) from home plate at the Polo Grounds during the eighth inning of Game 1.

In the game against the Phillies, Mays reached second base on an error, stole third, and scored the winning run on a Hank Sauer single, all on plays close enough that he had to slide to make each one.

[98][99] "I don't like to talk about 1960," Mays said after the final game of a season in which the Giants, pre-season favorites for the pennant, finished fifth out of eight NL teams.

[107][108] Whatever the reason, the boos, which had begun to subside after Mays's four–home-run game in 1961, grew even quieter in 1962, as the Giants enjoyed their best season since moving to San Francisco.

[111] On September 30, Mays hit a game-winning home run in the Giants' final regularly scheduled game of the year, forcing the team into a tie for first place with the Los Angeles Dodgers.

On a close play, umpire Tony Venzon initially ruled him out, then changed the call when he saw Roseboro had dropped the ball after Mays collided with him.

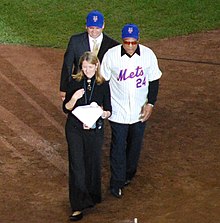

[170][171] Mays had remained popular in New York, and owner Joan Payson had long wanted to bring him back to his major league roots.

[174] Things did not improve as the season began; Mays spent time on the disabled list early in the year and left the park before a game when he found out Berra had not put his name in the starting lineup.

His speed and powerful arm in the outfield, assets throughout his career, were diminished in 1973, and he only made the All-Star team because of a special intervention by NL President Chub Feeney.

"I thought I'd be crying by now," he told reporters and Mets' executives at a press conference that day, "but I see so many people here who are my friends, I can't...Baseball and me, we had what you might call a love affair.

[180] Game 5 was the only one Mays played; he had a pinch-hit RBI single as the Mets won 7–2, clinching a trip to the 1973 World Series against the Oakland Athletics, October 13–21.

[191] At Cleveland Stadium in the 1963 All-Star Game, he made the finest catch, snagging his foot under a wire fence in center field as he grasped a long fly ball hit by Joe Pepitone that might have given the AL the lead.

Following his rookie year, Mays went on a barnstorming tour with an All-Star team assembled by Campanella, playing in Negro League stadiums around the southern United States.

"[203] His focus extended to his antics, or lack thereof, at the plate; Mays did not rub dirt on his hands or stroll around the batter's box like some hitters did.

[204] Naturally more of a pull hitter, Mays adjusted his style in 1954 to hit more to right and center field in a quest for a higher batting average at his manager's request, but the change was not permanent.

[210] Referring to the other 23 voters, New York Daily News columnist Dick Young wrote, "If Jesus Christ were to show up with his old baseball glove, some guys wouldn't vote for him.

"[85] At the Pittsburgh drug trials in 1985, former Mets teammate John Milner testified Mays kept a bottle of liquid amphetamine in his locker at Shea Stadium.

[236] Unlike other black athletes such as Jackie Robinson, Mays tended to remain silent on racial issues, refraining from public complaints about discriminatory practices that affected him.

Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and Mays's lawyer intervened, and the Mets agreed to keep him, as long as he stayed at home games for at least four innings.

[272] Another well-known song which mentions Mays is "Talkin' Baseball (Willie, Mickey & The Duke)" by Terry Cashman (1981), which refers to the three great New York City center fielders of the 1950s.

[283] However, James S. Hirsch wrote in The New York Times in 2021, on the occasion of his 90th birthday, that his vision was merely "compromised" by glaucoma and that he was still able to watch games on television, albeit with difficulty.

[287][288] The day before, he had released his final public statement when he said he chose to stay in California and not attend the MLB at Rickwood Field game between the Giants and Cardinals later that week on June 20.

A number of Mays' former teammates attended the ceremony, and among the speakers were baseball commissioner Rob Manfred, former presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, and former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown.