Presidency of Woodrow Wilson

[21] Wilson fervently believed that public opinion ought to shape national policy, albeit with a few exceptions involving delicate diplomacy, and he paid close attention to newspapers.

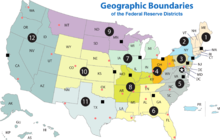

[30] The Democrats had four major priorities: the conservation of natural resources, banking reform, tariff reduction, and equal access to raw materials, which was accomplished in part through the regulation of trusts.

[33] Wilson argued that the system of high tariffs "cuts us off from our proper part in the commerce of the world, violates the just principles of taxation, and makes the government a facile instrument in the hands of private interests.

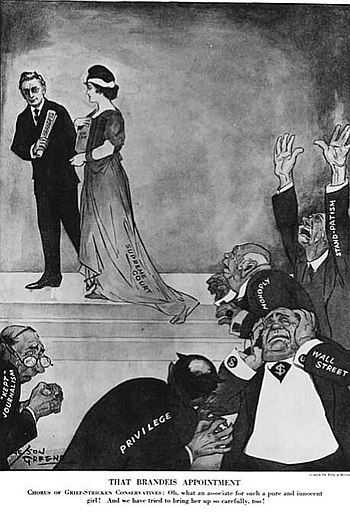

[57] With Wilson's support, Congressman Henry Clayton, Jr. introduced a bill that would ban several anti-competitive practices such discriminatory pricing, tying, exclusive dealing, and interlocking directorates.

At the Governor of Colorado's request, the Wilson administration sent in troops to end the dispute, but mediation efforts failed after the union called off the strike due to a lack of funds.

The final phases of the Philippine–American War were still ongoing during the first several months of Wilson's presidency, with the American victory at the Battle of Bud Bagsak in June 1913 bringing an end to nearly 15 years of anti-American resistance on the islands.

He set up divisions in his new agency to produce and distribute innumerable copies of posters, pamphlets, newspaper releases, magazine advertisements, films, school campaigns, and the speeches of the Four Minute Men.

[118] Anarchists, Industrial Workers of the World members, and other antiwar groups attempting to sabotage the war effort were targeted by the Department of Justice; many of their leaders were arrested for incitement to violence, espionage, or sedition.

[122] A combination of the temperance movement, hatred of everything German (including beer and saloons), and activism by churches and women led to ratification of an amendment to achieve Prohibition in the United States.

He did not speak publicly on the issue except to echo the Democratic Party position that suffrage was a state matter, primarily because of strong opposition in the white South to Black voting rights.

[128] That same year, Wilson appointed Helen H. Gardener to a seat on the United States Civil Service Commission, the highest position a woman had ever held in the federal government up to that time.

[143] In Wilson's first month in office, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson brought up the issue of segregating workplaces in a cabinet meeting and urged the president to establish it across the government, in restrooms, cafeterias and work spaces.

Following Wilson's appointment of Josephus Daniels as Secretary of the Navy, a system of Jim Crow was swiftly implemented with ships, training facilities, restrooms, and cafeterias all becoming segregated.

He further stated, "I say plainly that every American who takes part in the action of mob or gives it any sort of continence is no true son of this great democracy but its betrayer, and ...[discredits] her by that single disloyalty to her standards of law and of rights.

[159] Wilson's foreign policy was based on an idealistic approach to liberal internationalism that sharply contrasted with realist conservative nationalism of Taft, Roosevelt, and William McKinley.

After the war began, Wilson told the Senate that the United States, "must be impartial in thought as well as in action, must put a curb upon our sentiments as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference of one party to the struggle before another."

[198][199] New, well-funded organizations sprang up to appeal to the grassroots, including the American Defense Society (ADS) and the National Security League, both of which favored entering the war on the side of the Allies.

Anti-war sentiment was strong among many groups inside and outside of the party, including women,[203] Protestant churches,[204] labor unions,[205] and Southern Democrats like Claude Kitchin, chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee.

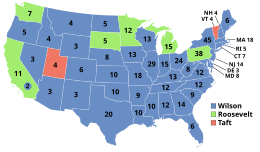

[213] The declaration of war by the United States against Germany passed Congress by strong bipartisan majorities on April 6, 1917, with opposition from ethnic German strongholds and remote rural areas in the South.

Clemenceau especially sought onerous terms for Germany, while Lloyd George supported some of Wilson's ideas but feared public backlash if the treaty proved too favorable to the Central Powers.

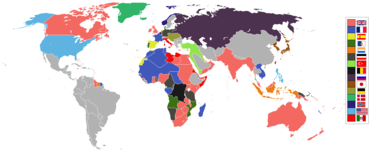

Wilson agreed to the creation of mandates in former German and Ottoman territories, allowing the European powers and Japan to establish de facto colonies in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

[235] Wilson himself presided over the committee that drafted the covenant, which bound members to oppose "external aggression" and to agree to peacefully settle disputes through organizations like the Permanent Court of International Justice.

Despite his weakened physical condition following the Paris Peace Conference, Wilson decided to barnstorm the Western states, scheduling 29 major speeches and many short ones to rally support.

Robert Maddox wrote, "The immediate effect of the intervention was to prolong a bloody civil war, thereby costing thousands of additional lives and wreaking enormous destruction on an already battered society.

[252] Richard G. Hovannisian states that Wilson "made all the wrong arguments" for the mandate and focused less on the immediate policy than on how history would judge his actions: "[he] wished to place it clearly on the record that the abandonment of Armenia was not his doing.

Many expressed qualms about Wilson's fitness for the presidency at a time when the League fight was reaching a climax, and domestic issues such as strikes, unemployment, inflation and the threat of Communism were ablaze.

In his acceptance speech on September 2, 1916, Wilson pointedly warned Germany that submarine warfare resulting in American deaths would not be tolerated, saying "The nation that violates these essential rights must expect to be checked and called to account by direct challenge and resistance.

At Wilson's request, Owen highlighted federal legislation to promote workers' health and safety, prohibit child labor, provide unemployment compensation and establish minimum wages and maximum hours.

Wilson, in turn, included in his draft platform a plank that called for all work performed by and for the federal government to provide a minimum wage, an eight-hour day and six-day workweek, health and safety measures, the prohibition of child labour, and (his own additions) safeguards for female workers and a retirement program.

When the 1920 Republican National Convention met in June 1920, none of the three major contenders were able to accrue enough support to win the nomination, and party leaders put forward various favorite son candidates.