Winter Palace

Following the February Revolution of 1917, the palace operated for a short time as the seat of the Russian Provisional Government, ultimately led by Alexander Kerensky.

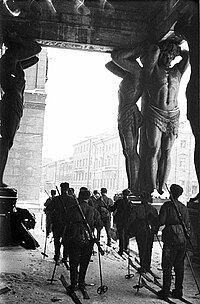

Later that same year a detachment of Red Guard soldiers and sailors stormed the palace—a defining moment in the birth of the Soviet state, overthrowing the Provisional Government.

[18] A diplomat of the time, who described the city as "a heap of villages linked together, like some plantation in the West Indies", just a few years later called it "a wonder of the world, considering its magnificent palaces".

Wolves roamed the squares at night while bands of discontented pressed serfs, imported to build the Tsar's new city and Baltic fleet, frequently rebelled.

She instructed the Russian nobility to replace their plain furniture with that of mahogany and ebony,[24] while her own tastes in interior decoration ran to a dressing table of solid gold and an "easing stool" of silver, studded with rubies.

The infant Tsar Ivan VI, succeeding Anna in 1740, was soon deposed in a bloodless coup d'état by Grand Duchess Elizabeth, a daughter of Peter the Great.

[27] Though the labourers earned a monthly wage of just one ruble, the cost of the project exceeded the budget, so much so that work ceased due to lack of resources despite the Empress' obsessive desire for rapid completion.

Catherine had been impressed by the French architect Jean-Baptiste Vallin de la Mothe, who designed the Imperial Academy of Arts (also in Saint Petersburg) and commissioned him to add a new wing to the Winter Palace.

Just twenty years earlier, so scarce were the furnishings of the Imperial palaces that bedsteads, mirrors, tables and chairs had to be conveyed between Moscow and Saint Petersburg each time the court moved.

In the first days of his reign, the new Tsar (reported by the British Ambassador to be "not in his senses"[39]) augmented the number of troops stationed at the Winter Palace, positioning sentry boxes every few metres around the building.

Following the restoration work after World War II, it was painted green with the ornament depicted in white, the standard Soviet color scheme for Baroque buildings.

Immediately adjacent to these galleries celebrating the French defeat, were rooms (18) where Maximilian, Duke of Leuchtenberg, Napoleon's step-grandson and the Tsar's son-in-law, lived during the early days of his marriage.

"During the great frosts 6000 workmen were continually employed; of these a considerable number died daily, but the victims were instantly replaced by other champions brought forward to perish.

[52] Following the fire, the exterior, most of the principal state suites, the Jordan staircase and the Grand Church were restored to their original design and decoration by the architect Vasily Stasov.

[52] The smaller and more private rooms of the palace were altered and decorated in various 19th-century contemporary styles by Alexander Briullov according to whims and fashion of their intended occupants, ranging from Gothic to rococo.

[52] The Tsarevna's crimson boudoir (23), in the private Imperial apartments, was a faithful reproduction of the rococo style, which Catherine II and her architects started to eliminate from the palace less than 50 years earlier.

In 1839, German architect Leo von Klenze drew up the plans and their execution was overseen by Vasily Stasov, assisted by Alexander Briullov and Nikolai Yefimov.

This attempt on the Tsar's life was organized by a group known as Narodnaya Volya (Will of the People) and led by an "unsmiling fanatic", Andrei Zhelyabov, and his mistress Sophia Perovskaya, who later became his wife.

On 4 March 1880, The New York Times reported "the dynamite used was enclosed in an iron box, and exploded by a system of clockwork used by the man Thomas in Bremen some years ago.

The Tsar was highly interested in the running costs of the palace, insisting that table linen was not to be changed daily, and that candles and soap were not replaced until completely spent.

[34] Empress Maria Feodorovna (Dagmar of Denmark), the wife of Alexander III, saw that a garden was laid out in the centre of the main courtyard in 1885, an area previously cobbled and lacking vegetation.

Court architect Nikolai Gornostayev designed a garden surrounded by a granite plinth and a fountain, and planted trees in the courtyard, laying limestone pavements along the walls of the palace.

This was surrounded originally (until 1920, when they were demolished and partially moved to the January 9th Gardens, where today they still stand) by a high wall topped with railings, with majestic gates where a guard was always posted.

Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich recalled the occasion as "the last spectacular ball in the history of the empire...[but] a new and hostile Russia glared through the large windows of the palace...while we danced, the workers were striking and the clouds in the Far East were hanging dangerously low.

"[81] The entire Imperial family, the Tsar as Alexei I, the Empress as Maria Miloslavskaya, all dressed in rich 17th century attire, posed in the Hermitage Theatre, many wearing priceless original items brought specially from the Kremlin,[82] for what was to be their final photograph together.

The massacre was sparked when a Russian Orthodox priest and popular working class leader, Father Gapon, announced his intention to lead a peaceful protest of 100,000 unarmed striking workers to present a petition to the Tsar, to call for fundamental reforms and the founding of a constituent parliament.

Following Rasputin's murder by the Tsar's nephew-in-law in December 1916, the Empress' decisions and appointments became more erratic and the situation worsened and Saint Petersburg fell into the full grip of revolution.

In February 1917, the Russian Provisional Government, led by Alexander Kerensky, based itself in the north west corner of the palace with the Malachite Room (4) being the chief council chamber.

[91] All military personnel in the city pledged support to the Bolsheviks, who accused Kerensky's Government of wishing to "surrender Petrograd to the Germans so as to enable them to exterminate the revolutionary garrison.

Arguably the largest and best stocked wine cellar in history,[92] it contained the world's finest vintages, including the Tsar's favourite, and priceless, Château d'Yquem 1847.