Witch hunt

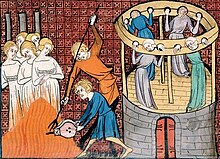

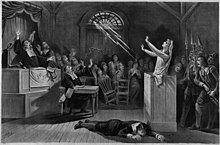

An intensive period of witch-hunts occurring in Early Modern Europe and to a smaller extent Colonial America, took place from about 1450 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Counter Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 35,000 to 60,000 executions.

In current language, "witch-hunt" metaphorically means an investigation that is usually conducted with much publicity, supposedly to uncover subversive activity, disloyalty, and so on, but with the real purpose of harming opponents.

[4] The wide distribution of the practice of witch hunts in geographically and culturally separated societies (Europe, Africa, New Guinea) since the 1960s has triggered interest in the anthropological background of this behaviour.

[5] Reports on indigenous practices in the Americas, Asia and Africa collected during the early modern Age of Exploration have been taken to suggest that not just the belief in witchcraft but also the periodic outbreak of witch-hunts are a human cultural universal.

Deuteronomy 18:10–12 states: "No one shall be found among you who makes a son or daughter pass through fire, who practices divination, or is a soothsayer, or an augur, or a sorcerer, or one that casts spells, or who consults ghosts or spirits, or who seeks oracles from the dead.

In the Judaean Second Temple period, Rabbi Simeon ben Shetach in the 1st century BC is reported to have sentenced to death eighty women who had been charged with witchcraft on a single day in Ascalon.

[14]: 135 The most detailed account of a trial for witchcraft in Classical Greece is the story of Theoris of Lemnos, who was executed along with her children some time before 338 BC, supposedly for casting incantations and using harmful drugs.

The Lombard code of 643 AD states: Let nobody presume to kill a foreign serving maid or female servant as a witch, for it is not possible, nor ought to be believed by Christian minds.

Such, for example, were nocturnal riding through the air, the changing of a person's disposition from love to hate, the control of thunder, rain, and sunshine, the transformation of a man into an animal, the intercourse of incubi and succubi with human beings, and other such superstitions.

[37] Augustine and his adherents like Saint Thomas Aquinas nevertheless promulgated elaborate demonologies, including the belief that humans could enter pacts with demons, which became the basis of future witch hunts.

According to Snorri Sturluson, King Olaf Trygvasson furthered the Christian conversion of Norway by luring pagan magicians to his hall under false pretenses, barring the doors and burning them alive.

Although it has been proposed that the witch-hunt developed in Europe from the early 14th century, after the Cathars and the Knights Templar were suppressed, this hypothesis has been rejected independently by virtually all academic historians (Cohn 1975; Kieckhefer 1976).

[e][42] Although Pope John XXII had later authorized the Inquisition to prosecute sorcerers in 1320,[43] inquisitorial courts rarely dealt with witchcraft save incidentally when investigating heterodoxy.

The accusations of witchcraft are, in this case, considered to have been a pretext for Hermann to get rid of an "unsuitable match," Veronika being born into the lower nobility and thus "unworthy" of his son.

[46] The resurgence of witch-hunts at the end of the medieval period, taking place with at least partial support or at least tolerance on the part of the Church, was accompanied with a number of developments in Christian doctrine, for example, the recognition of the existence of witchcraft as a form of Satanic influence and its classification as a heresy.

As Renaissance occultism gained traction among the educated classes, the belief in witchcraft, which in the medieval period had been part of the folk religion of the uneducated rural population at best, was incorporated into an increasingly comprehensive theology of Satan as the ultimate source of all maleficium.

[i] In 1484, Pope Innocent VIII issued Summis desiderantes affectibus, a Papal bull authorizing the "correcting, imprisoning, punishing and chastising" of devil-worshippers who have "slain infants", among other crimes.

To justify the killings, some Christians of the time and their proxy secular institutions deemed witchcraft as being associated to wild Satanic ritual parties in which there was naked dancing and cannibalistic infanticide.

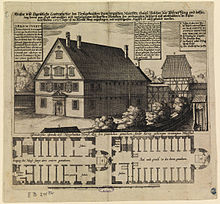

In 1615, she was called a witch by a female neighbor in the duchy of Württemberg following a dispute with her of having given her a bitter drink that had made her ill. She was held captive for over a year and threatened with torture, but was finally acquitted thanks to her son's efforts.

On the basis of this evidence, Scarre and Callow asserted that the "typical witch was the wife or widow of an agricultural labourer or small tenant farmer, and she was well known for a quarrelsome and aggressive nature."

The leader of the witch-hunt, often a prominent figure in the community or a "witch doctor", may also gain economic benefit by charging for an exorcism or by selling body parts of the murdered.

"[116] In 2006, an illiterate Saudi woman, Fawza Falih, was convicted of practising witchcraft, including casting an impotence spell, and sentenced to death by beheading, after allegedly being beaten and forced to fingerprint a false confession that had not been read to her.

[120] In 2009, Ali Sibat, a Lebanese television presenter who had been arrested whilst on a pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia, was sentenced to death for witchcraft arising out of his fortune-telling on an Arab satellite channel.

[121] His appeal was accepted by one court, but a second in Medina upheld his death sentence again in March 2010, stating that he deserved it as he had publicly practised sorcery in front of millions of viewers for several years.

[127] Reports by U.N. agencies, Amnesty International, Oxfam and anthropologists show that "attacks on accused sorcerers and witches – sometimes men, but most commonly women – are frequent, ferocious and often fatal.

[148] In 2010, Sarwa Dev Prasad Ojha, Minister for Women and Social Welfare, said, "Superstitions are deeply rooted in our society, and the belief in witchcraft is one of the worst forms of this.

[150] Countries particularly affected by this phenomenon include South Africa,[151] Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Zambia.

After white rule of Africa, beliefs in sorcery and witchcraft grew, possibly because of the social strain caused by new ideas, customs and laws, and also because the courts no longer allowed witches to be tried.

[160] In March 2009, Amnesty International reported that up to 1,000 people in the Gambia had been abducted by government-sponsored "witch doctors" on charges of witchcraft, and taken to detention centers where they were forced to drink poisonous concoctions.

[174] The National Rifle Association of America used the term in an unsuccessful bid to dismiss the New York attorney general's lawsuit against the organization for alleged fraud.