Wolf interval

Strictly, the term refers to an interval produced by a specific tuning system, widely used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: the quarter-comma meantone temperament.

[3] More broadly, it is also used to refer to similar intervals (of close, but variable magnitudes) produced by other tuning systems, including Pythagorean and most meantone temperaments.

When the twelve notes within the octave of a chromatic scale are tuned using the quarter-comma meantone systems of temperament, one of the twelve intervals apparently spanning seven semitones is actually a diminished sixth, which turns out to be much wider than the in-tune genuine fifths,[a] In mean-tone systems, this interval is usually from C♯ to A♭ or from G♯ to E♭ but can be moved in either direction to favor certain groups of keys.

Conversely, the diminished sixth used as a substitute is severely dissonant: It sounds like the howl of a wolf, because of a phenomenon called beating.

Besides the above-mentioned quarter comma meantone, other tuning systems may produce severely dissonant diminished sixths.

In all meantone tuning systems, sharps and flats are not equivalent; a relic of which, that persists in modern musical practice, is to fastidiously distinguish the musical notation for two notes which are the same pitch in equal temperament ("enharmonic") and played with the same key on an equal tempered keyboard (such as C♯ and D♭, or E♯ and F♮), despite the fact that they are the same in all but theory.

[c] In meantone temperament tuning systems, the twelfth and last fifth does not exist in the 12 note octave on the keyboard.

[e] This limitation on the set meantone notes and their sharps and flats that can be tuned on a keyboard at any one time, was the main reason that Baroque period keyboard and orchestral harp performers were obliged to retune their instruments in mid-performance breaks, in order to make available all the accidentals called for by the next piece of music.

For expediency, keyboard players substitute the wrong diminished sixth interval for a genuine meantone fifth (or neglect retuning their instrument).

A meantone keyboard that allowed unlimited modulation theoretically would require an infinite number of separate sharp and flat keys, and then double sharps and double flats, and so on: There must inevitably be missing pitches on a standard keyboard with only 12 notes in an octave.

Meantone tunings with slightly flatter fifths produce even closer approximations to the subminor and supermajor thirds and corresponding triads.

The wolf fifth of quarter-comma meantone can be approximated by the 7-limit just interval 49:32, which has a size of 737.652 cents.

It is also important to note that the two fifths, three minor thirds, and three major sixths marked in orange in the tables (ratio 40:27, 32:27, and 27:16; or G↓, E♭↓, and A↑), even though they do not completely meet the conditions to be wolf intervals, deviate from the corresponding pure ratio by an amount (1 syntonic comma, i.e., 81:80, or about 21.5 cents) large enough to be clearly perceived as dissonant.

For example, the Wicki keyboard shown in Figure 1 is generated by the same musical intervals as the syntonic temperament—that is, by the octave and tempered perfect fifth—so they are isomorphic.

However, such edge conditions produce wolf intervals only if the isomorphic keyboard has fewer buttons per octave than the tuning has enharmonically distinct notes.

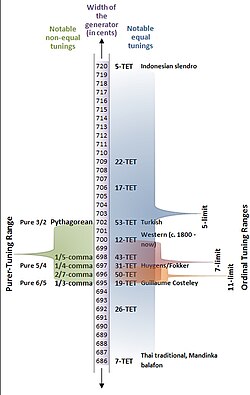

[9] Plamondon, Milne & Sethares (2009),[9] Figure 2, shows the valid tuning range of the syntonic temperament.