Women's suffrage in New Jersey

One of the early suffrage protests took place when Lucy Stone refused to pay her property taxes in 1857 under the Revolutionary slogan of "taxation without representation".

In the late 1880s, a rural school suffrage bill that affected communities with open meetings, was passed, allowing some women limited access to vote.

Suffragists continued the fight in the state, with the notable addition of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU), started by New Jersey's Alice Paul.

[13] Women of the time expressed their political ideas in newspapers, some writing under the names "Mary Meanwell," "Miss Bannerman," and a "Quaker Woman.

[19] In 1807, there was a tight election that was "hotly contested" because of fraudulent activity where some voters may have voted more than once, with some men even going so far as to dress as women to perpetrate the fraud.

[23] In 1807, John Condit, who had only won his position by a narrow margin, introduced another act to overturn the right of women and black people to vote in New Jersey.

[41] In early 1867, Stone and Antoinette Brown Blackwell created a petition to send to the New Jersey legislature to remove the words "white male" from the voting qualifications in the state constitution.

[45] The Vineland ballot box for women was created by teacher and farmer, Susan Pecker Fowler, who made it from blueberry cartons and green fabric.

"[49] In the early 1880s, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) grew in New Jersey, especially among African-American women who formed separate groups and committees.

[53] Seabrook worked on the New Jersey WCTU's legislative committee and learned effective strategies for conducting petition drives and lobbying the legislature.

[54] In 1884, Seabrook and suffragists Henry Blackwell and Phebe Hanaford began to work together and were able to get some support for women's suffrage from state legislators.

[58] In 1890, the New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association (NJWSA) reorganized with the help of Mary Dudley Hussey and elected Judge John Whitehead as the president.

[64] William Outis Allison who ran for road commissioner and lost, claimed that his opponent, Clinton Hamlin Blake, had won due to illegal voting.

[68] NJWSA president, Florence Howe Hall hoped that this ruling might inspire more people to advocate for full women's suffrage in the state.

[69] In 1909, Emma O. Gantz and Martha Klatschken formed the Progressive Woman Suffrage Society which held the state's first open air meetings.

[75] Sophia Loebinger gave a speech in Palisades Amusement Park in 1909 where she discussed the influence that Native Americans had in suffrage issues and brought three Iroquois people with her.

[83] Working woman, Melilnda Scott, participated in the hearing, marking the first time a prominent labor activist joined the suffragists in New Jersey.

[90] Several people, including Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Laddys, Linton Satterthwaite, Rhea Vickers, and Fanny Garrison Villard all testified on behalf of women's suffrage.

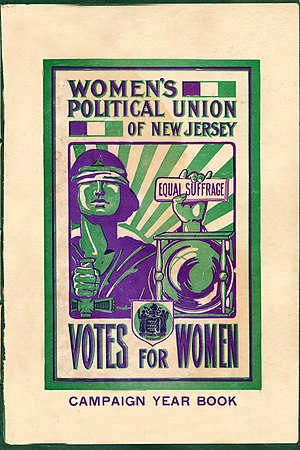

[92] The Equality League, run by Van Winkle, changed their name to the Women's Political Union of New Jersey (WPUNJ) and affiliated with NJWSA in 1912.

[102] In February 1913, a "Votes for Women Special" train left Newark to carry suffrage supporters to Trenton to attend the hearing of the bill.

Du Bois, Thomas Edison, John Franklin Fort, Theodore Roosevelt, and eventually, President Wilson, came out in support of women's suffrage in New Jersey during this campaign.

"[131] On December 1, 1915, a chapter of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU) was formed in New Jersey with Alison Turnbull Hopkins serving as the president.

[135] The Eastern Campaign of the CU held a mass meeting in Atlantic City to discuss their opposition towards Democratic members of the government who were blocking the federal suffrage amendment.

[142] Feickert started chairing a new group, the New Jersey Suffrage Ratification Committee (NJSRC), to fight for the state legislature to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

[143] Suffragists filled the chamber to listen to the debate and early into the night the Assembly passed the resolution on February 10, leading to women celebrating in the halls of the building after the passage.

Du Bois publicly supported the 1915 New Jersey campaign, writing in The Crisis, "To say the woman is weaker than man is sheer rot: It is the same sort of thing we hear about the 'darker races' and 'lower classes.

'"[118] Mary Church Terrell campaigned in New Jersey in October, urging black men to vote for the women's suffrage amendment.

[127] In a New York Times article, the black poll watchers were blamed for losing the women's suffrage amendment in Atlantic County.

"[148] Florence Spearing Randolph was involved with getting the New Jersey State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs (NJFCWC) to affiliate with the NJWSA which took place in November 1917.

[91] The anti-suffragists decided to organize after the hearing, creating the New Jersey Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NJAOWS) in Trenton on April 14, 1912.