Women in Church history

[2] Later, as religious sisters and nuns, women came to play an important role in Christianity through convents and abbeys and have continued through history to be active—particularly in the establishment of schools, hospitals, nursing homes and monastic settlements.

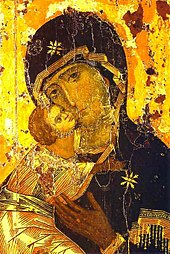

Within Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, particular place of veneration has been reserved for Mary, the Mother of Jesus, which has kept a model of maternal virtue central to their vision of Christianity.

The New Testament of the Bible refers to a number of women in Jesus' inner circle (notably his mother Mary, for whom the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodoxy hold a special place of honour, and St. Mary Magdalene, who discovered the empty tomb of Christ), although the Catholic Church teaches that Christ appointed only male Apostles (from the Greek apostello "to send forth").

Blainey points to several Gospel accounts of Jesus imparting important teachings to women: his meeting with the Samaritan woman at the well, his anointing by Mary of Bethany, his public admiration for a poor widow who donated some copper coins to the Temple in Jerusalem, his stepping to the aid of the woman accused of adultery, and the presence of Mary Magdalene at his side as he was crucified.

Jewish women disciples, including Mary Magdalene, Saint Joanna, and Susanna, had accompanied Jesus during his ministry and supported him out of their private means.

[9] Although the details of these gospel stories may be questioned, in general they reflect the prominent historical roles women played in Jesus' ministry as disciples.

[10] This large female membership likely stemmed in part from the early church's informal and flexible organization offering significant roles to women.

"[11] Women may also have been driven from Judaism to Christianity through the taboos and rituals related to the menstrual cycle, and a society preference for male over female children.

His letter to the Galatians was emphatic in defying the prevailing culture, and his words must have been astonishing to women encountering Christian ideas for the first time: 'there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Jesus Christ'.

[21] As Western Europe transitioned from the Classical to Medieval Age, the male hierarchy with the Pope as its summit became a central player in European politics, however many women leaders also emerged at various levels within the Church.

In the West, the Roman Catholic Church was the major unifying cultural influence in Europe during the Middle Ages with its selection from Latin learning, preservation of the art of writing, and a centralized administration through its network of bishops.

From the 5th century onward, Christian convents provided an alternative for some women to the path of marriage and child-rearing and allowed them to acquire literacy and learning, and play a more active religious role.

The Celtic Church played an important role in restoring Christianity to Western Europe following the Fall of Rome, due in part to the work of nuns like Brigid.

Mary Magdalene's Feast Day was celebrated in earnest from the 8th century on and composite portraits of her developed from Gospel references to other women Jesus met.

[28] Monastic orders came to include key Catholic figures such as Doctor of the Church Teresa of Ávila, whose influence on practices such as Christian meditation continues to date.

Of Isabella and Ferdinand, it says: "The good government of the Catholic sovereigns brought the prosperity of Spain to its apogee, and inaugurated that country's Golden Age".

The throne was reserved for males, though women such as Theophanu and Maria Theresa of Austria, controlled the power and served as de facto Empresses regnant.

Following victories, her husband, Francis Stephen, was chosen as Holy Roman Emperor in 1745, confirming Maria Theresa's status as a European leader.

On religion she pursued a policy of cujus regio, ejus religio, keeping Catholic observance at court and frowning on Judaism and Protestantism—but the ascent of her son as co-regnant Emperor saw restrictions placed on the power of the Church in the Empire.

One notable damenstift member was Catharina von Schlegel (1697–1768) who wrote the hymn that was translated into English as Be still, my soul, the Lord is on thy side.

(Clarke)[43] Puritan theologian Matthew Poole (1624–1679) concurred with Wesley, adding, "But setting aside that extraordinary case of a special afflatus, [strong Divine influence] it was, doubtless, unlawful for a woman to speak in the church.

However, the Protestant belief that all people should be able to read the Bible, wrote Blainey, led to an increase in female literacy, as a result of the opening of new schools, and the introduction of compulsory education for boys and girls in places like Lutheran Prussia beginning in 1717.

Thus, in the communities of Europe and North America that adopted Protestantism, the centuries-old rituals and theology associated with Mary and formal sainthood that had been built up by the Catholic tradition were largely expunged in the aftermath of the Reformation.

During the Baroque period, religious depictions of women in Catholic Europe became not only exuberant, but often highly sensual, as with the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

[48] The Little Sisters of the Poor was founded in the mid-19th century by Saint Jeanne Jugan near Rennes, France, to care for the many impoverished elderly who lined the streets of French towns and cities.

[53] For much of the early twentieth century, Catholic women continued to join religious institutes in large numbers, where their influence and control was particularly strong in the running of primary education for children, high schooling for girls, and in nursing, hospitals, orphanages and aged care facilities.

A number of beatifications and canonisations took place of Catholic women from all over the world: St. Josephine Bakhita was a Sudanese slave girl who became a Canossian nun; St. Katharine Drexel (1858–1955) worked for Native and African Americans; Polish mystic St. Maria Faustina Kowalska (1905–1938) wrote her influential spiritual diary;[54] and German nun Edith Stein who was murdered at Auschwitz.

Swedish born Elisabeth Hesselblad was listed among the "righteous among the nations" by Yad Vashem for her religious institute's work assisting Jews escape The Holocaust.

[56] She and two British women, Mother Riccarda Beauchamp Hambrough and Sister Katherine Flanagan have been beatified for reviving the Swedish Bridgettine Order of nuns and hiding scores of Jewish families in their convent during Rome's period of occupation under the Nazis.

Among the most famous women missionaries of the period was Mother Teresa of Calcutta, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979 for her work in "bringing help to suffering humanity".