Speech balloon

[2] Earlier, paintings, depicting stories in subsequent frames, using descriptive text resembling bubbles-text, were used in murals, one such example written in Greek, dating to the 2nd century, found in Capitolias, today in Jordan.

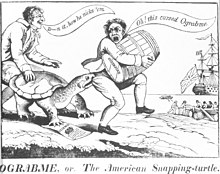

Word balloons (also known as "banderoles") began appearing in 18th-century printed broadsides, and political cartoons from the American Revolution (including some published by Benjamin Franklin) often used them—as did cartoonist James Gillray in Britain.

[6] With the development of the comics industry during the 20th century, the appearance of speech balloons has become increasingly standardized, though the formal conventions that have evolved in different cultures (USA as opposed to Japan, for example) can be quite distinct.

In the UK in 1825 The Glasgow Looking Glass, regarded as the world's first comics magazine, was created by English satirical cartoonist William Heath.

In Europe, where text comics were more common, the adoption of speech balloons was slower, with well-known examples being Alain Saint-Ogan's Zig et Puce (1925), Hergé's The Adventures of Tintin (1929), and Rob-Vel's Spirou (1938).

During the Gulf War, an American propaganda leaflet that used a thought bubble proved puzzling to Iraqi soldiers: according to one PSYOP specialist this was because the technique was not known in Iraq, and readers "had no idea why Saddam's head was floating in the air.

An in-panel character (one who is fully or mostly visible in the panel of the strip of comic that the reader is viewing) uses a bubble with a pointer, termed a tail, directed towards the speaker.

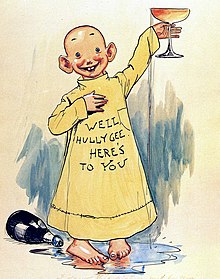

The first is a standard speech bubble with a tail pointing toward the speaker's position (sometimes seen with a symbol at the end to represent specific characters).

In comics, a bubble without a tail means that the speaker is not merely outside the reader's field of view, but also invisible to the viewpoint character, often as an unspecified member of a crowd.

Characters distant (in space or time) from the scene of the panel can still speak, in squared bubbles without a tail; this usage, equivalent to voice-over for movies, is not uncommon in American comics for dramatic contrast.

In contrast to captions, the corners of such balloons never coincide with those of the panel; for further distinction, they often have a double outline, a different background color, or quotation marks.

Common ones include the following: Captions are generally used for narration purposes, such as showing location and time, or conveying editorial commentary.

In the famous French comic series Asterix, Goscinny and Uderzo use bubbles without tails to indicate a distant or unseen speaker.

For examples, the main character, the gloomy Dream, speaks in wavy-edged bubbles, completely black, with similarly wavy white lettering.

[10] For Mad magazine's recurring comic strip Monroe, certain words are written larger or in unusual fonts for emphasis.

One of the universal emblems of the art of comics is the use of a single punctuation mark to depict a character's emotions, much more efficiently than any possible sentence.

This device is used much in the European comic tradition, the Belgian artist Hergé's The Adventures of Tintin series being a good example.

The ellipsis, along with the big drop of sweat on the character's temple – usually depicting shame, confusion, or embarrassment caused by other people's actions – is one of the Japanese graphic symbols that have become used by other comics around the world, although they are still rare in Western tradition.

Some comics will have the actual foreign language in the speech balloon, with the translation as a footnote; this is done with Latin aphorisms in Asterix.

Another convention is to put the foreign speech in a distinctive lettering style; for example, Asterix's Goths speak in blackletter.

It is a convention for American comics that the sound of a snore is represented as a series of Z's, dating back at least to Rudolph Dirks' early 20th-century strip The Katzenjammer Kids.

The above-mentioned Albert Uderzo in the Asterix series decorates speech bubbles with beautiful flowers depicting an extremely soft, sweet voice (usually preceding a violent outburst by the same character).

In comics that are usually addressed to children or teenagers, bad language is censored by replacing it with more or less elaborate drawings and expressionistic symbols.

Although not specifically addressed to children, Mortadelo was initiated during Francisco Franco's dictatorship, when censorship was common and rough language was prohibited.

When Mortadelo was portrayed in a movie by Spanish director Javier Fesser in 2003, one of the critiques made to his otherwise successful adaptation was the character's use of words that never appeared in the comics.

In several occasions, comics artists have used balloons (or similar narrative devices) as if they have true substance, usually for humorous meta-like purposes.

In Peanuts, for example, the notes played by Schroeder occasionally take substance and are used in various ways, including Christmas decorations or perches for birds.

In the novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit?, the last words of a murdered Toon (cartoon character) are found under his body in the form of a speech balloon.