Part of speech

Commonly listed English parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction, interjection, numeral, article, and determiner.

[5] For example: Because of such variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties, analysis of parts of speech must be done for each individual language.

[5] The classification of words into lexical categories is found from the earliest moments in the history of linguistics.

[6] In the Nirukta, written in the 6th or 5th century BCE, the Sanskrit grammarian Yāska defined four main categories of words:[7] These four were grouped into two larger classes: inflectable (nouns and verbs) and uninflectable (pre-verbs and particles).

[9] A century or two after the work of Yāska, the Greek scholar Plato wrote in his Cratylus dialogue, "sentences are, I conceive, a combination of verbs [rhêma] and nouns [ónoma]".

[11] By the end of the 2nd century BCE, grammarians had expanded this classification scheme into eight categories, seen in the Art of Grammar, attributed to Dionysius Thrax:[12] It can be seen that these parts of speech are defined by morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria.

[14][15] The Latin names for the parts of speech, from which the corresponding modern English terms derive, were nomen, verbum, participium, pronomen, praepositio, adverbium, conjunctio and interjectio.

Additionally, there are other parts of speech including particles (yes, no)[a] and postpositions (ago, notwithstanding) although many fewer words are in these categories.

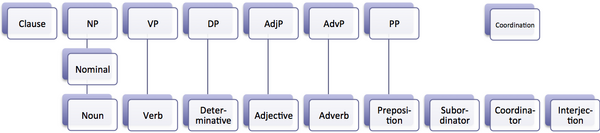

The classification below, or slight expansions of it, is still followed in most dictionaries: English words are not generally marked as belonging to one part of speech or another; this contrasts with many other European languages, which use inflection more extensively, meaning that a given word form can often be identified as belonging to a particular part of speech and having certain additional grammatical properties.

[20][21] Modern linguists have proposed many different schemes whereby the words of English or other languages are placed into more specific categories and subcategories based on a more precise understanding of their grammatical functions.

Open classes are generally lexical categories in the stricter sense, containing words with greater semantic content,[26] while closed classes are normally functional categories, consisting of words that perform essentially grammatical functions.

are being added to the language constantly (including by the common process of verbing and other types of conversion, where an existing word comes to be used in a different part of speech).

[31] Basque verbs are also a closed class, with the vast majority of verbal senses instead expressed periphrastically.

This is mostly in casual speech for borrowed words, with the most well-established example being sabo-ru (サボる, cut class; play hooky), from sabotāju (サボタージュ, sabotage).

The case is similar in languages of Southeast Asia, including Thai and Lao, in which, like Japanese, pronouns and terms of address vary significantly based on relative social standing and respect.