Word

[1] Despite the fact that language speakers often have an intuitive grasp of what a word is, there is no consensus among linguists on its definition and numerous attempts to find specific criteria of the concept remain controversial.

[2] Different standards have been proposed, depending on the theoretical background and descriptive context; these do not converge on a single definition.

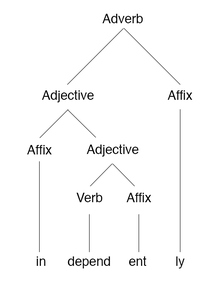

[2]: 768 In English and many other languages, the morphemes that make up a word generally include at least one root (such as "rock", "god", "type", "writ", "can", "not") and possibly some affixes ("-s", "un-", "-ly", "-ness").

Since the beginning of the study of linguistics, numerous attempts at defining what a word is have been made, with many different criteria.

[4]: 6 These include definitions on the phonetic and phonological level, that it is the smallest segment of sound that can be theoretically isolated by word accent and boundary markers; on the orthographic level as a segment indicated by blank spaces in writing or print; on the basis of morphology as the basic element of grammatical paradigms like inflection, different from word-forms; within semantics as the smallest and relatively independent carrier of meaning in a lexicon; and syntactically, as the smallest permutable and substitutable unit of a sentence.

[4]: 1 Much of the difficulty stems from the eurocentric bias, as languages from outside of Europe may not follow the intuitions of European scholars.

It is a unit larger or equal to a syllable, which can be distinguished based on segmental or prosodic features, or through its interactions with phonological rules.

In Hungarian, dental consonants /d/, /t/, /l/ or /n/ assimilate to a following semi-vowel /j/, yielding the corresponding palatal sound, but only within one word.

The prototypical example of this rule comes from Sanskrit; however, initial consonant mutation in contemporary Celtic languages or the linking r phenomenon in some non-rhotic English dialects can also be used to illustrate word boundaries.

For example, there is little doubt that in Turkish the lexeme for house should include nominative singular ev and plural evler.

There are also lexemes such as "black and white" or "do-it-yourself", which, although consisting of multiple words, still form a single collocation with a set meaning.

According to this theory, semantic primes serve as the basis for describing the meaning, without circularity, of other words and their associated conceptual denotations.

[11][12] In the Minimalist school of theoretical syntax, words (also called lexical items in the literature) are construed as "bundles" of linguistic features that are united into a structure with form and meaning.

For example, reflexive verbs in the French infinitive are separate from their respective particle, e.g. se laver ("to wash oneself"), whereas in Portuguese they are hyphenated, e.g. lavar-se, and in Spanish they are joined, e.g.

Mandarin Chinese is a highly analytic language with few inflectional affixes, making it unnecessary to delimit words orthographically.

However, there are many multiple-morpheme compounds in Mandarin, as well as a variety of bound morphemes that make it difficult to clearly determine what constitutes a word.

[14]: 56 Japanese uses orthographic cues to delimit words, such as switching between kanji (characters borrowed from Chinese writing) and the two kana syllabaries.

This is a fairly soft rule, because content words can also be written in hiragana for effect, though if done extensively spaces are typically added to maintain legibility.

Words may undergo different morphological processes which are traditionally classified into two broad groups: derivation and inflection.

[19][3]: 13:631 On the other hand, in Eskimo–Aleut languages all content words can be analyzed as nominal, with agentive nouns serving the role closest to verbs.

Finally, in some Austronesian languages it is not clear whether the distinction is applicable and all words can be best described as interjections which can perform the roles of other categories.

Adjectives ('happy'), quantifiers ('few'), and numerals ('eleven') were not made separate in those classifications due to their morphological similarity to nouns in Latin and Ancient Greek.

[3]: 13:629 In Indian grammatical tradition, Pāṇini introduced a similar fundamental classification into a nominal (nāma, suP) and a verbal (ākhyāta, tiN) class, based on the set of suffixes taken by the word.

[4]: 269 The word (dictiō) was defined as the minimal unit of an utterance (ōrātiō), the expression of a complete thought.