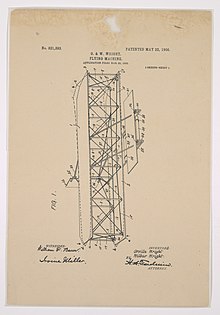

Wright brothers patent war

They were two Americans who are widely credited with inventing and building the world's first flyable airplane and making the first controlled, powered, and sustained heavier-than-air human flight on December 17, 1903.

In 1910, they won their initial lawsuit against Curtiss, when Federal Judge John Hazel ruled: It further appears that the defendants now threaten to continue such use for gain and profit, and to engage in the manufacture and sale of such infringing machine, thereby becoming an active rival of complainant in the business of constructing flying-machines embodying the claims in suit, but such use of the infringing machine it is the duty of this Court on the papers presented to enjoin.

[13] Perhaps as a consequence, airplane development in the United States fell so far behind Europe[8] that in World War I, American pilots were forced to fly European combat aircraft instead.

[8][22] Soon after the Wright brothers demonstrated their airplane, numerous others involved in similar efforts at the time sought to gain credit for their achievements, whether justified or not.

As noted in the New York Times in 1910, "a highly significant fact that, until the Wright brothers succeeded, all attempts with heavier-than-air machines were dismal failures, but since they showed that the thing could be done everybody seems to be able to do it.

"[27] This competition quickly devolved into a patent war including 12 major lawsuits, extensive media coverage and a secret effort by Glenn Curtiss and the Smithsonian Institution to discredit the Wright brothers.

A German court ruled the patent not valid due to prior disclosure in speeches by Wilbur Wright in 1901 and Octave Chanute in 1903.

[34] Aviation development in the U.S. was suppressed to such an extent that, when the country entered World War I, no acceptable American-designed aircraft were available,[14][16] and U.S. forces were compelled to use French airplanes.

[17] This claim has been disputed by researchers Katznelson and Howells, who assert that before World War I "aircraft manufacturers faced no patent barriers.

Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the verdict in favor of the Wrights against the Curtiss company, which continued to avoid penalties through legal tactics.

[36][37] It took until 1928 for the Smithsonian Board of Regents to pass a resolution acknowledging that the Wright brothers deserved the credit for "the first successful flight with a power-propelled heavier-than-air machine carrying a man.

[8] At the same time (and in response, some suggest) Glenn Curtiss and his company did the same with their numerous, and arguably important, aviation patents—driving up the cost of American aircraft.

The U.S. government, as a result of a recommendation from the newly established National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, pressured the industry to form a cross-licensing organization (in other terms a patent pool), the Manufacturer's Aircraft Association.

By this time, Wilbur had died (in May 1912) and Orville had sold his interest in the Wright Company to a group of New York financiers (in October 1915) and retired from the business.

It has been used as an example in recent cases, such as dealing with HIV antiretroviral drug patents to give access to otherwise expensive treatments in Africa.

In 1868, before the advent of powered, heavier-than-air aircraft — and within eleven years distant in time from the birth of all three of the involved parties in the American lawsuit — English inventor Matthew Piers Watt Boulton first patented ailerons.

[60] U.S. District Judge John R. Hazel, who heard the Wright lawsuit against Curtiss, found to the contrary, ruling in 1913 that Boulton's "assertions and suggestions were altogether too conjectural to teach others how to reduce them to practice, and therefore his patent is not anticipatory.

[62] New Zealander Richard Pearse may have made a powered flight in a monoplane that included small ailerons as early as 1902, but his claims are controversial (and sometimes inconsistent), and, even by his own reports, his aircraft were not well controlled.

[64] The Santos-Dumont 14-bis canard biplane was modified to add ailerons in late 1906, though it was never fully controllable in flight, likely due to its unconventional surfaces arrangement.