Wycliffe's Bible

The authorship, orthodoxy, usage, and ownership has been controversial in the past century, with historians now downplaying the certainty of past beliefs that the translations were made by controversial English theologian John Wycliffe of the University of Oxford directly or with a team including John Purvey and Nicholas Hereford to promote Wycliffite ideas, used by Lollards for clandestine public reading at their meetings, or contained heterodox translations antagonistic to Catholicism.

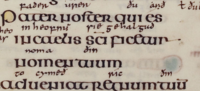

[6]: 236, 243 Many of these manuscripts have apparatus to link to the Sarum liturgical calendar and were apparently commissioned by clerical or religious patrons for professional use: about 40% have tables of lections (lists of Scripture readings) indicating the books were used in conjunction with the Mass or preparation of sermons.

Historian Elizabeth Solopova notes "in spite of many polemical claims that the translation would benefit the ‘poor’, ‘simple’ and ‘illiterates’, at the time when the production of WB had peaked in the first half of the 15th century the conditions for a wide use of the vernacular Bible by the laity were not yet fully established.

The LV, though somewhat improved, still retained a number of infelicities of style, some of which may reflect the contemporary transitions in Middle English grammar, as in its version of Genesis 1:3 below.

[8] Historian Mary Raschko attributes to Wycliffites three primary forms of gospel literature: Wycliffe's early Postilla super totam Bibliam were brief commentaries or notes on the whole Bible.

Wycliffe later wrote several long exegetical commentaries on Revelation and the four Gospels which included Middle English translations of the passages being discussed.

[28] The Oon of Foure was a gospel harmony in Middle English, a translation of Clement of Llanthony's 12th century Latin work Concordia quattuor evangelistarum, itself a collection of mainly patristic exegetical fragments whose extracted biblical passages often deviate from the Vulgate.

[29]: 86 Ten LV manuscripts begin with a so-called General Prologue (GP,[30] also known as Four and Twenty Books) written by "Simple Creature" that has also subsequently been attributed to Purvey from either 1395 or 1396.

[31] This prologue, analogous to the Prologus Galeatus, advocates reading the Old Testament, summarizes its books and relevant moral lessons, and explains the medieval four senses of Scripture and the interpretation rules of Augustine of Hippo and Isidore of Seville.

"[1] There are three alternative narratives about the so-called Wycliffite translations: The precise nature of Wyclif's connection with the production of the first English bible is shrouded in mystery [...].

[52] For example, the godparent system created a duty for laypeople to ensure that their godchildren had been taught and explained the Latin of the common prayers and meaning of the liturgy, independent of the clergy or schooling.

For Morey, "the Wycliffites are 'first' in their coordinated efforts to produce a complete scholarly English Bible" and their project was characterized by "care, prestige, and organization"[4]: 87 rather than operating in a vernacular vacuum.

[62]: 93 Wycliffe is said to have supported vernacular translations, purportedly saying "it helpeth Christian men to study the Gospel in that tongue in which they know best Christ's sentence".

[66]: 242, 395–97 The association between the Wycliffian Bibles (sometimes with a radical-in-parts prologue) and Lollardy, a sometimes-violent pre-Reformation movement that rejected many of the distinctive teachings of the Catholic Church, caused the Kingdom of England and the established Catholic Church in England to undertake a drastic campaign to suppress it, although the reality or legal basis of this suppression of the Middle English Bible translations has been disputed.

In 1377, Wycliffe published De Civili Dominio, which harshly criticized the church's wealth and argued that the king should confiscate ecclesiastical property.

He argued that Pope Innocent III's interpretation of the doctrine was not founded in scripture and contradicted the views of Jerome and Augustine, and therefore constituted apostasy.

[citation needed] In 1894, Irish Benedictine historian Dom Aidan Gasquet challenged the conventional attribution of the Middle English Bible to Wycliffe and his circle.

He had reviewed the EV and LV from a Catholic doctrinal perspective and found no translation errors that could have made the scriptural parts heretical.

[62] More recent scholars have provided several alternative creation sequences, that would also fit the evidence: for example that there was a previous existing Catholic EV that was glossed at Oxford University by e.g. scholars influenced by Wycliffe's biblicism, and re-translated as the LV (and the Paues Middle English New Testament) though not as a mammoth project; one of those involved later added the GP, as the project was hijacked by Wycliffite/Lollard radicals.

[49] This pestilent and wretched John Wyclif, of cursed memory, that son of the old serpent [...] endeavoured by every means to attack the very faith and sacred doctrine of Holy Church, devising—to fill up the measure of his malice—the expedient of a new translation of the Scriptures into the mother tongue.

Although Arundel had previously approved the Glossed Gospels in his role as Archbishop of York, he now began to oppose Middle English translations of the Bible.

[83] Deansley noted the early "episcopal policy to try to win over the scholarly Lollards by argument and benignancy" which won over Nicholas Hereford.

Even twenty years after Wycliffe's death, at the Oxford Convocation of 1407, it was solemnly voted that no new translation of the Bible should be made without prior approval.

[90] This translation, which became "the orthodox reading-book of the devout laity,"[91] included newly written passages that explicitly denounced Lollard beliefs.

Plain English scripture manuscripts without illegal Wycliffite/Lollard prefaces or glosses [h] (especially if explicitly marked as dating before 1409) could not be distinguished as Wycliffite texts, and were, on the face of it, legal.

Historian Peter Marshall commented "It seems implausible that so many manuscripts of the Wycliffite bible could have survived…if bishops had really been determined to suppress it in all circumstances.

[i] Manuscripts of Middle English vernacular scriptures had thus been effectively suppressed though not, for private use without Wycliffite paratexts by orthodox readers, actually prohibited, though this was primarily enforced against heretical members of the lower classes, not the aristocracy.

[98] Bishop Reginald Pecock attempted to rebut Lollardy on Wycliffe's own terms, writing in the vernacular and relying on scripture and reason instead of church authority.

Herbert Brook Workman argues that "In later years the existence of Wyclif's version seems to have been forgotten", pointing out that John Wesley incorrectly identified Tyndale's Bible as the first English translation.

[105] In 1850, Forshall and Madden published a four-volume critical edition of the Wycliffian Bibles containing the text of the earlier and later versions in parallel columns.