Wyndham New Yorker Hotel

The setbacks, characterized by architectural writer Anthony W. Robins as "blocky", are ornamented with stone parapets that contain floral and rhombus patterns.

[19][22] All services that used heat, such as cooking equipment, laundry machines, lights, vacuum cleaners, refrigeration, and air conditioning units were supplied by steam from the power plant.

[12] It originally had green-marble paneling; some of Jambor's murals, depicting scenes from New York City's history, were placed on the lobby's north and south walls and on the ceiling.

[77] Hitz hired about fifty of his colleagues from Cincinnati,[28] and he led a $500,000 advertising campaign for the hotel, which at the time was far removed from many of Midtown Manhattan's major attractions.

[24][83] Eight hundred guests made reservations on the first day,[83] many of whom took home souvenirs, prompting Hitz to predict that "the total loss will exceed everything in the past history of hotel openings".

[11] Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the New York Observer said that "actors, celebrities, athletes, politicians, mobsters, the shady and the luminous—the entire Brooklyn Dodgers roster during the glory seasons—would stalk the bars and ballrooms, or romp upstairs".

[111] The chain allocated another $1.5 million to further renovations in June 1954,[112] and it hired the Walter M. Ballard Corporation to convert the hotel's former Empire Tea Room into a restaurant for $175,000.

[129] In anticipation of the opening of the nearby Madison Square Garden arena, New York Towers renovated the New Yorker's two main ballrooms, as well as several smaller public rooms.

[131][132] According to The Wall Street Journal, "other real estate industry sources" indicated that the hotel had lost $4 million since New York Towers bought it.

[135][136] Hilton's public relations director said the chain had reacquired the hotel because the surrounding neighborhood was "coming back to life" with the development of Madison Square Garden and nearby office buildings.

[142] French and Polyclinic filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy that July, allowing the medical center to defer payment of other debts and allocate funding for the New Yorker project.

[148] To reduce its increasing losses, in September 1974, the medical center proposed converting the New Yorker into a homeless shelter for 500 families who had been displaced by emergencies.

[150] French and Polyclinic unsuccessfully attempted to obtain private funding for the hospital from Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, and the city government rejected the shelter plan that November.

[155] A syndicate led by Irving Schatz had acquired a purchase option for the hotel by early 1976; at the time, the New Yorker's only occupant was a ground-level bank branch.

Hilton and Equitable Life allowed Schatz to extend his option, but he could not obtain financing from major savings banks because of the low occupancy rate of a nearby residential development, Manhattan Plaza.

[164] The church requested in 1977 that the New York City Board of Estimate grant a tax exemption to the New Yorker,[165] which had been valued at $11 million the prior year.

[33][174] In May 1994, the Unification Church decided to convert the New Yorker's top eight stories to 250 guestrooms, marketing them to business travelers visiting Javits Center, Penn Station, and Madison Square Garden.

[49] The hotel's clientele largely consisted of tourists from Asia, Europe, and South America, and between 60 and 80 percent of bookings came from wholesalers and travel brokers.

[46] Within two years, the hotel had expanded to 860 rooms; the lowest stories included amenity areas, while the 7th through 17th floors were rented out as commercial office space.

[178] Tourism in New York City had stagnated by early 2001,[179][180] but business was even more negatively impacted by the September 11 attacks,[181][182] which caused the hotel's profit margin to decrease from 25 to 5 percent.

[61] Kevin Smith, the president of the New Yorker Hotel Management Company, considered converting the guestrooms to condominiums but ultimately rejected the plan.

[12][181] Decreased cash flows after the September 11 attacks had prompted the managers to defer renovations, but tourism in New York City had begun to recover by then, and guests were being attracted to newer hotels.

[185] The project would cost $43 million and would include renovating the lobby and meeting rooms, adding a central HVAC system, and refurbishing the upper-story guestrooms.

[29][31] During the renovation, a Fordham University student sued the Unification Church, alleging that her dormitory room (which was not part of the Ramada hotel) had an infestation of bedbugs.

[202][203] In February 2024, the New York County District Attorney's office charged Barreto with fraud after he repeatedly misrepresented himself as the hotel's owner;[205] if Barretto is found guilty, he faces several years in prison.

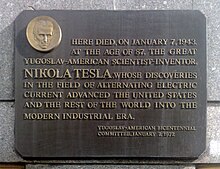

[51] By the 2000s, The New Yorker magazine wrote that Tesla's presence had attracted three kinds of guests, namely "electrical engineers and technology enthusiasts; people interested in U.F.O.s, anti-gravity airships, death-ray weapons, time travel, and telepathic pigeons; Serbs and Croats.

"[51] A reviewer for The Washington Post wrote in 1999 that the hotel was popular among large groups, saying: "If being close to the action is important to you, you won't be unhappy.

"[212] A reviewer for The New York Times praised their room in 2000 as "clean, reasonably sized, and with a lovely vintage tiled prewar bathroom", but criticized the lack of soundproof windows, the crowded lobby, and the gritty character of surrounding neighborhood.

[213] Similarly, an Ottawa Citizen reporter said: "True, the 40-floor art deco hotel has a somewhat dingy exterior, but the location (near Madison Square Garden, Penn Station and Macy's) and the views (maximized by having guest rooms from the 19th floor up) belie the first impression.

[216] Similarly, the U.S. News & World Report said that many guests praised the Wyndham New Yorker's "comfortable accommodations" but criticized the hotel's small rooms and facility fees.