Xanthian Obelisk

The stele lay in plain sight for centuries, though the upper portion was broken off and toppled by an earthquake at some time in antiquity.

Reports of the white marble tombs, which were visible to travellers, attracted the interest of Victorian Age explorers, such as Charles Fellows.

On Saturday, April 14, 1838, Sir Charles Fellows, archaeologist, artist and mountaineer, member of the British Association and man of independent means, arrived in an Arab dhow from Constantinople at the port of Tékrova,[7] site of ancient Phaselis.

Progress along the coast was so slow that Fellows disembarked at Kas, obtained some horses, and proceeded to cross Ak Dağ, perhaps influenced by his interest in mountaineering.

The party cut short its mountain climbing, scrambling down to Patera, to avoid being blown off the slopes by heavy prevailing winds.

[9] He also sought the collaboration of Colonel William Martin Leake, a noted antiquarian and traveller and, with others, including Beaufort, was a founding member of the Royal Geographical Society.

On his return, armed with Beaufort's map, and Leake's directions, Fellows went in search for more Lycian cities, and found eleven more,[11] accounting in all for 24 of Pliny's 36.

He saw Cyclopean walls, gateways, paved roadways, trimmed stone blocks, and above all inscriptions, many in Greek, which he had no trouble reading and translating.

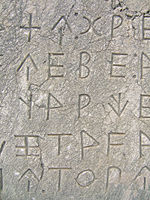

Seeing an inscription in Greek on the northeast side, he realised the importance of the find, but he did not say why, only that it was written in the first person, which "makes the monument itself speak.

There they received a firm commitment from the Sultan:[16] "The Sublime Porte in interested in granting such demands, in consequence of the sincere friendship existing between the two governments."

Much to Fellows' chagrin, he was forced to anchor 50 miles away, but he left a flotilla of small boats under a lieutenant for the transport of the marbles.

The locals were exceedingly hospitable, supplying them with fresh edibles and pertinent advice, until they roasted a boar for dinner one night, after which they were despised for having eaten unclean meat.

The scene for the next few months was frenzied, with Fellows deciding ad hoc what was best to remove, rushing desperately to pry the objects from the earth, while the crews crated them.

Fellows contented himself with taking paper casts of the inscriptions, which, sent to the museum in advance, were the subject of Leake's first analysis and publication.

In all they crated 80 tons of material in 82 cases, which they transported downriver in March, 1842, for loading onto the ship temporarily moored for the purpose.

[22] In a section, Lycian Inscriptions, of Appendix B of his second journal, Fellows includes his transliterations of TAM I 44, with remarks and attempted interpretations.

He quotes a letter from his linguistic assistant, Daniel Sharpe, to whom he had sent copies, mentioning Grotefend's conclusion, based on five previously known inscriptions, that Lycian was Indo-Germanic.