Xu Shen

[2] This education allowed him to hold several government offices at the prefecture level, and ultimately rise to a post in the royal library.

[6] Because knowledge of the Confucian canon was the primary qualification for government office, there was a large upswing in the rate of copying.

[6] During the reign of Emperor Cheng of Han (r. 33 – 7 BCE), however, older manuscripts were discovered in the imperial archives and in the walls of Confucius's family mansion.

Since Han jurisprudence was based on the classics, the interpretation of even a single character could lead to concrete differences in legal opinions.

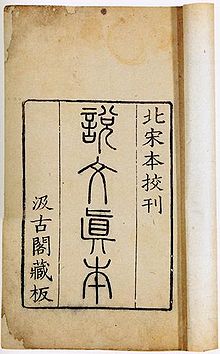

Xu Shen's desire to create an exhaustive reference work resulted in the Shuowen Jiezi (說文解字).

"[1] The uniting principle behind each part of the massive project was, as Xu Shen writes in his postface, "to establish defined categories, [to] correct mistaken concepts, for the benefit of scholars and true interpretation of the spirit of language.

[5][2] Xu intentionally listed headwords in pre-Qin characters in order to provide their earliest possible forms, and thereby allow the most faithful interpretation.

According to legend, Chinese characters were first invented by Cangjie, who was inspired by footprints to create a system of signs that refer to the natural world.

The Song dynasty scholar Zheng Qiao (鄭樵) first presented the interpretation that wen and zi are the difference between non-compound and compound characters.

[7] More recently, other scholars, such as Françoise Bottéro (2002), have argued that the addition of a specifically phonetic element (and thus not simply compounding) marks the principal difference between wen and zi.

[8] From this original binary contrast, Xu Shen formally delineated for the first time the six categories (六書) of Chinese characters.

Xu Shen had to rely on a large body of sources to collect the thousands of characters and variants that appear in the Shuowen.

[2] Given the number of dictionaries and philological works that draw heavily from the Shuowen, Xu Shen has towered over the field of Chinese lexicography, and his influence is still felt today.

Karlgren, for example, disputes Xu Shen's interpretation of 巠 (jing) as depicting a subterranean water channel.