Yangsheng (Daoism)

These include "grain avoidance" diets, in which practitioners consume only qi (breath) instead of solid food, and the ingestion of Daoist alchemical elixirs of life, which were often poisonous and could be fatally toxic.

"[4]Additionally, the Hanyu Da Cidian provides a definition for yàngshēng (養生) in its alternate pronunciation, as seen in Mencius: The concept of yǎng (養, "nourishing") holds a central place in Chinese thought.

Macrobiotics is a convenient term for the belief that it is possible to prepare, with the aid of botanical, zoological, mineralogical and above all chemical, knowledge, drugs or elixirs [dan 丹] which will prolong human life beyond old age [shoulao 壽老], rejuvenating the body and its spiritual parts so that the adept [zhenren 真人] can endure through centuries of longevity [changsheng 長生], finally attaining the status of eternal life and arising with etherealised body a true Immortal [shengxian 升仙].

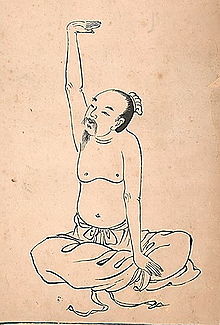

In these medical manuscripts, chángshēng refers to "a somatic form of hygiene centered primarily on controlled breathing in conjunction with yogic exercises," a practice comparable to the classical Greek gymnosophists.

[14] Information about yǎngshēng ("nourishing life") health cultivation was traditionally confined to received texts, including the Chinese classics, until the discovery of second-century BCE medical manuscripts in the 1970s, which expanded this corpus.

Scribes occasionally copied texts onto valuable silk, but more commonly used bamboo and wooden slips, the standard medium for writing documents in China before the widespread introduction of paper during the Eastern Han period (25 BCE–220 CE).

Two of these, He yīnyáng (合陰陽, "Conjoining, Harmony of Yin and Yang") and Tianxia zhidao tán (天下至道谈, "Discussion of the Perfect Way in All Under Heaven"), primarily focus on techniques of sexual cultivation and essence preservation.

Two other texts, Yangshengfang (養生方, "Recipes for Nourishing Life") and Shiwen (十問, "Ten Questions"), similarly contain sections on sexology, but also discuss breathing techniques, food therapies, and medicines.

In the fable about Lord Wenhui (文惠君) coming to understand the Dao while watching Cook Ding (庖丁) cut up an ox, he exclaims how wonderful it is "that skill can attain such heights!"

In one instance, Duke Wei (威公), the younger brother of King Kao of Zhou (r. 440–426 BCE), asks Tian Kaizhi (田開之) what he had learned from his master Zhu Shen (祝腎, "Worthy Invoker").

But it is favored by scholars who channel the vital breath and flex the muscles and joints, men who nourish the physical form [養形] so as to emulate the hoary age of Progenitor P'eng.

To fatten the muscles and skin, to fill the bowel and belly, to satiate the lusts and desires, constitute the branches of nurturing vitality [yangsheng 養生].”[34] The Huangdi Neijing ("Inner Classic of the Yellow Emperor"), dating to approximately the first century BCE, discusses a variety of healing therapies, including medical acupuncture, moxibustion, and herbal medicine, as well as life-nourishing practices such as gymnastics, massage, and dietary regulation.

[35] The Suwen (素問, "Basic Questions") section reflects the early immortality cult and states that ancient sages, who lived in harmony with the Dao, could easily reach a lifespan of one hundred years.

"[36] The astronomer, naturalist, and skeptical philosopher Wang Chong (c. 80 CE) critiques many Daoist beliefs in his Lunheng ("Critical Essays"), particularly the concept of yǎngxìng (養性, "nourishing one's inner nature").

[38]Wang Chong's "Taoist Untruths" (Dàoxū, 道虛) chapter critiques several yǎngshēng practices, particularly the use of so-called "immortality" drugs, bìgǔ (grain avoidance), and Daoist yogic breathing exercises.

… Therefore, when by medicines the various diseases are dispelled, the body made supple, and the vital force prolonged, they merely return to their original state, but it is impossible to add to the number of years, let alone the transition into another existence.

[44] The Han Confucian moralist Xun Yue (148–209) in his Shenjian (申鋻, Extended Reflections) presents a viewpoint similar to Wang Chong's interpretation of cultivating the vital principle.

Methods of waiyang (外養, "outer nourishment") include xianyao (仙藥, "herbs of immortality"), bigu (辟穀, "grain avoidance"), fangzhongshu (房中術, "bedchamber arts"), jinzhou (禁咒, "curses and incantations"), and fulu (符籙, "talismanic registers").

Taking the divine elixir, however, will produce an interminable longevity and make one coeval with sky and earth; it lets one travel up and down in Paradise, riding clouds or driving dragons.

Taking a fundamentally pragmatic approach to yangsheng (nourishing life) and changsheng (longevity) practices, Ge Hong asserts that "the perfection of any one method can only be attained in conjunction with several others.

"[48] The taking of medicines [服藥] may be the first requirement for enjoying Fullness of Life [長生], but the concomitant practice of breath circulation [行氣] greatly enhances speedy attainment of the goal.

Unlike standard medical texts prescribing herbal or acupuncture treatments, the Zhubing yuanhou lun emphasizes yangxing (養性) techniques, including hygienic measures, dietary practices, gymnastics, massage, breathing exercises, and visualization methods.

[56] The renowned physician Sun Simiao dedicated two chapters—Chapter 26, Dietetics, and Chapter 27, Longevity Techniques—of his 652 work, Qianjin fang (千金方, "Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold [Pieces]"), to life-nourishing methods.

[57] Sun Simiao also authored the Sheyang zhenzhong fang (攝養枕中方, "Pillow Book of Methods for Nourishing Life"), which is divided into five sections: prudence, prohibitions, daoyin gymnastics, guiding the qi, and guarding the One (shouyi 守一).

[60] Drawing upon both Shangqing religious texts and major medical sources such as the Huangdi Neijing, the Fuqi jingyi lun organizes various longevity techniques around the central concept of absorbing qi.

In addition to providing practical instructions for specific exercises, the text incorporates theoretical medical knowledge, including discussions on the five orbs (wu zang 五臟), disease healing, and symptom awareness.

Another significant work from this period was Chen Zhi’s (陳直) Yanglao Fengqin Shu (養老奉親書, "Book on Nourishing Old Age and Taking Care of One's Parents"), the first Chinese text dedicated exclusively to geriatrics.

Hu Wenhuan (胡文焕), editor of the 1639 edition of Jiuhuang Bencao ("Famine Relief Herbal"), compiled one of the most comprehensive works on yangsheng, the Shouyang congshu (壽養叢書, "Collectanea on Longevity and Nourishment [of Life]"), around 1596.

For instance, Yang Jizhou's (楊繼洲) extensive 1601 work, Zhenjiu dacheng (針灸大成, "Great Compendium on Acupuncture and Moxibustion"), which remains a classic in traditional Chinese medicine, includes gymnastic exercises designed to regulate the qi meridians.

In the twentieth century, yangsheng evolved in two distinct directions: it influenced the development of weisheng (衛生, "hygiene, health, sanitation") as a modern, Westernized science, while also contributing to the emergence of qigong as a structured practice of breath and energy cultivation.