Ukiyo-e

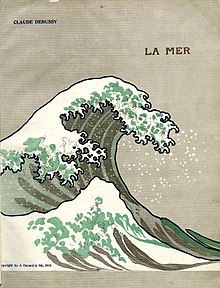

The 19th century also saw the continuation of masters of the ukiyo-e tradition, with the creation of Hokusai's The Great Wave off Kanagawa, one of the most well-known works of Japanese art, and Hiroshige's The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō.

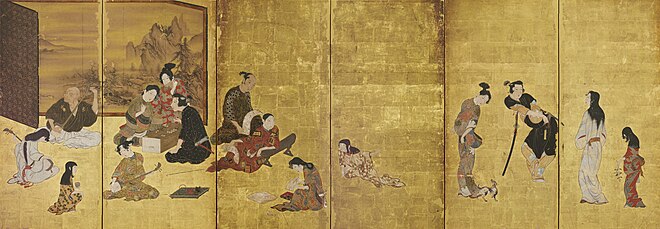

[2] Until the 16th century, the lives of the common people had not been a main subject of painting, and even when they were included, the works were luxury items made for the ruling samurai and rich merchant classes.

[13] The rebuilding of Edo following the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657 occasioned a modernization of the city, and the publication of illustrated printed books flourished in the rapidly urbanizing environment.

Asai Ryōi celebrated this spirit in the novel Ukiyo Monogatari (Tales of the Floating World, c. 1661):[15] [L]iving only for the moment, savouring the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms, and the maple leaves, singing songs, drinking sake, and diverting oneself just in floating, unconcerned by the prospect of imminent poverty, buoyant and carefree, like a gourd carried along with the river current: this is what we call ukiyo.The earliest ukiyo-e artists came from the world of Japanese painting.

Ando and his followers produced a stereotyped female image whose design and pose lent itself to effective mass production,[26] and its popularity created a demand for paintings that other artists and schools took advantage of.

[40] Ukiyo-e reached a peak in the late 18th century with the advent of full-colour prints, developed after Edo returned to prosperity under Tanuma Okitsugu following a long depression.

[48] Sometime-collaborators Koryūsai (1735 – c. 1790) and Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1820) were prominent depicters of women who also moved ukiyo-e away from the dominance of Harunobu's idealism by focusing on contemporary urban fashions and celebrated real-world courtesans and geisha.

His works dispensed with the poetic dreamscapes made by Harunobu, opting instead for realistic depictions of idealized female forms dressed in the latest fashions and posed in scenic locations.

[61] A group of Utagawa-school offenders including Toyokuni had their works repressed in 1801, and Utamaro was imprisoned in 1804 for making prints of 16th-century political and military leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

[63] Utamaro experimented with line, colour, and printing techniques to bring out subtle differences in the features, expressions, and backdrops of subjects from a wide variety of class and background.

[68] Utagawa Toyokuni (1769–1825) produced kabuki portraits in a style Edo townsfolk found more accessible, emphasizing dramatic postures and avoiding Sharaku's realism.

Among his accomplishments are his illustrations of Takizawa Bakin's novel Crescent Moon [ja], his series of sketchbooks, the Hokusai Manga, and his popularization of the landscape genre with Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji,[76] which includes his best-known print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa,[77] one of the most famous works of Japanese art.

[84] He was adept at landscapes and satirical scenes—the latter an area rarely explored in the dictatorial atmosphere of the Edo period; that Kuniyoshia could dare tackle such subjects was a sign of the weakening of the shogunate at the time.

[82] His work was more realistic, subtly coloured, and atmospheric than Hokusai's; nature and the seasons were key elements: mist, rain, snow, and moonlight were prominent parts of his compositions.

[92] Earlier a painter of the Kanō school, in the 1870s Chikanobu (1838–1912) turned to prints, particularly of the imperial family and scenes of Western influence on Japanese life in the Meiji period.

[95] Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg spent a year in the Dutch trading settlement Dejima, near Nagasaki, and was one of the earliest Westerners to collect Japanese prints.

The export of ukiyo-e thereafter slowly grew, and at the beginning of the 19th century Dutch merchant-trader Isaac Titsingh's collection drew the attention of connoisseurs of art in Paris.

[97] Such prints had appeared in Paris from at least the 1830s, and by the 1850s were numerous;[98] reception was mixed, and even when praised ukiyo-e was generally thought inferior to Western works which emphasized mastery of naturalistic perspective and anatomy.

[140] The colourful, ostentatious, and complex patterns, concern with changing fashions, and tense, dynamic poses and compositions in ukiyo-e are in striking contrast with many concepts in traditional Japanese aesthetics.

[147] There was a tendency since early ukiyo-e to pose beauties in what art historian Midori Wakakura [ja] called a "serpentine posture",[h] which involves the subjects' bodies twisting unnaturally while facing behind themselves.

[163] Especially from 1858 to 1862, Yokohama-e prints documented, with various levels of fact and fancy, the growing community of world denizens with whom the Japanese were now coming in contact;[164] triptychs of scenes of Westerners and their technology were particularly popular.

[167] In contrast with previous traditions, ukiyo-e painters favoured bright, sharp colours,[168] and often delineated contours with sumi ink, an effect similar to the linework in prints.

[170] Artists painted with pigments made from mineral or organic substances, such as safflower, ground shells, lead, and cinnabar,[171] and later synthetic dyes imported from the West such as Paris green and Prussian blue.

[179] Prints were made with blocks face up so the printer could vary pressure for different effects, and watch as paper absorbed the water-based sumi ink,[178] applied quickly in even horizontal strokes.

[183] Other effects included burnishing[184] rubbing the paper with agate to brighten colours;[185] varnishing; overprinting; dusting with metal or mica; and sprays to imitate falling snow.

The gasei was most frequently taken from the school the artist belonged to, such as Utagawa or Torii,[194] and the azana normally took a Chinese character from the master's art name—for example, many students of Toyokuni (豊国) took the "kuni" (国) from his name, including Kunisada (国貞) and Kuniyoshi (国芳).

The work did not see print during the Edo era, but circulated in hand-copied editions that were subject to numerous additions and alterations;[205] over 120 variants of the Ukiyo-e Ruikō are known.

[207] Laurence Binyon, the Keeper of Oriental Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, wrote an account in Painting in the Far East in 1908 that was similar to Fenollosa's, but placed Utamaro and Sharaku amongst the masters.

[213] Ukiyo-e scholarship has tended to focus on the cataloguing of artists, an approach that lacks the rigour and originality that has come to be applied to art analysis in other areas.

[249] The first exhibition in Japan of ukiyo-e prints was likely one presented by Kōjirō Matsukata in 1925, who amassed his collection in Paris during World War I and later donated it to the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.