Yanomami

The Yanomami, also spelled Yąnomamö or Yanomama, are a group of approximately 35,000 indigenous people who live in some 200–250 villages in the Amazon rainforest on the border between Venezuela and Brazil.

Other denominations applied to the Yanomami include Waika or Waica, Guiaca, Shiriana, Shirishana, Guaharibo or Guajaribo, Yanoama, Ninam, and Xamatari or Shamatari.

[4] The first report of the Yanomami is from 1654, when a Spanish expedition under Apolinar Diaz de la Fuente visited some Ye'kuana people living on the Padamo River.

Sustained contact with the outside world began in the 1950s with the arrival of members of the New Tribes Mission[7] as well as Catholic missionaries from the Society of Jesus and Salesians of Don Bosco.

CCPY devoted itself to a long national and international campaign to inform and sensitize public opinion and put pressure on the Brazilian government to demarcate an area suited to the needs of the Yanomami.

[10] However, while the constitution of Venezuela recognizes indigenous peoples’ rights to their ancestral domains, few have received official title to their territories and the government has announced it will open up large parts of the Amazon rainforest to legal mining.

The Yanomami can be classified as foraging horticulturalists, depending heavily on rainforest resources; they use slash-and-burn horticulture, grow bananas, gather fruit, and hunt animals and fish.

Men of the Yanomami are said to commit significant intervals of bride service living with their in-laws, and levirate or sororate marriage might be practiced in the event of the death of a spouse.

[20] The body is wrapped in leaves and placed in the forest some distance from the shabono; then after insects have consumed the soft tissue (usually about 30 to 45 days), the bones are collected and cremated.

The garden plots are sectioned off by family, and grow bananas, plantains, sugarcane, mangoes, sweet potatoes, papayas, cassava, maize, and other crops.

[24] In the mornings, while the men are off hunting, the women and young children go off in search of termite nests and other grubs, which will later be roasted at the family hearths.

[25] The women also prepare cassava, shredding the roots and expressing the toxic juice, then roasting the flour to make flat cakes (known in Spanish as casabe), which they cook over a small pile of coals.

[28][better source needed] The Yanomami word for menstruation (roo) translates literally as "squatting" in English, as they use no pads or cloths to absorb the blood.

[30]The mother is notified immediately, and she, along with the elder female friends of the girl, are responsible for disposing of her old cotton garments and replacing them with new ones that symbolize her womanhood and availability for marriage.

[20] The menstrual cycle of Yanomami women does not occur frequently due to constant nursing or child-birthing, and is treated as a very significant occurrence only at this time.

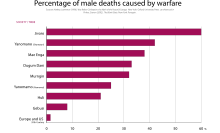

[19]Anthropologists working in the ecologist tradition, such as Marvin Harris, argued that a culture of violence had evolved among the Yanomami through competition resulting from a lack of nutritional resources in their territory.

On September 13, 2021, in her report to the United Nations Human Rights Council, Michelle Bachelet declared that she was "alarmed by recent attacks against members of the Yanomami and Munduruku," in Brazil, "by illegal miners in the Amazon.

Despite the existence of FUNAI, the federal agency representing the rights and interests of indigenous populations, the Yanomami have received little protection from the government against these intrusive forces.

These reserves, however, were small "island" tracts of land lacking consideration for Yanomami lifestyle, trading networks, and trails, with boundaries that were determined solely by the concentration of mineral deposits.

[43] In 1992, the government of Brazil, led by Fernando Collor de Mello, demarcated an indigenous Yanomami area on the recommendations of Brazilian anthropologists and Survival International, a campaign that started in the early 1970s.

Although Yanomami religious tradition prohibits the keeping of any bodily matter after the death of that person, the donors were not warned that blood samples would be kept indefinitely for experimentation.

As of June 2010 these samples were in the process of being removed from storage for shipping to the Amazon, pending the decision as to whom to deliver them to and how to prevent any potential health risks in doing so.

[46] In 2000 Patrick Tierney published Darkness in El Dorado, charging that anthropologists had repeatedly caused harm—and in some cases, death—to members of the Yanomami people whom they had studied in the 1960s.

The book's claims were found to be largely fabricated by Tierney, and the American Anthropological Association in the end voted 846 to 338 in 2005 to rescind a 2002 report on the allegations of misconduct by scholars studying the Yanomami people.

[49] From 1987 to 1990, the Yanomami population was severely affected by malaria, mercury poisoning, malnutrition, and violence due to an influx of garimpeiros searching for gold in their territory.

[60] The Brazilian Ministry of Health declared a national emergency following reports of deaths among Yanomami children due to malnutrition and disease exposure.

Tapeba stated that 20,000 illegal gold miners contaminated the local water supply and fish within and were responsible for causing mercury poisoning.

[63][64] UK-based non-governmental organization Survival International has created global awareness-raising campaigns on the human rights situation of the Yanomami people.

[68] Founder Rüdiger Nehberg crossed the Atlantic Ocean in 1987 in a Pedalo and, together with Christina Haverkamp, in 1992 on a self-made bamboo raft in order to draw attention to the continuing oppression of the Yanomami people.

Additionally, these village schools teach Yanomami about Brazilian society, including money use, good production,[clarification needed] and record-keeping.