Yavapai

[1] The language includes three dialects known as Kwevkepaya (Southern), Tolkepaya (Western), Wipukepa (Verde Valley), and Yavepe (Prescott).

Western archeologists believe the Yavapai derived from Patayan (Hakataya) peoples who migrated east from the Colorado River region to become Upland Yumans.

[8] The first recorded contact with Yavapai was in 1583, when Hopi guides led Spanish explorer Antonio de Espejo,[9] to Jerome Mountain.

[11] To the north and northwest, Wi:pukba and Yavbe' bands had off-and-on relations with the Pai people throughout most of their history.

Though Pai and Yavapai both spoke Upland Yuman dialects, and had a common cultural history, each people had tales of a dispute that separated them from each other.

An estimated quarter of the population died as a result of smallpox in the 17th and 18th centuries, smaller losses than for some tribes, but substantial enough to disrupt their societies.

[16] Following the declaration of war against Mexico in May 1845 and especially after the claim by the US of southwest lands under the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, US military incursions into Yavapai territory greatly increased.

The last big battle between the Colorado–Gila River alliances took place in August 1857, when about 100 Yavapai, Quechan, and Mohave warriors attacked a settlement of Maricopa near Pima Butte.

A group of Akimel O'odham, supplied with guns and horses from US troops, arrived and routed the remaining Mohave and Quechans.

The son, Lorenzo, was left for dead but survived, while sisters Olive Oatman and Mary Ann were later sold to Mojaves as slaves.

At the time, the Yavapai were considered a band of the Western Apache people due to their close relationship with tribes such as the Tonto and Pinal.

[22][23] When in early 1863, the Walker Party discovered gold in Lynx Creek (near present-day Prescott, Arizona), it set off a chain of events that would have White settlements along the Hassayampa and Agua Fria Rivers, the nearby valleys, as well as in Prescott, and Fort Whipple would be built, all by the end of the year, and all in traditional Yavapai territory.

Some communities supplemented this diet with small-scale cultivation of the "three sisters" (maize, squash, and beans) in fertile streambeds.

In turn, Tolkepaya often traded items such as animal skins, baskets, and agave to Quechan groups for food.

The Yavapai built brush shelter dwellings called Wa'm bu nya:va (Wom-boo-nya-va).

During winter months, closed huts (called uwas) would be built of ocotillo branches or other wood and covered with animal skins, grasses, bark, and/or dirt.

In the Colorado River area, Tolkepaya built Uwađ a'mađva, a rectangular hut, that had dirt piled up against its sides for insulation, and a flat roof.

[29] The Yavapai main sociopolitical organization were local groups of extended families, which were identified with certain geographic regions in which they resided.

Near Fish Creek, Arizona, was Ananyiké (Quail's Roost), a Guwevkabaya summer camp that supported upwards of 100 people at a time.

Called bakwauu ("person who talks"), they would settle disputes within the camp and advise others on the selection of campsites, work ethics, and food production.

Historically they were four separate autonomous bands, connected through kinship and shared cultures and language, which were in turn composed of clans.

[citation needed] The Tolkepaya lived in the western Yavapai territory along the Hassayampa River in southwestern Arizona.

[33] The Wi:pukba ("People from the Foot of the Red Rock") and Guwevkabaya lived alongside the Tonto Apache of central and western Arizona.

Therefore, the enemy Navajo to the north called both, the Tonto Apache and their allies, the Yavapai, Dilzhʼíʼ dinéʼiʼ – "People with high-pitched voices."

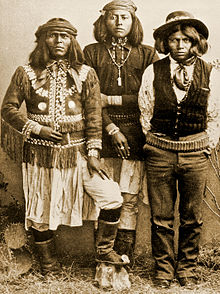

The Yavapai women were described as stouter and having "handsomer" faces than the Yuma, in a historic Smithsonian Institution report.

[37] Tourism contributes greatly to the economy of the tribe, due largely to the presence of many preserved sites, including the Montezuma Castle National Monument.

The Yavapai–Apache Nation is the amalgamation of two historically distinct Tribes both of whom occupied the Upper Verde prior to European arrival.

The Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation is located within Maricopa County approximately 20 miles northeast of Phoenix.

[42] Responding to growth in the Phoenix area, in the early 1970s Arizonan officials proposed to build a dam at the point where the Verde and Salt rivers meet.

In 1981, after much petitioning of the US government, and a three-day march by approximately 100 Yavapai,[43] the plan to build the dam was withdrawn.