Ancestral Puebloans

The current agreement, based on terminology defined by the Pecos Classification, suggests their emergence around the 12th century BCE, during the archaeologically designated Early Basketmaker II Era.

Beginning with the earliest explorations and excavations, researchers identified Ancestral Puebloans as the forerunners of contemporary Pueblo peoples although specific site to modern group connections are unclear.

Structures and other evidence of Ancestral Puebloan culture have been found extending east onto the American Great Plains, in areas near the Cimarron and Pecos Rivers[13] and in the Galisteo Basin.

Extensive horizontal mesas are capped by sedimentary formations and support woodlands of junipers, pinyon, and ponderosa pines, each favoring different elevations.

Where sandstone layers overlay shale, snow melt could accumulate and create seeps and springs, which the Ancestral Puebloans used as water sources.

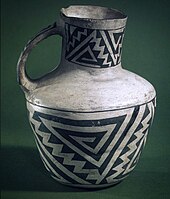

In the northern portion of the Ancestral Pueblo lands, from about 500 to 1300 CE, the pottery styles commonly had black-painted designs on white or light gray backgrounds.

According to archaeologists Patricia Crown and Steadman Upham, the appearance of the bright colors on Salado Polychromes in the 14th century may reflect religious or political alliances on a regional level.

Late 14th- and 15th-century pottery from central Arizona, widely traded in the region, has colors and designs which may derive from earlier ware by both Ancestral Pueblo and Mogollon peoples.

The so-called "Holy Ghost panel" in the Horseshoe Canyon is considered to be one of the earliest uses of graphical perspective where the largest figure appears to take on a three-dimensional representation.

Recent archaeological evidence has established that in at least one great house, Pueblo Bonito, the elite family whose burials associate them with the site practiced matrilineal succession.

Room 33 in Pueblo Bonito, the richest burial ever excavated in the Southwest, served as a crypt for one powerful lineage, traced through the female line, for approximately 330 years.

These complexes hosted cultural and civic events and infrastructure that supported a vast outlying region hundreds of miles away linked by transportation roadways.

Many Chacoan buildings may have been aligned to capture the solar and lunar cycles,[22] requiring generations of astronomical observations and centuries of skillfully coordinated construction.

Archaeologists have found musical instruments, jewelry, ceramics, and ceremonial items, indicating people in the Great Houses were elite, wealthier families.

[citation needed] Archaeological interpretations of the Chaco road system are divided between an economic purpose and a symbolic, ideological or religious role.

Items such as macaws, turquoise and seashells, which are not part of this environment, and imported vessels distinguished by design, prove that the Chaco traded with distant regions.

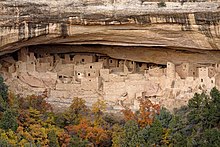

Unlike earlier structures and villages atop mesas, this was a regional 13th-century trend of gathering the growing populations into close, defensible quarters.

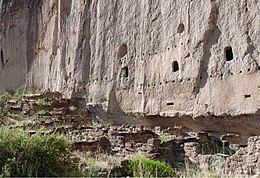

This area included common Pueblo architectural forms, such as kivas, towers, and pit-houses, but the space restrictions of these alcoves resulted in far denser populations.

[28] Not all the people in the region lived in cliff dwellings; many colonized the canyon rims and slopes in multifamily structures that grew to unprecedented size as populations swelled.

[33] Current scholarly consensus is that Ancestral Puebloans responded to pressure from Numic-speaking peoples moving onto the Colorado Plateau, as well as climate change that resulted in agricultural failures.

Archaeologist Timothy A. Kohler excavated large Pueblo I sites near Dolores, Colorado, and discovered that they were established during periods of above-average rainfall.

Confirming evidence dated between 1150 and 1350 has been found in excavations of the western regions of the Mississippi Valley, which show long-lasting patterns of warmer, wetter winters and cooler, drier summers.

Southwest farmers developed irrigation techniques appropriate to seasonal rainfall, including soil and water control features such as check dams and terraces.

Possibly, the dismantling of their religious structures was an effort to symbolically undo the changes they believed they caused due to their abuse of their spiritual power, and thus make amends with nature.

Near Kayenta, Arizona, Jonathan Haas of the Field Museum in Chicago has been studying a group of Ancestral Puebloan villages that relocated from the canyons to the high mesa tops during the late 13th century.

Others suggest that more developed villages, such as that at Chaco Canyon, exhausted their environments, resulting in widespread deforestation and eventually the fall of their civilization through warfare over depleted resources.

A 1997 excavation at Cowboy Wash near Dolores, Colorado found remains of at least 24 human skeletons that showed evidence of violence and dismemberment, with strong indications of cannibalism.

[41] In a 2010 paper, Potter and Chuipka argued that evidence at Sacred Ridge site, near Durango, Colorado, is best interpreted as warfare related to competition and ethnic cleansing.

[39][43][44] Suggested alternatives include: a community suffering the pressure of starvation or extreme social stress, dismemberment and cannibalism as religious ritual or in response to religious conflict, the influx of outsiders seeking to drive out a settled agricultural community via calculated atrocity, or an invasion of a settled region by nomadic raiders who practiced cannibalism.

Current opinion holds that the closer cultural similarity between the Mogollon and Ancestral Puebloans, and their greater differences from the Hohokam and Patayan, is due to both the geography and the variety of climate zones in the Southwest.