Yermak Timofeyevich

[6] However, his life and conquests had a profound influence on Siberian relations, sparking Russian interest in the region and establishing the Tsardom of Russia as an imperial power east of the Urals.

[13][14] The combination of forgotten details over time and the embellishment or omission of facts in order for Yermak to be accepted as a saint suggests that the Sinodik could be erroneous.

[10] While the sources that exist on Yermak are fallible, those accounts, along with folklore and legend, are all that historians have to base their knowledge on; therefore, they are widely accepted and considered to reflect the truth.

This chronicle, compiled by a Tobolsk coachman in 1760 – long after Yermak's death – was never published in full, but, in 1894, historian Aleksandr Alekseyevich Dmitriyev concluded it probably represents a copy or paraphrase of an authentic 17th-century document.

[16][17] Prior to his conquest of Siberia, Yermak's combat experience consisted of leading a Cossack detachment for the tsar in the Livonian War of 1558–83 and plundering merchant ships.

[3][11][18] Based on legends and folk songs, for years, Yermak had been involved in robbing and plundering on the Volga with the hetman Ivan Kolzo and four other Cossack leaders.

Ivan the Terrible had tremendous trust in the entrepreneurial prowess of the Stroganov family and granted them the province of Perm as a financial investment which would be sure to benefit Russia in the future.

[27] However, the tsar soon changed his mind and told the Stroganovs to retract from Siberia, fearing that Russia did not have the resources or manpower to topple Kuchum Khan's empire.

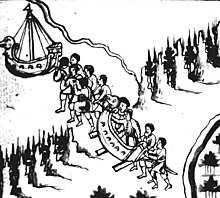

According to Russian history specialist W. Bruce Lincoln, the Tatars' "bows, arrows, and spears" went up against Yermak's team's "matchlock muskets, sabers, pikes, and several small cannons.

Upon their failure to return, Yermak left the city to investigate, eventually finding that Mahmet-kul had recovered from their earlier battle and was responsible for the Cossacks' murder.

[47] To the detriment of Moscow's interests, the Livonian War had just been ended and Ivan had begun receiving reports of local tribesman conducting raids in Perm,[47] putting him in a foul mood.

Upon reading the news born by Kolzo concerning the extension of his dominion, Ivan became overjoyed, immediately pardoning the Cossacks and proclaiming Yermak to be a hero of the first degree.

[51] Ivan then had many gifts prepared for Yermak, including his personal fur mantle, a goblet, two suits of armor emblazoned with bronze double-headed eagles, and money.

[59] Sensing Yermak's waning power, the tribes previously under his control revolted,[54] and Qashliq soon came under siege by a collective army of Tatars, Voguls, and Ostyaks.

[55] Whether because of an ongoing storm[55] or because the men were tired from rowing upstream,[67] Yermak's force stopped on a small island formed by two branches of the Irtysh and set up camp on the night of August 4–5, 1584.

[55] Easily recognizable by the eagle on his armor, Yermak's corpse was stripped and hung on a frame made out of six poles, where for six weeks archers used his body for target practice.

[71] The original band of men had dwindled to 150 fighters,[72] and command now fell to Glukhoff, the leader of the initial group of reinforcements that the tsar had delivered to Yermak.

Instead, in a culmination of the events immediately following Yermak's fatal plunge, they founded a new settlement in 1587 on the site of what would become Tobolsk, a comfortable twelve miles from Qashliq.

Soon after Yermak and his initial band set out for Siberia, merchants and peasants followed in their wake, hoping to harness some of the fur riches that abounded in the land.

[74] This trend grew exponentially after Yermak's death, as his legend spread through the domain rapidly and, with it, the news of a land rich in furs and vulnerable to Russian influence.

[76] Yermak had set a precedent of Cossack involvement in Siberian expansion, and the exploration and conquests of these men were responsible for many of the additions to the Russian empire in the east.

Indeed, within the first half of the century the fort of Yeniseysk was established in 1619, the city of Yakutsk founded in 1632, and the important feat of reaching the Sea of Okhotsk on the Pacific coast in 1639.

[72] Throughout these campaigns, Yermak's influence was undeniable, as the pace he had established for achievement in his relatively short time in Siberia heralded a new age of Russian pioneering.

The top priority was the repelling of the Tatar hordes, and, as shown by Ivan's letter to the Strogonovs, the central government rarely involved itself unless the tribes succeeded in entering Russian territory.

[citation needed] Future explorers would also take notice of Yermak's strategy in approaching the Siberian lands, which, unlike those in many other colonization attempts, already had an established imperial power.

Yermak's unique strength was thus in recognizing the bigger picture and playing it to his advantage, first identifying and then executing quick, efficient ways to establish influence in the region.

[75] Yermak's call for aid thus spawned a new type of Cossack which, by virtue of its link to the government, would enjoy significant favor from future Russian rulers.

The movie tells the story of a pianist named Andrei who moves to Siberia to work at a paper-processing plant after being wounded in World War II and losing his faith in music.

Fire turns into lightning, and then the rain begins: the conquest of the elements is complete, as nature bows down in the face of Russian strength, and Siberia is conquered.

[citation needed] In 1996, directors Vladimir Krasnopolsky and Valeri Uskov produced the film Yermak, a historical drama about the conquest of Siberia which starred Viktor Stepanov, Irina Alfyorova, and Nikita Dzhigurda.