I Ching

Over the course of the Warring States and early imperial periods (500–200 BC), it transformed into a cosmological text with a series of philosophical commentaries known as the Ten Wings.

[10] According to the canonical Great Commentary, Fuxi observed the patterns of the world and created the eight trigrams (八卦; bāguà), "in order to become thoroughly conversant with the numinous and bright and to classify the myriad things".

[15] The basic unit of the Zhou yi is the hexagram (卦 guà), a figure composed of six stacked horizontal lines (爻 yáo).

The Great Commentary contains a late classic description of a process where various numerological operations are performed on a bundle of 50 stalks, leaving remainders of 6 to 9.

[30] The most common form of divination with the I Ching in use today is a reconstruction of the method described in these histories, in the 300 BC Great Commentary, and later in the Huainanzi and the Lunheng.

[39] Regardless of their historical relation to the text, the philosophical depth of the Ten Wings made the I Ching a perfect fit to Han period Confucian scholarship.

[40] The inclusion of the Ten Wings reflects a widespread recognition in ancient China, found in the Zuo zhuan and other pre-Han texts, that the I Ching was a rich moral and symbolic document useful for more than professional divination.

[45] Throughout the Ten Wings, there are passages that seem to purposefully increase the ambiguity of the base text, pointing to a recognition of multiple layers of symbolism.

[46] The Great Commentary associates knowledge of the I Ching with the ability to "delight in Heaven and understand fate;" the sage who reads it will see cosmological patterns and not despair in mere material difficulties.

[49] Although it rested on historically shaky grounds, the association of the I Ching with Confucius gave weight to the text and was taken as an article of faith throughout the Han and Tang dynasties.

An ancient commentary on the Zhou yi found at Mawangdui portrays Confucius as endorsing it as a source of wisdom first and an imperfect divination text second.

[51] However, since the Ten Wings became canonized by Emperor Wu of Han together with the original I Ching as the Zhou Yi, it can be attributed to the positions of influence from the Confucians in the government.

[52] Furthermore, the Ten Wings tends to use diction and phrases such as "the master said", which was previously commonly seen in the Analects, thereby implying the heavy involvement of Confucians in its creation as well as institutionalization.

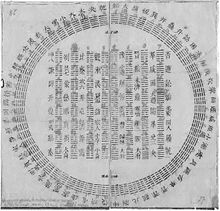

Different constructions of three yin and yang lines lead to eight trigrams (八卦) namely, Qian (乾, ☰), Dui (兌, ☱), Li (離, ☲), Zhen (震, ☳), Xun (巽, ☴), Kan (坎, ☵), Gen (艮, ☶), and Kun (坤, ☷).

[57] In East Asia, it is a foundational text for the Confucian and Daoist philosophical traditions, while in the West, it attracted the attention of Enlightenment intellectuals and prominent literary and cultural figures.

A century later Han Kangbo added commentaries on the Ten Wings to Wang Bi's book, creating a text called the Zhouyi zhu.

[64] By the 11th century, the I Ching was being read as a work of intricate philosophy, as a jumping-off point for examining great metaphysical questions and ethical issues.

[66] The contemporary scholar Shao Yong rearranged the hexagrams in a format that resembles modern binary numbers, although he did not intend his arrangement to be used mathematically.

He developed a synthesis of the two, arguing that the text was primarily a work of divination that could be used in the process of moral self-cultivation, or what the ancients called "rectification of the mind" in the Great Learning.

Zhu Xi's reconstruction of I Ching yarrow stalk divination, based in part on the Great Commentary account, became the standard form and is still in use today.

[69] Qing dynasty scholars focused more intently on understanding pre-classical grammar, assisting the development of new philological approaches in the modern period.

In 1557, the Korean Neo-Confucianist philosopher Yi Hwang produced one of the most influential I Ching studies of the early modern era, claiming that the spirit was a principle (li) and not a material force (qi).

[72] In medieval Japan, secret teachings on the I Ching—known in Japanese as the Eki Kyō (易経)—were publicized by Rinzai Zen master Kokan Shiren and the Shintoist Yoshida Kanetomo during the Kamakura era.

[75] In the early Edo period, Japanese writers such as Itō Jinsai, Kumazawa Banzan, and Nakae Tōju ranked the I Ching the greatest of the Confucian classics.

[79] This was criticized by Georg Friedrich Hegel, who proclaimed that binary system and Chinese characters were "empty forms" that could not articulate spoken words with the clarity of the Western alphabet.

[80] In their commentary, I Ching hexagrams and Chinese characters were conflated into a single foreign idea, sparking a dialogue on Western philosophical questions such as universality and the nature of communication.

[82] The sinologist Joseph Needham took the opposite opinion, arguing that the I Ching had actually impeded scientific development by incorporating all physical knowledge into its metaphysics.

[83] The psychologist Carl Jung took interest in the possible universal nature of the imagery of the I Ching, and he introduced an influential German translation by Richard Wilhelm by discussing his theories of archetypes and synchronicity.

"[85] The book had a notable impact on the 1960s counterculture and on 20th century cultural figures such as Philip K. Dick, John Cage, Jorge Luis Borges, Terence McKenna and Hermann Hesse.

Joni Mitchell references the six yang hexagram in "Amelia", a song on the album Hejira, where she describes the image of "...six jet planes leaving six white vapor trails across the bleak terrain...".

) of

zhēn

(

貞

) 'to divine'

) of

zhēn

(

貞

) 'to divine'