Yinglong

This legendary creature's name combines yìng 應 "respond; correspond; answer; reply; agree; comply; consent; promise; adapt; apply" and lóng 龍 "Chinese dragon".

The examples below, limited to books with English translations, are roughly arranged in chronological order, although some heterogeneous texts have uncertain dates of composition.

The Heavenly Questions section (3, 天問) asks about Yinglong, in context with Zhulong 燭龍 "Torch Dragon".

Tianwen, which Hawkes characterizes as "a shamanistic catechism consisting of questions about cosmological, astronomical, mythological and historical matters", and "is written in an archaic language to be found nowhere else in the Chu anthology" excepting "one or two short passages" in the Li Sao section.

[2]The (early second century CE) Chuci commentary of Wang Yi 王逸 answers that Yinglong drew lines on the ground to show Yu where to dig drainage and irrigation canals.

The "Responding Dragon" is connected with two deities who rebelled against the Yellow Emperor: the war-god and rain-god Chiyou 蚩尤 "Jest Much" and the giant Kua Fu 夸父 "Boast Father".

"[4] "The Classic of the Great Wilderness: The North" (17, 大荒北經) mentions Yinglong in two myths about killing Kua Fu "Boast Father".

The first version says Yinglong killed him in punishment for drinking rivers and creating droughts while chasing the sun.

[5]The second mythic version says the Yellow Emperor's daughter Ba 魃 "Droughtghoul" killed Chiyou "Jest Much" after Yinglong failed.

[6]Based on textual history of Yinglong, Chiyou, Kua Fu, and related legends, Bernhard Karlgren concludes that "all these nature myths are purely Han-time lore, and there is no trace of them in pre-Han sources", with two exceptions.

"sensation and response") "resonance; reaction; interaction; influence; induction", which Charles Le Blanc posits as the Huannanzi text's central and pivotal idea.

[9] "Forms of Earth" (4, 墬形訓) explains how animal evolution originated through dragons, with Yinglong as the progenitor of quadrupeds.

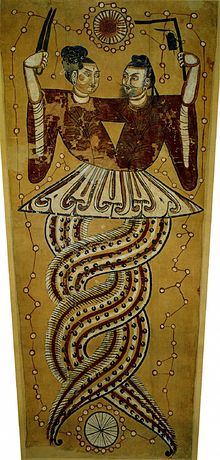

[12] "Peering into the Obscure" (6, 覽冥訓) describes Fuxi and Nüwa being transported by yinglong 應龍 and qingqiu 青虯 "green qiu-dragons", while accompanied by baichi 白螭 "white chi-dragons" and benshe 奔蛇 "speeding snakes".

Yellow clouds hung inter-woven (to form a coverlet over the chariot) and they (the whole retinue) were preceded by white serpents and followed by speeding snakes.

"The t'eng snake springs up into the mist; the flying ying dragon ascends into the sky mounting the clouds; a monkey is nimble in the trees and a fish is agile in the water."

Ames compares the Hanfeizi attribution of this yinglong and tengshe metaphor to the Legalist philosopher Shen Dao.

But when the clouds dissipate and the mists clear, the dragon and the snake become the same as the earthworm and the large-winged black ant because they have lost that on which they ride.

[16] The early sixth century CE Shuyiji 述異記 "Records of Strange Things" lists yinglong as a 1000-year-old dragon.

Visser mentions that texts like the Daoist Liexian Zhuan often record "flying dragons or ying-lung drawing the cars of gods or holy men".

[19] Carr compares pairs of Yinglong with motifs on Chinese bronzes showing two symmetrical dragons intertwined like Fuxi and Nüwa.

Carr cites Chen Mengjia's hypothesis, based on studies of Shang dynasty oracle bones, that Yinglong was originally associated with the niqiu 泥鰍 "loach".

[24] Yinglong representations were anciently used in rain-magic ceremonies, where Eberhard says "the most important animal is always a dragon made of clay".