Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor personally led five campaigns into Mongolia, and the decision to move the capital from Nanjing to Beijing was motivated by the need to keep a close eye on the restless northern neighbors.

The following year, a Ming army led by Lan Yu made a foray into eastern Mongolia and defeated the Mongol khan Tögüs Temür, capturing many prisoners and horses, but both generals were accused of mistreating captives and misappropriating booty, which was reported to the emperor by the prince.

[41] In his letters and statements, he repeatedly asserted that he had no desire for the throne, but as the eldest living son of the deceased emperor, he felt a duty to restore the laws and order that had been dismantled by the new government.

Despite the Nanjing government's larger number of armies and greater material resources, Zhu Di's soldiers were of higher quality and he possessed a strong Mongol cavalry.

[43] In September 1399, a government army of 130,000 soldiers, led by the experienced veteran general Geng Bingwen, marched towards Zhending, a city located southwest of Beiping, but by the end of the month, they were defeated.

In October 1402, he appointed two dukes (gong; 公)—Qiu Fu and Zhu Neng (朱能), thirteen marquises (hou; 侯), and nine counts (bo; 伯).

Among these appointments were one duke and three counts from the dignitaries who had defected to his side before the fall of Nanjing—Li Jinglong, Chen Xuan (陳瑄), Ru Chang (茹瑺), and Wang Zuo (王佐).

[59] The Grand Secretariat was established in August 1402, when the emperor began to address current administrative issues during a working dinner with Huang Huai and Xie Jin after the evening audience.

[65] Other notable ministers who served for many years included Jian Yi (蹇義), Song Li (宋禮), Liu Quan (劉觀), and Zhao Hong, who held various ministerial positions.

[70] Huang Huai (from 1414 until the end of the Yongle Emperor's reign) and Yang Shiqi (briefly in 1414), both accused of not observing the ceremony, also faced imprisonment due to their support of the crown prince and resulting enmity with Zhu Gaoxu.

[84] In response, the government attempted to resettle people from the densely populated south to the north, but the southerners struggled to adapt to the harsh northern climate and many returned to their homes.

[89] As a result of these financial challenges, the state's reserves, which were typically equivalent to one year's income during the Ming period, reached a record low under the Yongle Emperor's rule.

Its strategic location in the middle of the canal network south of the Yangtze (which was reconstructed after 1403)[117] allowed the city to regain its status as a major commercial hub and experience a return to prosperity after being deprived of it during the reign of the Hongwu Emperor.

In Huguang, a large-scale construction project was undertaken by the Yongle Emperor, who employed twenty thousand workers over a period of twelve years to build a complex of Taoist temples and monasteries on the Wudang Mountains.

[120] The main objective of this project was to gain popularity among the people and to erase any negative impressions left by the previous emperor's overthrow and harsh treatment of secret societies.

[121] This impressive structure, made entirely of white "porcelain" bricks, stood at over 70 meters tall[xxii] and served as a prominent landmark in Nanjing until its destruction during the Taiping Rebellion.

[125] In 1414, he tasked scholars from the Hanlin Academy with creating a comprehensive collection of commentaries on the Four Books and Five Classics by Zhu Xi and other prominent Confucian thinkers of his school.

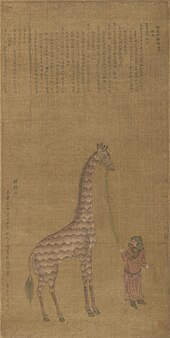

In an effort to incorporate countries from around the world into the tributary system of subordination to the Ming dynasty, the emperor utilized a combination of military force, diplomatic contacts, trade exchange, and the spread of Chinese culture.

In this system, the Mongols would provide horses and other domestic animals in exchange for paper money, silver, silk, cloth, and titles and ranks for their leaders, but the Ming government placed restrictions on the amount of trade allowed.

In March 1410, he led an army of hundreds of thousands from Beijing[xxiv] and after a three-month campaign, he was able to defeat Öljei Temür Khan Bunyashiri and the Mongol chingsang Arughtai.

[164] Among the Jurchens living in Manchuria, the Ming government aimed to maintain peace on the borders, counter Korean influence, acquire horses and other local products such as furs, and promote Chinese culture and values among them.

These demands included providing horses and oxen for military purposes,[xxv] bronze Buddha statues, relics, paper for printing Buddhist literature, and even sending girls to serve in the imperial harem.

[178] This included important countries such as Champa, Malacca, Ayutthaya (in present-day Thailand), Majapahit (centered in Java), Samudera in Sumatra, Khmer, and Brunei, all of which paid tribute to the Yongle Emperor.

[179] The Ming government showed a strong interest in trade and left a lasting impression of their naval power in Southeast Asia, although their focus shifted to northern affairs after 1413.

[140] Champa was a significant ally against insurgents in Jiaozhi, as they were traditional enemies, but relations cooled in 1414 when the Yongle Emperor refused to return territories previously conquered by the Viets.

Ming envoys then coerced the Javanese king into paying an indemnity of 60,000 liang (2,238 kg) of gold, threatening that Java would suffer the same fate as Đại Việt if they did not comply.

[185] In 1405, the Yongle Emperor appointed his favorite commander, the eunuch Zheng He, as admiral of a fleet with the purpose of expanding China's influence and collecting tribute from various nations.

[103] While official annals do not provide a specific cause of death, private records suggest that the emperor suffered from multiple strokes in his final years, with the last one ultimately proving to be fatal.

In 1538, the Jiajing Emperor changed the temple name to Chengzu (Accomplished Progenitor) in order to strengthen the legitimacy of his decision to elevate his father to imperial status after his death.

[198] Modern historians, such as Chan Hok-lam and Wang Yuan-Kang,[90][199] argue that the Yongle Emperor's desire for a unified China and domination over the world ultimately led to decisions that proved problematic in the long run.