Young's interference experiment

During this period, many scientists proposed a wave theory of light based on experimental observations, including Robert Hooke, Christiaan Huygens and Leonhard Euler.

[3] This theory held sway until the beginning of the nineteenth century despite the fact that many phenomena, including diffraction effects at edges or in narrow apertures, colours in thin films and insect wings, and the apparent failure of light particles to crash into one another when two light beams crossed, could not be adequately explained by the corpuscular theory which, nonetheless, had many eminent supporters, including Pierre-Simon Laplace and Jean-Baptiste Biot.

While studying medicine at Göttingen in the 1790s, Young wrote a thesis on the physical and mathematical properties of sound[4] and in 1800, he presented a paper to the Royal Society (written in 1799) where he argued that light was also a wave motion.

He believed that a wave model could much better explain many aspects of light propagation than the corpuscular model: A very extensive class of phenomena leads us still more directly to the same conclusion; they consist chiefly of the production of colours by means of transparent plates, and by diffraction or inflection, none of which have been explained upon the supposition of emanation, in a manner sufficiently minute or comprehensive to satisfy the most candid even of the advocates for the projectile system; while on the other hand all of them may be at once understood, from the effect of the interference of double lights, in a manner nearly similar to that which constitutes in sound the sensation of a beat, when two strings forming an imperfect unison, are heard to vibrate together.

[5]In 1801, Young presented a famous paper to the Royal Society entitled "On the Theory of Light and Colours"[7] which describes various interference phenomena.

[6][8][9] He also mentions the possibility of passing light through two slits in his description of the experiment: Supposing the light of any given colour to consist of undulations of a given breadth, or of a given frequency, it follows that these undulations must be liable to those effects which we have already examined in the case of the waves of water and the pulses of sound.

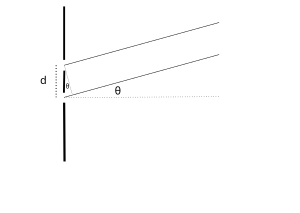

In order that the effects of two portions of light may be thus combined, it is necessary that they be derived from the same origin, and that they arrive at the same point by different paths, in directions not much deviating from each other.

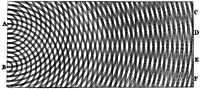

This deviation may be produced in one or both of the portions by diffraction, by reflection, by refraction, or by any of these effects combined; but the simplest case appears to be, when a beam of homogeneous light falls on a screen in which there are two very small holes or slits, which may be considered as centres of divergence, from whence the light is diffracted in every direction.

The combination of two portions of white or mixed light, when viewed at a great distance, exhibits a few white and black stripes, corresponding to this interval: although, upon closer inspection, the distinct effects of an infinite number of stripes of different breadths appear to be compounded together, so as to produce a beautiful diversity of tints, passing by degrees into each other.

When the path difference is equal to an integer number of wavelengths, the two waves add together to give a maximum in the brightness, whereas when the path difference is equal to half a wavelength, or one and a half etc., then the two waves cancel, and the intensity is at a minimum.

It can be seen that the spacing of the fringes depends on the wavelength, the separation of the holes, and the distance between the slits and the observation plane, as noted by Young.

This expression applies when the light source has a single wavelength, whereas Young used sunlight, and was therefore looking at white-light fringes which he describes above.

The anonymous author (later revealed to be Henry Brougham, a founder of the Edinburgh Review) succeeded in undermining Young's credibility among the reading public sufficiently that a publisher who had committed to publishing Young's Royal Institution lectures backed out of the deal.