Photoelectric effect

[2] Study of the photoelectric effect led to important steps in understanding the quantum nature of light and electrons and influenced the formation of the concept of wave–particle duality.

This is because the process produces a charge imbalance which, if not neutralized by current flow, results in the increasing potential barrier until the emission completely ceases.

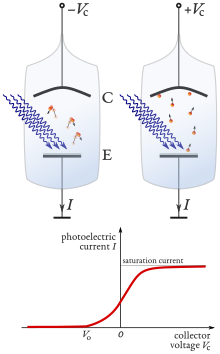

When no current is observed through the tube, the negative voltage has reached the value that is high enough to slow down and stop the most energetic photoelectrons of kinetic energy Kmax.

Angular distribution of the photoelectrons is highly dependent on polarization (the direction of the electric field) of the incident light, as well as the emitting material's quantum properties such as atomic and molecular orbital symmetries and the electronic band structure of crystalline solids.

Einstein's formula, however simple, explained all the phenomenology of the photoelectric effect, and had far-reaching consequences in the development of quantum mechanics.

Electrons that are bound in atoms, molecules and solids each occupy distinct states of well-defined binding energies.

[21] Though not equivalent to the photoelectric effect, his work on photovoltaics was instrumental in showing a strong relationship between light and electronic properties of materials.

In 1873, Willoughby Smith discovered photoconductivity in selenium while testing the metal for its high resistance properties in conjunction with his work involving submarine telegraph cables.

[23][24]: 458 They arranged metals with respect to their power of discharging negative electricity: rubidium, potassium, alloy of potassium and sodium, sodium, lithium, magnesium, thallium and zinc; for copper, platinum, lead, iron, cadmium, carbon, and mercury the effects with ordinary light were too small to be measurable.

A glass panel placed between the source of electromagnetic waves and the receiver absorbed ultraviolet radiation that assisted the electrons in jumping across the gap.

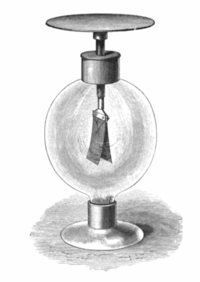

From these observations he concluded that some negatively charged particles were emitted by the zinc plate when exposed to ultraviolet light.

According to Hallwachs, ozone played an important part in the phenomenon,[34] and the emission was influenced by oxidation, humidity, and the degree of polishing of the surface.

[citation needed] In the period from 1888 until 1891, a detailed analysis of the photoeffect was performed by Aleksandr Stoletov with results reported in six publications.

[citation needed] During the years 1886–1902, Wilhelm Hallwachs and Philipp Lenard investigated the phenomenon of photoelectric emission in detail.

Lenard observed that a current flows through an evacuated glass tube enclosing two electrodes when ultraviolet radiation falls on one of them.

[5][39] This appeared to be at odds with Maxwell's wave theory of light, which predicted that the electron energy would be proportional to the intensity of the radiation.

Lenard observed the variation in electron energy with light frequency using a powerful electric arc lamp which enabled him to investigate large changes in intensity.

In 1905, Albert Einstein published a paper advancing the hypothesis that light energy is carried in discrete quantized packets to explain experimental data from the photoelectric effect.

A photon above a threshold frequency has the required energy to eject a single electron, creating the observed effect.

This was a theoretical leap, but the concept was strongly resisted at first because it contradicted the wave theory of light that followed naturally from James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism, and more generally, the assumption of infinite divisibility of energy in physical systems.

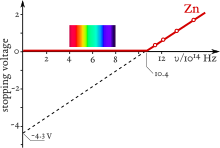

Einstein's work predicted that the energy of individual ejected electrons increases linearly with the frequency of the light.

The effect was impossible to understand in terms of the classical wave description of light,[50][51][52] as the energy of the emitted electrons did not depend on the intensity of the incident radiation.

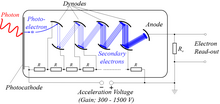

By means of a series of electrodes (dynodes) at ever-higher potentials, these electrons are accelerated and substantially increased in number through secondary emission to provide a readily detectable output current.

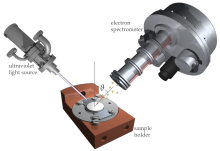

[citation needed] Photoelectron spectroscopy measurements are usually performed in a high-vacuum environment, because the electrons would be scattered by gas molecules if they were present.

Photons hitting a thin film of alkali metal or semiconductor material such as gallium arsenide in an image intensifier tube cause the ejection of photoelectrons due to the photoelectric effect.

[citation needed] The photoelectric effect will cause spacecraft exposed to sunlight to develop a positive charge.

This was first photographed by the Surveyor program probes in the 1960s,[61] and most recently the Chang'e 3 rover observed dust deposition on lunar rocks as high as about 28 cm.

[citation needed] Even if the photoelectric effect is the favoured reaction for a particular interaction of a single photon with a bound electron, the result is also subject to quantum statistics and is not guaranteed.

The photoelectric effect rapidly decreases in significance in the gamma-ray region of the spectrum, with increasing photon energy.

Consequently, high-Z materials make good gamma-ray shields, which is the principal reason why lead (Z = 82) is preferred and most widely used.