British expedition to Tibet

Tibet was ruled by the 13th Dalai Lama under the Ganden Phodrang government as a Himalayan state under the protectorate (or suzerainty) of the Chinese Qing dynasty until the 1911 Revolution, after which a period of de facto Tibetan independence (1912–1951) followed.

[15][16] These events reinforced the Governor-General Lord Curzon's belief that the Dalai Lama intended to place Tibet firmly within a sphere of Russian influence and end its neutrality.

[citation needed] On 19 July 1903, Younghusband arrived at Gangtok, the capital city of the British Indian princely state of Sikkim, where John Claude White was Political Officer, to prepare for his mission.

[21] When Younghusband telegrammed the Viceroy, in an attempt to strengthen the British Cabinet's support of the invasion, that intelligence indicated Russian arms had entered Tibet, Curzon privately silenced him.

"Remember that in the eyes of HMG we are advancing not because of Dorzhiev, or Russian rifles in Lhasa, but because of our Convention shamelessly violated, our frontier trespassed upon, our subjects arrested, our mission flouted, our representations ignored.

They also failed conspicuously to properly defend their natural barriers, frequently offering battle in relatively open ground, where Maxim guns and rifle volleys caused great numbers of casualties.

This force consisted of elements of the 8th Gurkhas, 40th Pathans, 23rd and 32nd Sikh Pioneers, 19th Punjab Infantry and the Royal Fusiliers, as well as mountain artillery, engineers, Maxim machine gun detachments from four regiments and thousands of porters recruited from Nepal and Sikkim.

[citation needed] When no Tibetan or Chinese officials met the British at Khampa Dzong, Younghusband advanced with some 1,150 soldiers, porters, labourers, and thousands of pack animals, to Tuna, 50 miles beyond the border.

[23] The Tibet government, guided by the thirteenth Dalai Lama, alarmed by a foreign power dispatching a military mission to its capital, began marshalling its armed forces.

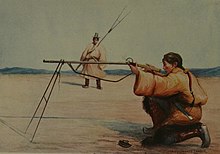

[citation needed] Facing the vanguard of Macdonald's army and blocking the road was a Tibetan force of 3,000 armed with antiquated matchlock muskets, ensconced behind a 5-foot-high (1.5 m) rock wall.

"I got so sick of the slaughter that I ceased fire, though the general’s order was to make as big a bag as possible", wrote Lieutenant Arthur Hadow, commander of the Maxim guns detachment.

"[citation needed] Past the first barrier and with increasing momentum, Macdonald's force crossed abandoned defences at Kangma a week later, and on 9 April attempted to pass through Red Idol Gorge, which had been fortified to prevent passage.

Some hours later, exploratory probes down the pass encountered shooting and a desultory exchange continued till the storm ended around noon, which showed that the Gurkhas had by chance found their way to a position above the Tibetan troops.

Thus faced with shooting from both sides as Sikh soldiers pushed up the hill, the Tibetans moved back, again coming under severe fire from British artillery and retreated in good order, leaving behind 200 dead.

The commission's medical officer, the philanthropic Captain Herbert Walton, attended to the needs of the local populace, notably performing operations to correct cleft palates, a particularly common affliction in Tibet.

[32] Five days after he arrived at Gyantse, and deeming the defences of Changlo Manor secure, Macdonald ordered the main force to begin the march back to New Chumbi to protect the supply line.

Colonel Herbert Brander, Commander of the Mission Escort at Changlo Manor, decided to strike against the Tibetan force assembling at Karo La without consulting Brigadier-General Macdonald, who was two days' riding away.

The garrison responded with its own attacks; some of the Mounted Infantry returned from Karo La, armed with new standard-issue Lee–Enfield rifles, and pursued Tibetan horsemen, and one of the Maxims was stationed on the roof and short bursts of machine-gun fire met targets as they appeared on the walls of the Dzong.

On 24 May a company of the 32nd Sikh pioneers arrived and Captain Seymour Shepard, DSO, 'a legend in the Indian Army' reached Gyantse, commanding a group of sappers, which lifted British morale.

Reluctantly Younghusband did deliver an ultimatum in two letters, one addressed to the Dalai Lama and one to the Chinese amban, Manchu Resident in Lhasa, Yu-t'ai, though, as he wrote to his sister, he was against this course of action for he saw it as "giving them another chance of negotiating".

[41][verification needed] On 28 June a final obstacle to assaulting Gyantse Dzong was overcome when the Tsechen monastery, to the north-west, and the fortress that guarded its rear were cleared by two companies of Gurkhas, the 40th Pathans and two waves of infantry.

This attitude was born of a mix of justifiable fear of the Maxim Guns, and faith in the solid rock of their defences, yet in every battle they were disappointed, primarily by their poor weaponry and inexperienced officers.

The more patient General Macdonald, meanwhile, was subject to a campaign that sought to undermine his authority; Captain O'Connor wrote to Helen Younghusband on 3 July that "He should be removed & another & better man-a fighting general- substituted".

At the Karo La, the Wide-Mouthed Pass that had been the scene of fighting two and a half months earlier, the Gurkhas skirmished with a determined group of Tibetan fighters on the heights to the left and right.

By 22 July, the troops camped under the wall of another fortress, Peté Dzong, deserted and in ruins, while Mounted Infantry pushed on ahead to seize the crossing at Chushul Chakzam, the Iron Bridge.

The Tibetan Council of Ministers and the General Assembly began to submit to pressure on the terms as August progressed, except on the matter of the indemnity which they believed impossibly high for a poor country.

[46][verification needed] Eventually however Younghusband intimidated the regent, Ganden Tri Rinpoche, and the Tsongdu (Tibetan National Assembly), into signing a treaty on 7 September 1904, drafted by himself, known subsequently as the Convention of Lhasa.

The Secretary of State for India, St John Brodrick, had in fact expressed the need for it to be "within the power of the Tibetans to pay" and given Younghusband a free hand to be "guided by circumstances in this matter".

The Tibetans had lost the war but had seen China humbled by its failure to defend its client state from foreign incursion, and had pacified the British by signing an unenforceable and largely irrelevant treaty.

[62] The Chinese government has turned Gyantze Dzong into a "Resistance Against the British Museum", promoting these views, as well as other themes such as the brutal living conditions endured by Tibetan serfs who supposedly loved their motherland (China).