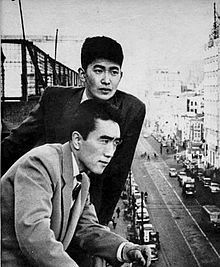

Yukio Mishima

Mishima's work is characterized by "its luxurious vocabulary and decadent metaphors, its fusion of traditional Japanese and modern Western literary styles, and its obsessive assertions of the unity of beauty, eroticism and death",[11] according to author Andrew Rankin.

[37] Natsuko had been raised in the household of Prince Arisugawa Taruhito, and she maintained considerable aristocratic pretensions even after marrying Sadatarō, a bureaucrat who had made his fortune in the newly opened colonial frontier in the north, and who eventually became Governor-General of Karafuto Prefecture on Sakhalin Island.

[50][51] Mishima was enrolled at the age of six in the elite Gakushūin, the Peers' School in Tokyo, which had been established in the Meiji period to educate the Imperial family and the descendants of the old feudal nobility.

[e] He also sent a copy of the manuscript to his teacher Fumio Shimizu (清水文雄), who was so impressed that he and his fellow editorial board members decided to publish it in their literary magazine Bungei Bunka (文藝文化).

[57][58] In the editorial notes of Bungei Bunka magazine in 1941, when this debut work was serialized, Hasuda praised Mishima's genius: "This youthful author is a heaven-sent child of eternal Japanese history.

"[59] Hasuda, who became something of a mentor to Mishima, was an ardent nationalist and a fan of Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801), a scholar of kokugaku from the Edo period who preached Japanese traditional values and devotion to the Emperor.

Another story from 1954, The Boy Who Wrote Poetry (詩を書く少年, Shi o kaku shōnen), was similarly based on Mishima's memories of his time at Gakushūin Junior High School.

I realized vividly that my future life would never attain heights of glory sufficient to justify my having escaped death in the army...[75][76]The veracity of this account is impossible to know for certain, but what is unquestionable is that Mishima did not speak out against the doctor's diagnosis of tuberculosis.

[106] These newly converted leftists held great influence in the Japanese literary world immediately following the end of the war, which Mishima found difficult to accept, and he denounced them as "opportunists" in letters to friends.

Uncertain of who else to turn to, Mishima took the manuscripts for The Middle Ages (中世, Chūsei) and The Cigarette (煙草, Tabako) with him, visited Kawabata in Kamakura, and asked for his advice and assistance in January 1946.

Thereafter, Kikuwaka devotes himself to spiritualism in an attempt to heal Yoshimasa's sadness by allowing Yoshihisa's ghost to possess his body, and eventually dies in a double-suicide with a miko (shrine maiden) who falls in love with him.

The Sound of Waves, set on the small island of "Kami-shima" where a traditional Japanese lifestyle continued to be practiced, depicts a pure, simple love between a fisherman and a female pearl and abalone diver.

Alongside Kōbō Abe's Woman of the Dunes, published that same year, Okuno considered A Beautiful Star an "epoch-making work" which broke free of literary taboos and preexisting notions of what literature should be in order to explore the author's personal creativity.

[143] Shibusawa's sexually explicit translation became the focus of a sensational obscenity trial remembered in Japan as the "Juliette Case" (サド裁判, Sado saiban), which was ongoing as Mishima wrote the play.

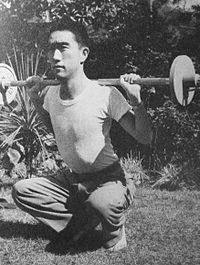

American author Donald Richie gave an eyewitness account of seeing Mishima, dressed in a loincloth and armed with a sword, posing in the snow for one of Tamotsu Yatō's photoshoots.

[157] In 1954, he fell in love with Sadako Toyoda (豊田貞子), who became the model for main characters in The Sunken Waterfall (沈める滝, Shizumeru taki) and The Seven Bridges (橋づくし, Hashi zukushi).

However, the ruling for the plaintiffs declared, "In addition to clerical content, these letters describe the Mishima's own feelings, his aspirations, and his views on life, in different words from those in his literary works.

In 1960, the author Shichirō Fukazawa had published the satirical short story The Tale of an Elegant Dream (風流夢譚, Fūryū Mutan) in the mainstream magazine Chūō Kōron.

It contained a dream sequence (in which the Emperor and Empress are beheaded by a guillotine) that led to outrage from right-wing ultra-nationalist groups, and numerous death threats against Fukazawa, any writers believed to have been associated with him, and Chūō Kōron magazine itself.

[172] On 1 February 1961, Kazutaka Komori, a seventeen-year-old rightist, broke into the home of Hōji Shimanaka, the president of Chūō Kōron, killed his maid with a knife and severely wounded his wife.

He wrote a play titled The Harp of Joy (喜びの琴, Yorokobi no koto), but star actress Haruko Sugimura and other Communist Party-affiliated actors refused to perform because the protagonist held anti-communist views and mentioned criticism about a conspiracy of world communism in his lines.

Mishima expressed his excitement in his report on the opening ceremonies: "It can be said that ever since Lafcadio Hearn called the Japanese "the Greeks of the Orient", the Olympics were destined to be hosted by Japan someday.

[196] In February 1967, Mishima joined fellow authors Yasunari Kawabata, Kōbō Abe, and Jun Ishikawa in issuing a statement condemning China's Cultural Revolution for suppressing academic and artistic freedom.

[200] On his way home from India, Mishima also stopped in Thailand and Laos; his experiences in the three nations became the basis for portions of his novel The Temple of Dawn, the third in his tetralogy The Sea of Fertility.

[209] Mishima wrote of My Friend Hitler, "You may read this tragedy as an allegory of the relationship between Ōkubo Toshimichi and Saigō Takamori" (two heroes of Japan's Meiji Restoration who initially worked together but later had a falling out).

[213] In a review of the English translation, novelist Ian Thomson called it a "pulp noir" and a "sexy, camp delight", but also noted that, "beneath the hard-boiled dialogue and the gangster high jinks is a familiar indictment of consumerist Japan and a romantic yearning for the past.

[215] On 25 February 1968, he and several other right-wingers met at the editorial offices of the recently founded minzoku-ha monthly magazine Controversy Journal (論争ジャーナル, Ronsō jaanaru), where they pricked their little fingers and signed a blood oath promising to die if necessary to prevent a left-wing revolution from occurring in Japan.

In a final "written appeal" (檄, Geki) that Morita and Ogawa scattered copies of from the balcony, Mishima expressed his dissatisfaction with the half-baked nature of the JSDF: "It is self-evident that the United States would not be pleased with a true Japanese volunteer army protecting the land of Japan.

[263] One researcher has speculated that Mishima chose November 25 for his coup attempt in order to set his period of bardo until his reincarnation, such that 49th day after his death would coincide with his birthday, 14 January.

For example, stones have been erected at Hachiman Shrine in Kakogawa City, Hyogo Prefecture, where his grandfather's permanent domicile was;[272] in front of the 2nd company corps at JGSDF Camp Takigahara;[273] and in one of Mishima's acquaintance's home garden.