Koreans in Japan

They are a group distinct from South Korean nationals who have immigrated to Japan since the end of World War II and the division of Korea.

However, in 1988, a Mindan youth group called Zainihon Daikan Minkoku Seinendan (Korean: 재일본대한민국청년회, Japanese: 在日本大韓民国青年会) published a report titled, "Father, tell us about that day.

While some families today can ultimately trace their ancestry to the immigrants, they were generally absorbed into Japanese society and are not considered a distinct modern group.

][citation needed] According to the Nihon Kōki historical text, in 814, six people, including a Silla man called Karanunofurui (Korean: 가라포고이, Japanese: 加羅布古伊; presumed to be of gaya descent) became naturalized in Japan's Minokuni (美濃國) region.

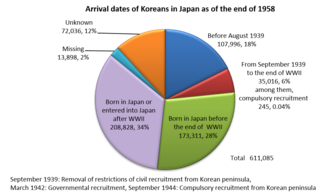

[16][verification needed] In 1939, the Japanese government introduced the National Mobilization Law and conscripted Koreans to deal with labor shortages due to World War II.

[26] In Official Correspondence of 1949, Shigeru Yoshida, the prime minister of Japan, proposed the deportation of all Zainichi Koreans to Douglas MacArthur, the American Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, and said the Japanese government would pay all of the cost.

Yoshida stated that it was unfair for Japan to purchase food for illegal Zainichi Koreans, claiming that they did not contribute to the Japanese economy and that they supposedly committed political crimes by cooperating with communists.

[31] When Expo 2005 was held, the Japanese government had a visa waiver program with South Korea for a limited period under the condition that the visitor's purpose was sightseeing or business, and later extended it permanently.

This cultural phenomenon, encompassing Korean music, television dramas, films, and cuisine, has gained widespread attention not only in Japan but also globally.

Despite historical tensions between the two countries, Japan remains an attractive destination for many South Koreans seeking employment and business prospects.

The close geographical proximity and strong economic ties between Japan and South Korea have facilitated increased migration and investment between the two nations.

Many Korean nationals have sought employment opportunities in sectors such as manufacturing, technology, healthcare, and hospitality, contributing to Japan's workforce and economy.

A North Korean-sponsored repatriation programme with support of the Chōsen Sōren (The General Association of Korean Residents in Japan) officially began in 1959.

Around one hundred such repatriates are believed to have later escaped from North Korea; the most famous is Kang Chol-Hwan[disputed – discuss], who published a book about his experience, The Aquariums of Pyongyang.

One returnee who later defected back to Japan, known only by his Japanese pseudonym Kenki Aoyama, worked for North Korean intelligence as a spy in Beijing.

Mindan has also traditionally operated a school system for the children of its members, although it has always been less widespread and organized compared to its Chongryon counterpart, and is said to be nearly defunct at the present time.

Its policies have included: For a long time, Chongryon enjoyed unofficial immunity from searches and investigations, partly because authorities were reluctant to carry out any actions which could provoke not only accusations of xenophobia but lead to an international incident.

[citation needed] In March 2006, police raided six Chongryon-related facilities in an investigation into the circumstances surrounding the June 1980 disappearance of one of the alleged abductees, Tadaaki Hara.

Outraged senior Mindan officials joined mainstream Japanese politicians and media in sharply criticizing Chongryon's silence over the matter.

Zainichi Koreans were often forced into low-wage labor, lived in segregated communities, and faced barriers to their cultural and social practices.

Even of those who were able to secure jobs, many ended up working in coal mines, construction sites, and factories under harsh conditions that were markedly worse than those endured by their Japanese counterparts.

The disparity was not limited to wages alone; Koreans also faced longer working hours and were subjected to physical abuse by supervisors who enforced strict discipline to maximize productivity.

They were segregated into specific neighborhoods, commonly referred to as "Korean Towns," (which still exist today in Shin-Ōkubo and Ikuno-ku) where living conditions were poor, sanitation was inadequate, and access to public services like healthcare and education was severely limited.

Korean children faced bullying and discrimination in schools, which often led to high dropout rates and limited their educational and, subsequently, economic opportunities.

Changes in legal and social recognition began to emerge towards the late 20th century, influenced by both domestic advocacy by human rights groups and international pressure.

In order to be naturalized as Japanese citizens, Zainichi Koreans previously had to go through multiple, complex steps, requiring collection of information about their family and ancestors stretching back ten generations.

The right to claim social welfare benefits was granted in 1954, followed by access to the national health insurance structures (1960s) and state pensions (1980s).

There is some doubt over the legality of some of these policies, as the Public Assistance Law, which governs social welfare payments, is seen to apply only to "Japanese nationals".

[69] There are a few Kankoku Gakkō (Korean: 한국학교; 韓國學校, Japanese: 韓国学校) located in Tokyo, Osaka, Ibaraki, Kyoto, and Ishioka, which receive sponsorship from South Korea and are operated by Mindan.

Well-known ethnic Koreans who use Japanese names include Hanshin Tigers star Tomoaki Kanemoto, pro wrestlers Riki Choshu and Akira Maeda, and controversial judoka and mixed martial artist Yoshihiro Akiyama.