Zanabazar

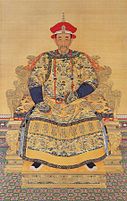

[3] Over the course of nearly 60 years, Zanabazar advanced the Gelugpa school of Buddhism among the Mongols, supplanting or synthesizing Sakya or "Red Hat" Buddhist traditions that had prevailed in the area, while strongly influencing social and political developments in 17th century Mongolia.

In addition to his spiritual and political roles, Zanabazar was a polymath – a prodigious sculptor, painter, architect, poet, costume designer, scholar and linguist, who is credited with launching Mongolia's seventeenth century cultural renaissance.

In 1578 Abtai's uncle, Altan Khan, bestowed the Mongolian language title "Dalai Lama" on the Gelug leader Sonam Gyatso.

[8] In 1639, an assembly of Khalkha nobles at Shireet Tsagaan nuur (75 km east of the former capital Karakorum) recognized Zanabazar as an Öndör Gegeen (high saint) and the Khalkh's supreme religious leader, even though he was only four years old at the time.

[12] The Dalai Lama identified him as the reincarnation of the scholar Taranatha (1575–1634), who had led the rival Jonang school of Tibetan Buddhism until his death in Mongolia one year before Zanabazar's birth.

The Tibetan Buddhist hierarchy also granted him the additional title Bogd Gegeen, or "Highest Enlightened Saint", designating him the top-ranking Lama in Mongolia.

[14] Following his journeys to Tibet in 1651 and again in 1656, Zanabazar and his retinue of Tibetan lamas founded a series of Gelug-influenced monasteries, temples, and Buddhist shrines throughout Mongol territory, the most noteworthy being a stupa to house Taranatha's remains, the Saridgiin Monastery in the Khentii mountains (completed in 1680), and several movable temples which contained paintings, sculptures, wall hangings and ritual objects influenced by the Tibetan-Nepalese style and either imported from Tibet or produced by Zanabazar or his students.

As Galdan's forces swept eastward into Khalka territory in 1688, Zanabazar and nearly 20,000 Khalkha refugees fled south into present day Inner Mongolia to seek the protection of the Qing Emperor.

[18] Motivated by the appeals of Zanabazar, whom he greatly admired,[19] as well as the threat posed by a strong, unified Mongol state under Dzungar rule, the Kangxi Emperor dispatched Qing armies north to subdue the Galdan's forces.

[28] As his political influence grew, his artwork became a form of diplomacy,[27] used in negotiations with the Dzungar leader Galdan Boshugtu Khan and to gain the favor of the Kangxi Emperor, paving the way for incorporation of outer Mongolia into Qing protectorate.

[4] His sculptures, portraying peaceful and contemplative female figures, are beautifully proportioned with facial features characterized by high foreheads, thin, arching eyebrows, high- bridged noses, and small, fleshy lips.

[34] His artistic works are generally regarded as the apogee of Mongolian aesthetic development and spawned a cultural renaissance among Mongols in the late 17th century.

Even during the country's socialist era (1921-1991) he was acknowledged to be as a prominent scholar (his religious roles quietly discarded) and recognized for his artistic and cultural achievements.

[35] As a political personality, however, socialist authorities portrayed Zanabazar as a traitor and deceiver of the masses,[36] responsible for the loss of Mongolian sovereignty to the Manchu.

[35] In the post socialist era, however, there has been a reevaluation of his image to where his actions in negotiating the Khalkha's submission to the Qing are considered to have been in the long term interests of Mongolia,[35] and he is generally exonerated for his role in 1691.