Zazen

For example, the famous translator Kumārajīva (344–413) translated a work termed Zuòchán sān mēi jīng (A Manual on the Samādhi of Sitting Meditation) and the Chinese Tiantai master Zhiyi (538–597 CE) wrote some very influential works on sitting meditation.

The practice can be done with various methods, such as following the breath (anapanasati), mentally repeating a phrase (which could be a koan, a mantra, a huatou or nianfo) and a kind of open monitoring in which one is aware of whatever comes to our attention (sometimes called shikantaza or silent illumination).

Repeating a huatou, a short meditation phrase, is a common method in Chinese Chan and Korean Seon.

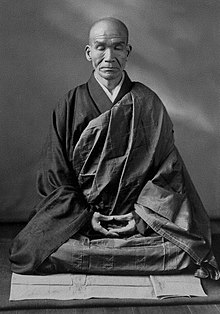

In lecture four, Yasutani lists five kinds of zazen: In Zen temples and monasteries, practitioners traditionally sit zazen together in a meditation hall usually referred to as a zendo, each sitting on a cushion called a zafu[2] which itself may be placed on a low, flat mat called a zabuton.

Practice is typically to be continued in one of these ways until there is adequate "one-pointedness" of mind to constitute an initial experience of samadhi.

[1][16] The aim of zazen is just sitting, that is, suspending all judgemental thinking and letting words, ideas, images and thoughts pass by without getting involved in them.

[6][17] Practitioners do not use any specific object of meditation,[6] instead remaining as much as possible in the present moment, aware of and observing what is occurring around them and what is passing through their minds.