Zeckendorf's theorem

In mathematics, Zeckendorf's theorem, named after Belgian amateur mathematician Edouard Zeckendorf, is a theorem about the representation of integers as sums of Fibonacci numbers.

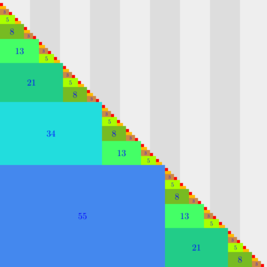

Zeckendorf's theorem states that every positive integer can be represented uniquely as the sum of one or more distinct Fibonacci numbers in such a way that the sum does not include any two consecutive Fibonacci numbers.

More precisely, if N is any positive integer, there exist positive integers ci ≥ 2, with ci + 1 > ci + 1, such that where Fn is the nth Fibonacci number.

Such a sum is called the Zeckendorf representation of N. The Fibonacci coding of N can be derived from its Zeckendorf representation.

For example, the Zeckendorf representation of 64 is There are other ways of representing 64 as the sum of Fibonacci numbers but these are not Zeckendorf representations because 34 and 21 are consecutive Fibonacci numbers, as are 5 and 3.

For any given positive integer, its Zeckendorf representation can be found by using a greedy algorithm, choosing the largest possible Fibonacci number at each stage.

While the theorem is named after the eponymous author who published his paper in 1972, the same result had been published 20 years earlier by Gerrit Lekkerkerker.

[1] As such, the theorem is an example of Stigler's Law of Eponymy.

Zeckendorf's theorem has two parts: The first part of Zeckendorf's theorem (existence) can be proven by induction.

Now suppose each positive integer a < n has a Zeckendorf representation (induction hypothesis) and consider b = n − Fj .

Since b < n, b has a Zeckendorf representation by the induction hypothesis.

As a result, n can be represented as the sum of Fj and the Zeckendorf representation of b, such that the Fibonacci numbers involved in the sum are distinct.

[2] The second part of Zeckendorf's theorem (uniqueness) requires the following lemma: The lemma can be proven by induction on j.

of distinct non-consecutive Fibonacci numbers which have the same sum,

from which the common elements have been removed (i. e.

had equal sum, and we have removed exactly the elements from

are both non-empty and let the largest member of

contain no common elements, Fs ≠ Ft.

Without loss of generality, suppose Fs < Ft. Then by the lemma,

Now assume (again without loss of generality) that

, proving that each Zeckendorf representation is unique.

on natural numbers a, b: given the Zeckendorf representations

) A simple rearrangement of sums shows that this is a commutative operation; however, Donald Knuth proved the surprising fact that this operation is also associative.

[3] The Fibonacci sequence can be extended to negative index n using the rearranged recurrence relation which yields the sequence of "negafibonacci" numbers satisfying Any integer can be uniquely represented[4] as a sum of negafibonacci numbers in which no two consecutive negafibonacci numbers are used.

For example: 0 = F−1 + F−2 , for example, so the uniqueness of the representation does depend on the condition that no two consecutive negafibonacci numbers are used.

This gives a system of coding integers, similar to the representation of Zeckendorf's theorem.

In the string representing the integer x, the nth digit is 1 if F−n appears in the sum that represents x; that digit is 0 otherwise.

For example, 24 may be represented by the string 100101001, which has the digit 1 in places 9, 6, 4, and 1, because 24 = F−1 + F−4 + F−6 + F−9 .

The integer x is represented by a string of odd length if and only if x > 0.

This article incorporates material from proof that the Zeckendorf representation of a positive integer is unique on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.