Greedy algorithm

For example, a greedy strategy for the travelling salesman problem (which is of high computational complexity) is the following heuristic: "At each step of the journey, visit the nearest unvisited city."

This heuristic does not intend to find the best solution, but it terminates in a reasonable number of steps; finding an optimal solution to such a complex problem typically requires unreasonably many steps.

Greedy algorithms produce good solutions on some mathematical problems, but not on others.

Most problems for which they work will have two properties: A common technique for proving the correctness of greedy algorithms uses an inductive exchange argument.

One example is the travelling salesman problem mentioned above: for each number of cities, there is an assignment of distances between the cities for which the nearest-neighbour heuristic produces the unique worst possible tour.

There are a few variations to the greedy algorithm:[5] Greedy algorithms have a long history of study in combinatorial optimization and theoretical computer science.

Greedy heuristics are known to produce suboptimal results on many problems,[6] and so natural questions are: A large body of literature exists answering these questions for general classes of problems, such as matroids, as well as for specific problems, such as set cover.

A matroid is a mathematical structure that generalizes the notion of linear independence from vector spaces to arbitrary sets.

Similar guarantees are provable when additional constraints, such as cardinality constraints,[9] are imposed on the output, though often slight variations on the greedy algorithm are required.

Other problems for which the greedy algorithm gives a strong guarantee, but not an optimal solution, include Many of these problems have matching lower bounds; i.e., the greedy algorithm does not perform better than the guarantee in the worst case.

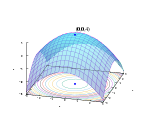

Greedy algorithms typically (but not always) fail to find the globally optimal solution because they usually do not operate exhaustively on all the data.

They can make commitments to certain choices too early, preventing them from finding the best overall solution later.

If a greedy algorithm can be proven to yield the global optimum for a given problem class, it typically becomes the method of choice because it is faster than other optimization methods like dynamic programming.

Using greedy routing, a message is forwarded to the neighbouring node which is "closest" to the destination.

Location may also be an entirely artificial construct as in small world routing and distributed hash table.