Zeno's paradoxes

[2] Zeno devised these paradoxes to support his teacher Parmenides's philosophy of monism, which posits that despite our sensory experiences, reality is singular and unchanging.

The paradoxes famously challenge the notions of plurality (the existence of many things), motion, space, and time by suggesting they lead to logical contradictions.

Zeno's work, primarily known from second-hand accounts since his original texts are lost, comprises forty "paradoxes of plurality," which argue against the coherence of believing in multiple existences, and several arguments against motion and change.

[2] Of these, only a few are definitively known today, including the renowned "Achilles Paradox", which illustrates the problematic concept of infinite divisibility in space and time.

[1][2] These paradoxes have stirred extensive philosophical and mathematical discussion throughout history,[1][2] particularly regarding the nature of infinity and the continuity of space and time.

[1] However, modern solutions leveraging the mathematical framework of calculus have provided a different perspective, highlighting Zeno's significant early insight into the complexities of infinity and continuous motion.

[1] Zeno's paradoxes remain a pivotal reference point in the philosophical and mathematical exploration of reality, motion, and the infinite, influencing both ancient thought and modern scientific understanding.

[1][2] Diogenes Laërtius, citing Favorinus, says that Zeno's teacher Parmenides was the first to introduce the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise.

[6] Some of Zeno's nine surviving paradoxes (preserved in Aristotle's Physics[7][8] and Simplicius's commentary thereon) are essentially equivalent to one another.

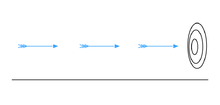

The resulting sequence can be represented as: This description requires one to complete an infinite number of tasks, which Zeno maintains is an impossibility.

[17]In the arrow paradox, Zeno states that for motion to occur, an object must change the position which it occupies.

With the epsilon-delta definition of limit, Weierstrass and Cauchy developed a rigorous formulation of the logic and calculus involved.

[35][36] Some philosophers, however, say that Zeno's paradoxes and their variations (see Thomson's lamp) remain relevant metaphysical problems.

It may be that Zeno's arguments on motion, because of their simplicity and universality, will always serve as a kind of 'Rorschach image' onto which people can project their most fundamental phenomenological concerns (if they have any).

"[10] An alternative conclusion, proposed by Henri Bergson in his 1896 book Matter and Memory, is that, while the path is divisible, the motion is not.

[37][38] In 2003, Peter Lynds argued that all of Zeno's motion paradoxes are resolved by the conclusion that instants in time and instantaneous magnitudes do not physically exist.

[19] Based on the work of Georg Cantor,[42] Bertrand Russell offered a solution to the paradoxes, what is known as the "at-at theory of motion".

Jean Paul Van Bendegem has argued that the Tile Argument can be resolved, and that discretization can therefore remove the paradox.

The second of the Ten Theses of Hui Shi suggests knowledge of infinitesimals:That which has no thickness cannot be piled up; yet it is a thousand li in dimension.

Among the many puzzles of his recorded in the Zhuangzi is one very similar to Zeno's Dichotomy: "If from a stick a foot long you every day take the half of it, in a myriad ages it will not be exhausted."

Due to the lack of surviving works from the School of Names, most of the other paradoxes listed are difficult to interpret.

[56] "What the Tortoise Said to Achilles",[57] written in 1895 by Lewis Carroll, describes a paradoxical infinite regress argument in the realm of pure logic.