Xuande Emperor

In the early Xuande Emperor's reign, a prolonged war in Jiaozhi (present-day northern Vietnam) ended with Ming defeat and the Viet's independence.

The emperor sought order through purges in the Censorate and military service reforms in 1428, but these didn't fully address inefficiencies and low morale among hereditary soldiers.

He chose to cancel the move of the capital to Nanjing due to his familiarity with Beijing, where he grew up, and his shared concern with the Yongle Emperor for the security of the northern border.

[12] Underestimating his young nephew as a formidable opponent, he also failed to recognize the strength of the government, which had functioned effectively during the Yongle Emperor's extended absences on campaigns in Mongolia.

[1] The emperor initially hesitated, but eventually succumbed to pressure from Grand Secretary Yang Rong and other advisors, ultimately taking personal command of the punitive expedition on 9 September.

An investigation revealed that other relatives of the emperor, including the rebel's brother Zhu Gaosui, were also involved in the rebellion, but they were not punished in order to preserve the prestige of the imperial family.

Within a few months, Gu Zuo dismissed 43 censors from the Beijing and Nanjing offices, and Liu Quan himself was punished for numerous abuses of power.

[20] The system of grand coordinators reached its final form during the Zhengtong era (1436–1449),[21] when they were assigned to all provinces except Fujian and six of the nine frontier garrisons on the northern border.

[22] Additionally, capable officers had limited opportunities for advancement during times of peace, resulting in the army being led by individuals who inherited their positions without merit.

[21] In an attempt to address these issues, inspection officials were appointed in 1427 to verify the condition and numbers of the army detachments and restore discipline, but their efforts were largely ineffective.

The imposition of high taxes and levies placed an unbearable burden on the economy of wealthy regions in China, resulting in a decline in government revenue.

In 1433, Governor of South Zhili Zhou Chen began to collect land taxes in silver in the most heavily burdened prefectures of Jiangnan.

[37] During the early years of the Xuande Emperor's reign, a major issue that arose was the war in Jiaozhi Province, or Đại Việt under Ming rule (present-day northern Vietnam), which had been ongoing since 1408.

In response, the emperor appointed a new commander, Wang Tong (王通), and a new head of civil administration, minister Chen Qia (陳洽),[38] in May 1426.

Meanwhile, Lê Lợi continued to expand his operations into the Red River Valley, posing a threat to Đông Quan, the capital of the province (present-day Hanoi).

In the aftermath of this disaster, Wang Tong, without the emperor's knowledge, accepted Lê Lợi's proposal and began withdrawing troops from Jiaozhi on 12 November.

[43] Zheng He brought envoys from Sri Lanka, Cochin, Calicut, Hormuz, Aden, the East African coast, and other countries to China, which pleased the emperor.

With the opening of the Grand Canal, the need to transport rice by sea to the north disappeared, leading officials to view naval expeditions as expensive and unnecessary imperial ventures.

[44] This decision had long-term negative consequences, as it weakened the morale and strength of the Ming fleet, leaving them later unable to effectively deal with the wokou pirates.

[46] The Xuande Emperor made repeated attempts to establish relations with Japan, but shogun Yoshimochi (shōgun 1394–1425, effectively ruled 1408–1428) adamantly refused any communication.

[14] After 1433, Japanese delegations arriving in China were primarily composed of agents of daimyos, monasteries, and temples who were eager to access the Chinese market.

[51] According to Chinese records, the emperor often requested horses from the Koreans, while also asking them not to send gold, silver, or other unusual gifts that were not produced in their country.

Additionally, the emperor rejected a request to admit Korean students to the Imperial University in Beijing, instead donating a collection of Confucian classics and historical literature to Korea as a replacement.

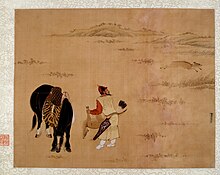

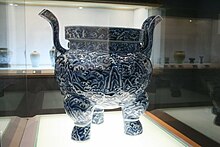

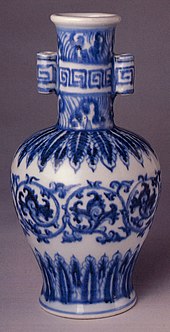

In 2007, Robert D. Mowry, the curator of Chinese Art Collections at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, described him as "the only Ming emperor who displayed genuine artistic talent and interest".

[10] In the autumn and winter of 1434, the emperor led a military detachment on a tour of the northern border, but upon returning to Beijing, he fell ill.[59] He was sick for almost two months,[9] until he suddenly died on 31 January 1435.

Some civil officials criticized his indulgence in frequently sending eunuchs to the southern provinces seeking entertainers and virgins for his harem, and his entrusting greater authority to eunuchs— which caused problems for his successors.

[9] He saw himself as a warrior and, like the Yongle Emperor, personally led military campaigns, but his actions were relatively small (such as suppressing his uncle's rebellion) or insignificant (such as clashes with the Mongols on the northern border).

[59] As a result, subsequent generations of officials viewed the Xuande era as a golden age of ideal governance, in contrast to the factional conflicts and institutional decay of their own time.

The failure of the war in Jiaozhi and the subsequent defeat in Tumu were constant arguments used by officials against military adventures,[19] which could potentially return power to the hands of the generals and disrupt the establishment of the Ming dynasty's dominance in government.

The Ming dynasty's originally diverse elites, including generals, members of the imperial family, Confucian officials, and eunuchs, saw the first two groups lose their influence on the governance of the country.