Zia ol Din Tabatabaee

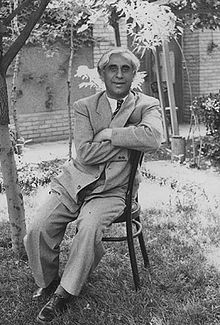

Seyyed Zia al-Din Tabataba'i Yazdi (Persian: سید ضیاءالدین طباطبایی یزدی; June 1889 – 29 August 1969) was an Iranian journalist and pro-Constitution politician who, with the help of Reza Shah, spearheaded the 1921 Persian coup d'état and aimed to reform Qajar rule, which was in domestic turmoil and under foreign intervention.

When Zia was twelve he went to Tehran, and at fifteen, he moved back to Shiraz in the company of his grandmother, who was said to be a woman of unusual erudition and independence.

After Ra'ad was shut down by the authorities, he started two other newspapers called Shargh (East), followed by Bargh (Lightning), and became active in the Persian Constitutional Revolution.

Zia's newspapers usually consisted of blistering attacks on prominent politicians of the Qajar monarchy, which caused them to be closed several times.

Zia decided to resume his journalism, this time focusing on his famous newspaper Ra'ad (Thunder), and came out in strong support of the British in the war.

[4] Zia came to power in a coup d'état on February 22, 1921 (3 Esfand 1299) with the help of Reza Khan Mirpanj, who later became the Shah of Persia.

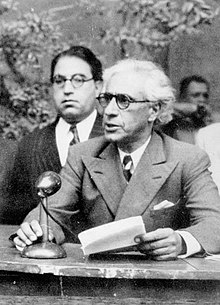

Zia gave a fierce speech in parliament against the corrupt political class that tenaciously defended its privileges from the pre-parliamentary period which had brought Persia to the brink of ruin.

Within hours of taking power, the new government immediately declared a new order, which included, "all the residents of the city of Tehran must keep quiet.

"[5] Zia and Reza Khan, arrested some four hundred rich people and aristocrats who had inherited wealth and power over the span of ten to twenty years while the country experienced poverty, corruption, famine, instability and chaos.

[6] According to Zia, these "few hundred nobles, who hold the reins of power by inheritance, sucked, leech-like, the blood of the people".

[7] Zia declared that his cabinet's program included far-reaching measures such as the "formation of an army...eventual abolition of the capitulations...establishment of friendly ties with the Soviet Union."

At the same time, he tried to implement a truly impressive number of changes in the capital itself—from ordering new rules of hygiene for stores that handled foodstuffs to bringing street lights to the city's notoriously dark roads.

[8] His political reform program envisaged that the entire legal system of Iran should be modernized and aligned with European standards.

Moreover, some of his decisions such as ordering a ban on alcohol, bars, and casinos, as well as, closing shops on Fridays and on religious holidays, angered merchants.

It was also not long before the families of those arrested organized a political campaign against Zia, calling his administration "the black cabinet", which resulted in constant unrest.

A few years later Mirzadeh Eshghi in his ode of the fourth parliament wrote: "It is not enough as much we admire Zia, we won't afford it....I say something but he was something else....".

For a while he sold Persian carpets in Berlin; then he moved to Geneva, where he tried, unsuccessfully, to write a book with the help of his friend Mohammad-Ali Jamalzadeh, the famous exiled Iranian writer.

During the last fifteen years of his life, Zia became an advisor and conduit to the shah, who was hesitant at first, but preferred him over Ahmad Qavam, with whom he had a fall out with.

Zia also claimed to have told the shah that "a king can't fly around his capital in a helicopter, but must mingle with the masses".

[7] The famous "Leading Personalities" files of the British Foreign Office described Zia as: "a man of outstanding singles of purpose and courage.

Personally attractive, religious without being fanatical or obscurantist...appointed prime minister with full powers by Ahmad Shah on the 1st of March 1921 and affected numerous arrests.

His reforms were too radical for the country and the time, and he fell from power in June....It is no exaggeration to say that [in the postwar years, he] rallied the Anti-Tudeh forces in Persian and thus made it possible to resist intensive Soviet Pressure when it came.