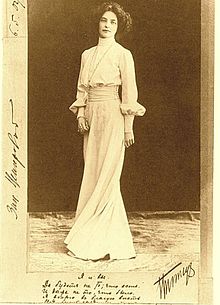

Zinaida Gippius

After living in Poland they moved to France, and then to Italy, continuing to publish and to take part in Russian émigré circles, though Gippius's harsh literary criticism made enemies.

The tragedy of the exiled Russian writer was a major topic for Gippius in emigration, but she also continued to explore mystical and covertly sexual themes, publishing short stories, plays, novels, poetry, and memoirs.

Taking lessons from governesses and visiting tutors, they attended schools sporadically in whatever city the family happened to stay for a significant period of time (Saratov, Tula and Kiev, among others).

[5][6] At the age of 48 Nikolai Gippius died of tuberculosis,[7][8] and Anastasia Vasilyevna, knowing that all of her girls had inherited a predisposition to the illness that killed him, moved the family southwards, first to Yalta (where Zinaida had medical treatment) then in 1885 to Tiflis, closer to their uncle Alexander Stepanov's home.

[10] It was only in Borzhomi where her uncle Alexander, a man of considerable means, rented a dacha for her, that she started to get back to normal after the profound shock caused by her beloved father's death.

[11] A good-looking girl, Zinaida attracted a lot of attention in Borzhomi, but Merezhkovsky, a well-educated introvert, impressed her first and foremost as a perfect kindred spirit.

They had a short honeymoon tour involving a stay in the Crimea, then returned to Saint Petersburg and moved into a flat in the Muruzi House, which Merezhkovsky's mother had rented and furnished for them as a wedding gift.

Enjoying the notoriety, she exploited her androgynous image, used male clothes and pseudonyms, shocked her guests with insults ('to watch their reaction', as she once explained to Nadezhda Teffi), and for a decade remained the Russian symbol of 'sexual liberation', holding high what she in one of her diary entries termed as the 'cross of sensuality'.

[4] Analyzing the roots of the crisis that Russian culture had fallen into, Gippius (somewhat paradoxically, given her 'demonic' reputation) suggested as a remedy the 'Christianization' of it, which in practice meant bringing the intelligentsia and the Church closer together.

Merging faith and intellect, according to Gippius, was crucial for the survival of Russia; only religious ideas, she thought, would bring its people enlightenment and liberation, both sexual and spiritual.

This 'gathering for free discussion', focusing on the synthesis of culture and religion, brought together an eclectic mix of intellectuals and was regarded in retrospect as an important, if short-lived attempt to pull Russia back from the major social upheavals it was headed for.

By the time Novy Put folded (due to a conflict caused by the newcomer Sergei Bulgakov's refusal to publish her essay on Alexander Blok), Gippius (as Anton Krainy) had become a prominent literary critic, contributing mostly to Vesy (Scales).

In 1906 Gippius published the collection of short stories Scarlet Sword (Алый меч), and in 1908 the play Poppie Blossom (Маков цвет) came out, with Merezhkovsky and Filosofov credited as co-authors.

The heated discussion over the Vekhi manifesto led to a clash between the Merezhkovskys and Filosofov on the one hand and Vasily Rozanov on the other; the latter quit and severed ties with his old friends.

Still, Gippius launched a support-the-soldiers campaign of her own, producing a series of frontline-forwarded letters, each combining stylized folk poetic messages with small tobacco-packets, signed with either her own, or one of her three servant maids' names.

They never believed the Bolsheviks would be able to keep the power they had taken, and failed to notice how the latter, having stolen their slogans, started to use them with ingenuity, speaking of 'land for peasants', 'peace for everybody', 'the Assembly reinstated', republic, freedom and all that...[15]Gippius saw the October Revolution as the end of Russia and the coming of the Kingdom of Antichrist.

In late 1919, invited to join a group of 'red professors' in Crimea, Gippius chose not to, having heard of massacres orchestrated by local chiefs Béla Kun and Rosalia Zemlyachka.

Having obtained permission to leave the city (the pretext being that they would head for the frontlines, with lectures on Ancient Egypt for Red Army fighters), Merezhkovsky and Gippius, as well as her secretary Vladimir Zlobin and Dmitry Filosofov, departed to Poland by train.

[18][19] In the early 1920s several of Gippius's earlier works were re-issued in the West, including the collection of stories Heavenly Words (Небесные слова, 1921, Paris) and the Poems.

[20] Encouraged by the success of Merezhkovsky's Da Vinci series of lectures and Benito Mussolini's benevolence, in 1933 the couple moved to Italy where they stayed for about three years, visiting Paris only occasionally.

[22] Regardless of whether or not the 1944 text of Merezhkovsky's allegedly pro-Hitler "Radio speech" was indeed a prefabricated montage (as his biographer Zobnin asserted), there was little doubt that the couple, having become too close to (and financially dependent on) the Germans in Paris, had lost respect and credibility as far as their compatriots were concerned, many of whom expressed outright hatred toward them.

Having defined the world of poetry as a three-dimensional structure involving "Love and Eternity meeting in Death", she discovered and explored in it her own brand of ethic and aesthetic minimalism.

Symbolist writers were the first to praise her 'hint and pause' metaphor technique, as well as the art of "extracting sonorous chords out of silent pianos," according to Innokenty Annensky, who saw the book as the artistic peak of "Russia's 15 years of modernism" and argued that "not a single man would ever be able to dress abstractions in clothes of such charm [as this woman]."

[7] Anton Krainy, Gippius's alter ego, was a highly respected and somewhat feared literary critic whose articles regularly appeared in Novy Put, Vesy and Russkaya Mysl.

1903-1909 garnered good reviews; Bunin called Gippius's poetry 'electric', pointing at the peculiar use of oxymoron as an electrifying force in the author's hermetic, impassive world.

Her lively, sharp thought, dressed in emotional complexity, sort of rushes out of her poems, looking for spiritual wholesomeness and ideal harmony," modern scholar Vitaly Orlov said.

[10] Gippius's novels The Devil's Doll (1911) and Roman Tzarevich (1912), aiming to "lay bare the roots of Russian reactionary ideas," were unsuccessful: critics found them tendentious and artistically inferior.

Well constructed, full of intriguing ideas, never short of insight, her stories and novellas are always a bit too preposterous, stiff and uninspired, showing little knowledge of real life.

While Blok (the man whom she famously refused her hand in 1918) saw the Revolution as a 'purifying storm', Gippius was appalled by the 'suffocating dourness' of the whole thing, seeing it as one huge monstrosity "leaving one with just one wish: to go blind and deaf."

Yet, as a modern Russian critic has put it, "Gippius's legacy, for all its inner drama and antinomy, its passionate, forceful longing for the unfathomable, has always borne the ray of hope, the fiery, unquenchable belief in a higher truth and the ultimate harmony crowning a person's destiny.