Zionism

[4] Zionism initially emerged in Central and Eastern Europe as a secular nationalist movement in the late 19th century, in reaction to newer waves of antisemitism and in response to the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment.

Specifically, prayers emphasized distinctiveness from other nations where a connection to Eretz Israel and the anticipation of restoration were based on messianic beliefs and religious practices, not modern nationalist conceptions.

[56][57][58] The concept of removing the non-Jewish population from Palestine was a notion that garnered support across the entire spectrum of Zionist groups, including its farthest left factions,[g][59] from early in the movement's development.

They believed that this concept would allow them to build a new framework for collective Jewish identity,[70] and thought that biology might provide "proof" for the "ethnonational myth of common descent" from the biblical land of Israel.

Another factor, according to Benny Morris, was the worry that that "employment of Arabs would lead to 'Arab values' being passed on to Zionist youth and nourish the colonists' tendency to exploit and abuse their workers", as well as security concerns.

[106] The transformation of a religious and primarily passive connection between Jews and Palestine into an active, secular, nationalist movement arose in the context of ideological developments within modern European nations in the 19th century.

[130] The conditions in Eastern Europe would eventually provide Zionism with a base of Jews seeking to overcome the challenges of external ostracism, from the Tsarist regime, and internal changes within the Jewish communities there.

They established the first two political parties, the socialist Po'alei Zion and the non-socialist Ha-Po'el Ha-Tza'ir and initiated the first collective agricultural settlements known as kibbutzim, which were fundamental in the formation of the Israeli state.

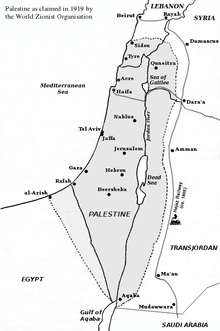

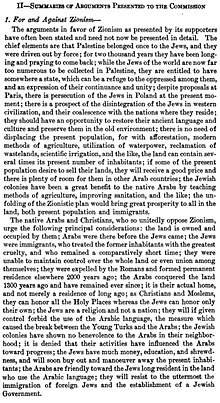

[166] In 1919, the US-based King–Crane Commission started with a strongly sympathetic disposition towards Zionism but concluded that the maximum Zionist demands implied subjection of Palestinians to Jewish rule and that this was a violation of the principle of self-determination, given the anti-Zionist sentiment of the non-Jewish population.

Jabotinsky rejected Weizmann's strategy of incremental state building, instead preferring to immediately declare sovereignty over the entire region, which extended to both the East and West bank of the Jordan river.

Instead, Britain committed only to establishing a Jewish national home "in Palestine" and promised to facilitate this without prejudicing the rights of existing "non-Jewish communities"—these qualifying statements aroused the concern of Zionist leaders at the time.

[182] As secretary general of the Histadrut and leader of the Zionist labor movement, Ben-Gurion adopted similar strategies and objectives as Weizmann during this period, disagreeing primarily on issues of specific tactical moves up until 1939.

[205] However, in his last book "The Jewish War Front" published in 1940, after the outbreak of WWII, Jabotinsky no longer ruled out the possibility of voluntary population transfer, though he still didn't view as a necessary solution.

[174] Later, Vladimir Jabotinsky, the right-wing Zionist leader, drew inspiration from the Nazi demographic policies which resulted in the expulsion of 1.5 million Poles and Jews, in whose place Germans resettled.

[211]By the time of the 1936 Arab revolt, almost all groups within the Zionist movement wanted a Jewish state in Palestine, "whether they declared their intent or preferred to camouflage it, whether or not they perceived it as a political instrument, whether they saw sovereign independence as the prime aim, or accorded priority to the task of social construction.

[z] The Irgun, the military arm of the revisionist Zionists, led by Menachem Begin, and the Stern Gang, which at one point sought an alliance with the Nazis,[232] would lead a series of terrorist attacks against the British starting in 1944.

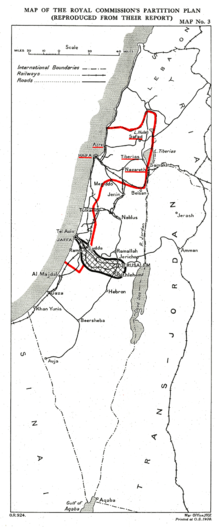

American lobbying efforts, pressuring UN delegates with the threat of withdrawal of US aid, eventually secured the General Assembly votes in favor of the partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states which was passed 29 November 1947.

[aa][clarification needed] The ensuing war led to the establishment of the State of Israel on 78% of Mandatory Palestine, instead of the 55% outlined in the UN partition plan, and resulted in the destruction of much of Palestinian society and the Arab landscape.

Masalha writes that it is not clear who the Yishuv was declaring independence from, as it was neither from the British colonial rule, which facilitated Jewish settlement against Palestinian wishes, nor from the land's indigenous inhabitants, who had long cultivated and owned it.

[255] However, the war and the Israeli conquest of the West Bank, invigorated and popularized a religious Zionist ideology associated with the Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and the Mercaz HaRav yeshiva, which believes that Zionism is a part of the historical process that will bring about the messianic age.

[158][page needed] From the turn of the century until the Arab revolt of 1936, there was room for political flexibility within the Zionist movement, many scholars argue that different currents of Zionism have had a shared core framework.

[34][261] Most mainstream histories of the movement delineate a few key strains, many following a taxonomy introduced during the period starting in the late 19th century and continuing into the 1930s: political, practical, socialist, cultural and revisionist.

[citation needed] In Labor Zionist thought, a revolution of the Jewish soul and society was believed necessary and achievable in part by Jews moving to Israel and becoming farmers, workers, and soldiers in a country of their own.

[293][294] Liberal Zionism, although not associated with any single party in modern Israel, remains a strong trend in Israeli politics advocating free market principles, democracy and adherence to human rights.

It is marked by a concern for democratic values and human rights, freedom to criticize government policies without accusations of disloyalty, and rejection of excessive religious influence in public life.

[269] Brit Shalom, which promoted Arab-Jewish cooperation, was established in 1925 by supporters of Ahad Ha'am's Spiritual Zionism, including Martin Buber, Gershom Scholem, Hans Kohn, "and other important figures of the intellectual elite of the pre-independence yishuv,[269] Gorny describes it as an ultimately marginal group.

As a result, Christian Zionists have significantly contributed politically and financially to Israeli nationalist forces, with the understanding that Israel's role is to facilitate the Second Coming of Christ and the elimination of Judaism.

[330][331] Today, opponents include Palestinian nationalists, several states of the Arab League and in the Muslim world, much of the left, and some secular Jews,[332][non-primary source needed] as well as the Satmar[333][334][335] and Neturei Karta[336] Jewish sects.

A human rights forum arranged in connection with the conference, on the other hand, did equate Zionism with racism and censured Israel for what it called "racist crimes, including acts of genocide and ethnic cleansing".

[382][383] Morris describes this relationship: These Jews were not colonists in the usual sense of sons or agents of an imperial mother country, projecting its power beyond the seas and exploiting Third World natural resources.