Zurvanism

As cited in Damascius's Difficulties and Solutions of First Principles (6th century CE), Eudemus describes a sect of the Medes that considered Space/Time to be the primordial "father" of the rivals Oromasdes "of light" and Arimanius "of darkness".

Robert Charles Zaehner proposed that this is because the individual Sasanian monarchs were not always Zurvanite and that Mazdean Zoroastrianism just happened to have the upper hand during the crucial period that the canon was finally written down.

In Yasna 72.10 Zurvan is invoked in the company of Space and Air (Vata-Vayu) and in Yasht 13.56, the plants grow in the manner Time has ordained according to the will of Ahura Mazda and the Amesha Spentas.

Certain however is that by the Sasanian Empire (226–651), the divinity "Infinite Time" was well established, and – as inferred from a Manichaean text presented to Shapur I, in which the name Zurvan was adopted for Manichaeism's primordial "Father of Greatness" [citation needed] – enjoyed royal patronage.

It was during the reign of Sasanian Emperor Shapur I (241–272 CE) that Zurvanism appears to have developed as a cult and it was presumably in this period that Greek and Indic concepts were introduced to Zurvanite Zoroastrianism.

That Mazdaism and Zurvanism competed for attention has been inferred from the works of Christian and Manichaean polemicists, but the doctrinal incompatibilities were not so extreme "that they could not be reconciled under the broad aegis of an imperial church".

The former continued to exist but in an increasingly reduced state, and by the 10th century the remaining Zoroastrians appear to have more closely followed the orthodoxy as found in the Pahlavi books (see also § The legacy of Zurvanism below).

As reasonable as it might have appeared from a purely intellectual point of view, such an absolute dualism had neither the appeal of a real monotheism nor any mystical element with which to nourish its inner life.

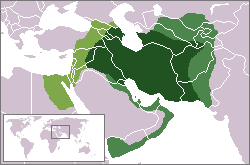

Following the fall of the Persian Empire, the south and west were relatively quickly assimilated under the banner of Islam, while the north and east remained independent for some time before these regions too were absorbed.

"Classical Zurvanism" is a term coined by Zaehner[3]: intro to denote the movement to explain the inconsistency of Zoroaster's description of the "twin spirits" as they appear in Yasna 30.3–5 of the Avesta.

According to Zaehner, this "Zurvanism proper" was genuinely Iranian and Zoroastrian in that it sought to clarify the enigma of the twin spirits that Zoroaster left unsolved.

Corroborated by Anquetil-Duperron's "erroneous rendering" of Vendidad 19.9, these led to the late 18th-century century conclusion that Infinite Time was the first Principle of Zoroastrianism and Ohrmuzd was therefore only "the derivative and secondary character".

[5]: 490–492 [13]: 687 According to Zaehner,[3][12] the doctrine of the cult of Zurvan appears to have three schools of thought, each to a different degree influenced by alien philosophies, which he calls These are described in the following subsections.

This challenge was a patently alien idea, discarding core Zoroastrian tenets in favor of the position that the spiritual world – including heaven and hell, reward and punishment – did not exist.

Even this is not necessarily a violation of orthodox Zoroastrian tradition, since the divinity Vayu is present in the middle space between Ormuzd and Ahriman, the void separating the kingdoms of light and darkness.

[8] Nonetheless, there is a semblance of Zurvanite elements in Vedic texts, and, as Zaehner puts it, "Time, for the Indians, is the raw material, the materia prima of all contingent being."

[citation needed] The pessimism evident in fatalistic Zurvanism existed in stark contradiction to the positive moral force of Mazdaism, and was a direct violation of one of Zoroaster's great contributions to religious philosophy: his uncompromising doctrine of free will.

The fall of the Achaemenian Empire, however, must have been disastrous for the Zoroastrian religion, and the fact that the Magi were able to retain as much as they did and restore it in a form that was not too strikingly different from the Prophet's original message after the lapse of some 600 years proves their devotion to his memory.

[12][page needed] Thus – according to Zaehner – while the direction that the Sasanians took was not altogether at odds with the spirit of the Gathas, the extreme dualism that accompanied a divinity that was remote and inaccessible made the faith less than attractive.

Writing in the historical present, he notes that "under Chosrau II (r. 590–628) and his successors, all kinds of superstitions tend to overwhelm the Mazdean religion, which gradually disintegrates, thus preparing the triumph of Islam."

[3]: 241 Thus, according to Zaehner and Duchesne-Guillemin, Zurvanism's pessimistic fatalism was a formative influence on the Iranian psyche, paving the way (as it were) for the rapid adoption of Shi'a philosophy during the Safavid era.

[17]: 587–588 A surviving Zurvanist myth describes him as "both male and female" and the one "god of time" who existed before all other things and gave birth to Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu.