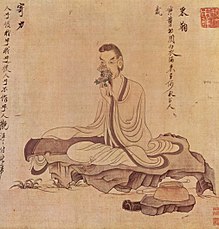

Guqin

[citation needed] The guqin is a very quiet instrument, with a range of about four octaves, and its open strings are tuned in the bass register.

[4] Legend has it that the qin, the most revered of all Chinese musical instruments, has a history of about 5,000 years, and that the legendary figures of China's pre-history – Fuxi, Shennong and Huang Di, the "Yellow Emperor" – were involved in its creation.

During the performance of qin, musicians may use a variety of techniques to reach the full expressing potential of the instrument.

There are many special tablatures that had developed over the centuries specifically dedicated to qin for their reference and a repertoire of popular and ancient tunes for their choice.

Important scale notes, called hui (徽), are marked by 13 glossy white dots made of mica or seashell inset in the front surface of the qin, occur at integer divisions of the string length.

The "crystal concordant" (perfectly harmonic) overtones can only be evoked by tapping the strings precisely at these hui.

According to the book Cunjian Guqin Zhifa Puzi Jilan, there are around 1,070 different finger techniques used for the qin.

An earlier form of music notation from the Tang era survives in just one manuscript, dated to the seventh century CE, called Jieshi Diao Youlan[26] (Solitary Orchid in Stone Tablet Mode).

It was so successful that from the Ming dynasty onwards, a great many qinpu (琴譜) (qin tablature collections) appeared, the most famous and useful being "Shenqi Mipu" (The Mysterious and Marvellous Tablature) compiled by Zhu Quan, the 17th son of the founder of the Ming dynasty.

Other famous pieces include "Liu Shui"[13] (Flowing Water), "Yangguan San Die"[32] (Three Refrains on the Yang Pass Theme), "Meihua San Nong"[33] (Three Variations on the Plum Blossom Theme), "Xiao Xiang Shui Yun"[34] (Mist and Clouds over the Xiao and Xiang Rivers), and "Pingsha Luo Yan"[35] (Wild Geese Descending on the Sandbank).

Therefore, it could be said that it really does require three months or years to finish dapu of a piece in order for them to play it to a very high standard.

Throughout the history of the qinpu, we see many attempts to indicate this rhythm more explicitly, involving devices like dots to make beats.

Probably, one of the major projects to regulate the rhythm to a large scale was the compilers of the Qinxue Congshu tablature collection of the 1910s to 1930s.

Traditionally, the sound board was made of Chinese parasol wood firmiana simplex, its rounded shape symbolising the heavens.

An antique guqin's age can be determined by this snake like crack pattern called "duanwen" (斷紋).

According to tradition, the qin originally had five strings, representing the five elements of metal, wood, water, fire and earth.

His successor, Zhou Wu Wang, added a seventh string to motivate his troops into battle with the Shang.

The twisted cord of strings is then wrapped around a frame and immersed in a vat of liquid composed of a special mixture of natural glue that binds the strands together.

The first is taigu[41] [Great Antiquity] which is the standard gauge, the zhongqing[42] [Middle Clarity] is thinner, whilst the jiazhong[43] [Added Thickness] is thicker.

Many traditionalists feel that the sound of the fingers of the left hand sliding on the strings to be a distinctive feature of qin music.

The modern nylon-wrapped metal strings were very smooth in the past, but are now slightly modified in order to capture these sliding sounds.

The most common tuning, "zheng diao" 〈正調〉, is pentatonic: 5 6 1 2 3 5 6 (which can be also played as 1 2 4 5 6 1 2) in the traditional Chinese number system or jianpu[53] (i.e. 1=do, 2=re, etc.).

In old times, the se (a long zither with movable bridges and 25 strings) was frequently used in duets with the qin.

Lately there has been a trend to use other instruments to accompany the qin, such as the xun (ceramic ocarina), pipa (four-stringed pear-shaped lute), dizi (transverse bamboo flute), and others for more experimental purposes.

In order fully to appreciate qin songs, one needs to become accustomed to the eccentric singing style adopted by certain players of the instrument, such as Zha Fuxi.

Being an instrument associated with scholars, the guqin was also played in a ritual context, especially in yayue in China, and aak in Korea.

The National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts continues to perform Munmyo jeryeak (Confucian ritual music), using the last two surviving aak melodies from the importation of yayue from the Song dynasty emperor Huizong in 1116, including in the ensemble the seul (se) and geum (금; qin).

Actors often possess limited knowledge on how to play the instrument and instead, they mime it to a pre-recorded piece by a Qin player.

[61] The qin was also featured in the 2008 Summer Olympics Opening Ceremony in Beijing, played by Chen Leiji (陳雷激).

Behind-the-scenes footage of the production of the series revealed that several actors were given qin lessons prior to filming to prepare them for their roles as characters that played the instrument.