1721 Boston smallpox outbreak

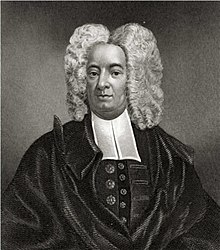

[4][3] The outbreak motivated Puritan minister Cotton Mather and physician Zabdiel Boylston to variolate hundreds of Bostonians as part of the Thirteen Colonies' earliest experiment with public inoculation.

The outbreak also altered social and religious public discourse about disease, as Boston's newspapers published various pamphlets opposing and supporting the inoculation efforts.

On 22 April 1721 the British passenger ship HMS Seahorse arrived at Boston from Barbados,[6] after one stop at Tortuga,[7] with a crew of sailors who had just survived smallpox.

[8] Boston's water bailiff inspected Seahorse and discovered another two or three cases of smallpox in various stages before ordering the ship to leave the harbor.

[10] James Franklin's The New England Courant was founded in August amid the outbreak and the issue of smallpox and preservation from it became front page news.

Cotton Mather sent letters to Boston's 14 other physicians regarding the outbreak[1] imploring them to wage a medical campaign against smallpox by inoculating their own patients or volunteers.

[13] Mather read physician Emmanuel Timoni's description of a similar procedure witnessed while serving Great Britain's ambassador in Turkey.

[14][5] The procedure Timoni called inoculation involved drying pus from a smallpox patient and rubbing or scraping it into a healthy person's skin, giving them a mild case of pox that conferred lifetime immunity.

Cotton Mather writes in a letter detailing Dr. Boylston's work in Boston: "The experiment has now been made on several hundred persons, upon both male and female, upon both old and young, upon both strong and weak, upon both white and black.

"[17] Boylston was unable to continue his inoculation campaign beyond November due to opposition from Boston's Selectmen restricting him, as well as occasional violence from the public.

One pamphlet published in The New England Courant read "Some have been carrying about instruments of inoculation, and bottles of poisonous humor, to infect all who were willing to submit to it.

Despite the opposition, Boylston garnered support of local learned men like Cotton's father Increase Mather and four other "inoculation ministers" by the names of Benjamin Coleman, Thomas Prince, John Webb, and William Cooper.

[4] The device failed to explode, but a note tied to it read "Cotton Mather, I was once of your meeting, but the cursed lye you told of - you know who, made me leave you, you dog, and damn you, I will inoculate you with this, with a pox on you!

[1] The New England Courant, under the leadership of its new editor 16 year-old Benjamin Franklin, continued to publish satirical articles about the Mather and inoculation in the months following the epidemic.

Most of Boston's clergy seemed to have supported inoculation, and some wrote an op-ed opposing Williams and Douglass's criticism: "tho [Dr. Boylston] has not had... an Academic Education, and congruently not the Letters of some Physicians in town, yet he ought by no means be called Illiterate, Ignorant, etc.

[2] Boylston's successful experiments on students and faculty at Harvard led to early acceptance in Boston's powerful academic community for the procedure.