Vaccination

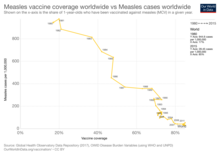

Early success brought widespread acceptance, and mass vaccination campaigns have greatly reduced the incidence of many diseases in numerous geographic regions.

Vaccination is treatment of an individual with an attenuated (i.e. less virulent) pathogen or other immunogen, whereas inoculation, also called variolation in the context of smallpox prophylaxis, is treatment with unattenuated variola virus taken from a pustule or scab of a smallpox patient into the superficial layers of the skin, commonly the upper arm.

Other vaccines, including those for COVID-19, help to (temporarily) lower the chance of severe disease for individuals, without necessarily reducing the probability of becoming infected.

[38][40] During the next round of testing, researchers study vaccines in animals, including mice, rabbits, guinea pigs, and monkeys.

[43] In a response to the narcolepsy reports following immunization with Pandemrix, the CDC carried out a population-based study and found the FDA-approved 2009 H1N1 flu shots were not associated with an increased risk for the neurological disorder.

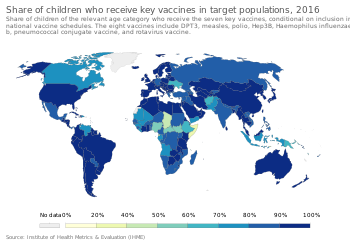

[65] In 2024, a WHO/UNICEF report found “the number of children who received three doses of the vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP) in 2023 – a key marker for global immunization coverage – stalled at 84% (108 million).

More than half of unvaccinated children live in the 31 countries with fragile, conflict-affected and vulnerable settings.”[66] Vaccines have led to major decreases in the prevalence of infectious diseases in the United States.

[67] Vaccination adoption is reduced among some populations, such as those with low incomes, people with limited access to health care, and members of certain racial and ethnic minorities.

Distrust of health-care providers, language barriers, and misleading or false information also contribute to lower adoption, as does anti-vaccine activism.

[68] Most government and private health insurance plans cover recommended vaccines at no charge when received by providers in their networks.

[70][71] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) publishes uniform national vaccine recommendations and immunization schedules, although state and local governments, as well as nongovernmental organizations, may have their own policies.

In 1796, Edward Jenner, a doctor in Berkeley in Gloucestershire, England, tested a common theory that a person who had contracted cowpox would be immune from smallpox.

Early attempts at confirmation were confounded by contamination with smallpox, but despite controversy within the medical profession and religious opposition to the use of animal material, by 1801 his report was translated into six languages and over 100,000 people were vaccinated.

[81] In the same year Scott penned a letter to the editor in the Bombay Courier, declaring that "We have it now in our power to communicate the benefits of this important discovery to every part of India, perhaps to China and the whole eastern world".

[86]: 115–116 In 1974 the WHO adopted the goal of universal vaccination by 1990 to protect children against six preventable infectious diseases: measles, poliomyelitis, diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, and tuberculosis.

[86]: 120 Despite decades of mass vaccination polio remains a threat in India, Nigeria, Somalia, Niger, Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Indonesia.

By 2006 global health experts concluded that the eradication of polio was only possible if the supply of drinking water and sanitation facilities were improved in slums.

[86]: 124 The deployment of a combined DPT vaccine against diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough), and tetanus in the 1950s was considered a major advancement for public health.

[88] To eliminate the risk of outbreaks of some diseases, at various times governments and other institutions have employed policies requiring vaccination for all people.

For example, an 1853 law required universal vaccination against smallpox in England and Wales, with fines levied on people who did not comply.

[90] Beginning with early vaccination in the nineteenth century, these policies were resisted by a variety of groups, collectively called antivaccinationists, who object on scientific, ethical, political, medical safety, religious, and other grounds.

[95] Public Health Law Research, an independent US based organization, reported in 2009 that there is insufficient evidence to assess the effectiveness of requiring vaccinations as a condition for specified jobs as a means of reducing incidence of specific diseases among particularly vulnerable populations;[96] that there is sufficient evidence supporting the effectiveness of requiring vaccinations as a condition for attending child care facilities and schools;[97] and that there is strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of standing orders, which allow healthcare workers without prescription authority to administer vaccine as a public health intervention.

Some families have won substantial awards from sympathetic juries, even though most public health officials have said that the claims of injuries were unfounded.

[102] Some concerns from families might have arisen from social beliefs and norms that cause them to mistrust or refuse vaccinations, contributing to this discrepancy in side effects that were unfounded.

[92] It is widely accepted that the benefits of preventing serious illness and death from infectious diseases greatly outweigh the risks of rare serious adverse effects following immunization.

[113] In 2011, Andrew Wakefield, a leading proponent of the theory that MMR vaccine causes autism, was found to have been financially motivated to falsify research data and was subsequently stripped of his medical license.

[117][118] The notion of a connection between vaccines and autism originated in a 1998 paper published in The Lancet whose lead author was the physician Andrew Wakefield.

[119] In 2004, 10 of the original 12 co-authors (not including Wakefield) published a retraction of the article and stated the following: "We wish to make it clear that in this paper no causal link was established between MMR vaccine and autism as the data were insufficient.

Although vaccinations usually induce long-term economic benefits, many governments struggle to pay the high short-term costs associated with labor and production.

[128] According to a 2021 paper, vaccinations against haemophilus influenzae type b, hepatitis B, human papillomavirus, Japanese encephalitis, measles, neisseria meningitidis serogroup A, rotavirus, rubella, streptococcus pneumoniae, and yellow fever have prevented an estimated 50 million deaths from 2000 to 2019.