1755 Lisbon earthquake

Contemporary reports state that the earthquake lasted from three and a half to six minutes, causing fissures 5 metres (16 ft) wide in the city center.

Survivors rushed to the open space of the docks for safety and watched as the sea receded, revealing a plain of mud littered with lost cargo and shipwrecks.

Other towns in different Portuguese regions, such as Peniche, Cascais, Setúbal and even Covilhã (which is located near the Serra da Estrela mountain range in central inland Portugal) were visibly affected by the earthquake, the tsunami, or both.

The shock waves of the earthquake destroyed part of Covilhã's castle walls and its large towers and damaged several other buildings in Cova da Beira,[9][10] as well as in Salamanca, Spain.

Places such as Ceuta (ceded by Portugal to Spain in 1668) and Mazagon, where the tsunami hit hard the coastal fortifications of both towns, in some cases going over it, and flooding the harbor area, were affected.

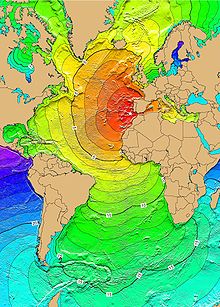

[15] Although seismologists and geologists have always agreed that the epicenter was in the Atlantic to the west of the Iberian Peninsula, its exact location has been a subject of considerable debate.

Early hypotheses had proposed the Gorringe Ridge, about 320 km (170 nmi; 200 mi) south-west of Lisbon, until simulations showed that a location closer to the shore of Portugal was required to comply with the observed effects of the tsunami.

[16] Pereira estimated the total death toll in Portugal, Spain and Morocco from the earthquake and the resulting fires and tsunami at 40,000 to 50,000 people.

[17] Eighty-five percent of Lisbon's buildings were destroyed, including famous palaces and libraries, as well as most examples of Portugal's distinctive 16th-century Manueline architecture.

The Royal Ribeira Palace, which stood just beside the Tagus river in the modern square Praça do Comércio, was destroyed by the earthquake and tsunami.

After the catastrophe, Joseph I developed a fear of living within walls, and the court was accommodated in a huge complex of tents and pavilions in the hills of Ajuda, then on the outskirts of Lisbon.

The king's claustrophobia never waned, and it was only after Joseph's death that his daughter Maria I of Portugal began building the royal Ajuda Palace, which still stands on the site of the old tented camp.

When asked what was to be done, Pombal reportedly replied "bury the dead and heal the living",[20] and set about organizing relief and rehabilitation efforts.

Firefighters were sent to extinguish the raging flames, and teams of workers and ordinary citizens were ordered to remove the thousands of corpses before disease could spread.

On 4 December 1755, a little more than a month after the earthquake, Manuel da Maia, chief engineer to the realm, presented his plans for the re-building of Lisbon.

Keen to have a new and perfectly ordered city, the king commissioned the construction of big squares, rectilinear, large avenues and widened streets – the new mottos of Lisbon.

The noted writer-philosopher Voltaire used the earthquake in Candide and in his Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne ("Poem on the Lisbon disaster").

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was also influenced by the devastation following the earthquake, the severity of which he believed was due to too many people living within the close quarters of the city.

Kant's theory, which involved shifts in huge caverns filled with hot gases, though inaccurate, was one of the first systematic attempts to explain earthquakes in natural rather than supernatural terms.

Werner Hamacher has claimed that the consequences of the earthquake extended into the vocabulary of philosophy, making the common metaphor of firm "grounding" for philosophers' arguments shaky and uncertain: "Under the impression exerted by the Lisbon earthquake, which touched the European mind in one [of] its more sensitive epochs, the metaphor of ground and tremor completely lost their apparent innocence; they were no longer merely figures of speech" (263).

The prime minister, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal, was the favourite of the king, but the aristocracy despised him as an upstart son of a country squire.

Because Pombal was the first to attempt an objective scientific description of the broad causes and consequences of an earthquake, he is regarded as a forerunner of modern seismological scientists.

[31] A fictionalised version of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake features as a main plot element of the 2014 video game Assassin's Creed Rogue, developed and published by Ubisoft.

The Lisbon earthquake is vividly depicted in Avram Davidson's Masters of the Maze, one of the many times and places visited by the book's time-traveling protagonists.